Squid, octopus, and cuttlefish are booming: Good news from the sea?

Loading...

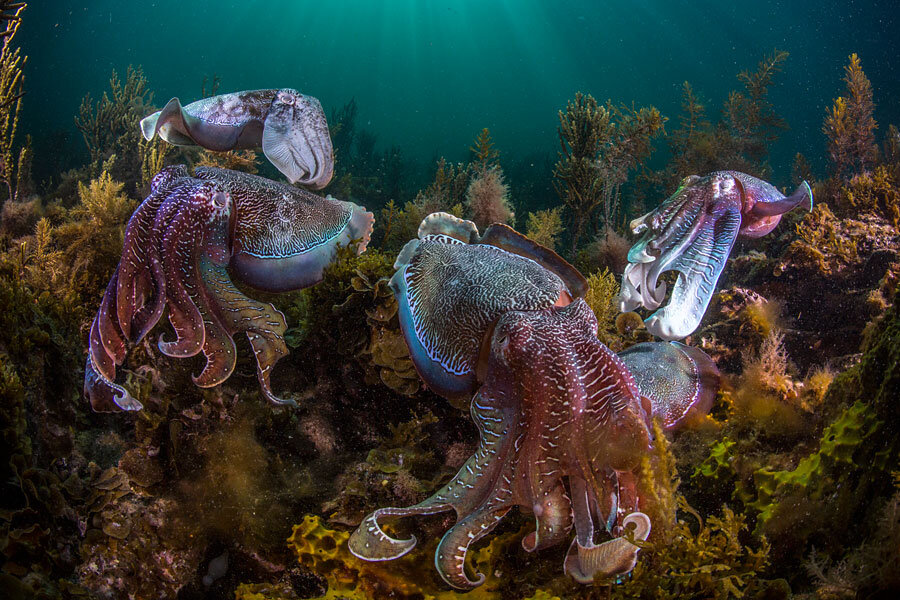

It's rare to hear about life doing well in the oceans these days. But cephalopods – a group of marine animals that includes squids, octopuses, and cuttlefish – are thriving.

And cephalopods aren't merely getting by. They've been on the rise for the past six decades, according to a study published Monday in the journal Current Biology.

"It is certainly nice to see something going up," study lead author Zoë Doubleday, a marine biologist at the University of Adelaide, tells The Christian Science Monitor.

But there could be a downside to such an abundance.

"From a squid's perspective, it is good news," says Michael Vecchione, director of the NOAA Fisheries National Systematics Laboratory and an invertebrate zoologist at the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History who was not part of the new study. But "maybe not from a fish's perspective."

Cephalopods "are really voracious predators," Dr. Vecchione explains to the Monitor. "They have a high metabolic rate, high growth rate and as a result they have a high requirement for food. So they eat a lot of stuff. If there are a lot of squids out there eating juvenile fishes, it could make it more difficult for the fish populations to recover."

But cephalopods aren't just big eaters. They're also food sources for many larger marine animals, birds, and humans, Dr. Doubleday says. And, she says, balance might return to the food chain over time.

"Nature has a way of self-regulating," Doubleday says. Perhaps this growing population will hit a point when there isn't enough food to support such an abundance. And, "they're highly cannibalistic," she says, "so they might self-regulate by eating each other. That often happens when food is limited."

"They might crash just as much as they've increased," Doubleday says.

Why so many cephalopods?

Cephalopods are often called "weeds of the sea," Doubleday says. "Like the weeds in your garden, they're the first things that respond to change or disturbance."

These animals grow quickly, have short lifespans, and can adapt quickly to new environmental conditions, she explains. And those attributes likely come together to make it easier for cephalopods to thrive in the changing oceans.

But what exactly those changing conditions are is still a question.

Perhaps overfishing, changing water temperatures, or other effects of climate change are opening doors for cephalopod population growth. "There's probably multiple causes that are interrelated," Vecchione says.

Doubleday says her team is currently looking into what those causes might be.

To assess the state of cephalopods, Doubleday and her colleagues pored over data from fisheries and other oceanic surveys.

"They've provided some pretty convincing evidence that cephalopod populations have increased," Vecchione says. But he warns that these methods overlook those species that humans don't regularly come into contact with, like the animals living deep in the sea instead of along coasts or in shallower waters.

"There's still a lot of unanswered questions," he says.

Cephalopods or canaries?

The rise in cephalopods may not just be bad news for the fish they eat.

Because cephalopods are particularly sensitive to changes in the ocean, they could be like the proverbial canary in a coal mine, Doubleday says. "If we're seeing these changes in the cephalopods, it means something might be changing in the ocean."

"We're seeing a new world here, one we haven't seen before. Any time you push an ecosystem into a different state, there's greater uncertainty in how it will behave, and how it will respond to future changes. Frankly, I think that should make people really worried," Ben Halpern, a biology professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara's Bren School of Environmental Science and Management and director of the school's Center for Marine Assessment and Planning tells the Monitor in an email.

"More squid and octopus to eat may seem like a good thing, and in the short run maybe it is. But I'm more worried about the long run," says Dr. Halpern, who was not part of the study.