How was the right eye of the 'Man in the Moon' made?

Where did the "Man in the Moon" come from, that fabled face that stares down at us from the lunar surface?

We may not have all the answers, but new research has at least shed some light on one of the eyes – his right one, to be exact. Or, the left one, if you're a stargazer staring up from Earth.

Either way, the scientific name of the crater in question is the Imbrium Basin, and the new research, published Wednesday in Nature, suggests the asteroid that sculpted it was far bigger than previously thought. This shift in thinking provides fresh insight not only into the formation of the moon’s scarred surface, but also a better understanding of the impacts that afflicted other planets in the solar system, including Earth.

“We show that Imbrium was likely formed by an absolutely enormous object, large enough to be classified as a protoplanet,” said lead author Pete Schultz, professor of Earth, environmental, and planetary sciences at Brown University, Providence, R.I.. “This is the first estimate for the Imbrium impactor’s size that is based largely on the geological features we see on the Moon.”

That protoplanet, which the researchers estimate to have been 150 miles in diameter, would have barreled into the moon at 22,000 miles per hour, striking at an angle of 30 degrees with such force that it left scars in the moon’s surface up to 300 miles long.

Previous estimates granted the asteroid a diameter of only 50 miles, but those studies were based solely on computer models.

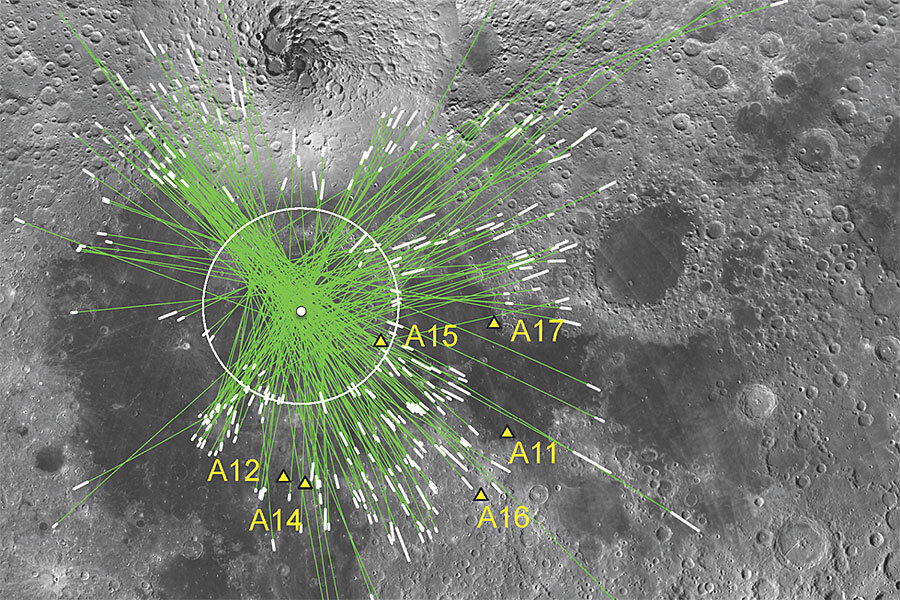

Dr. Schultz and his colleagues considered something else: the Imbrium Sculpture, a mosaic of grooves spilling out of the crater and onto the moonscape beyond. Some of these have always made sense, spreading out in a radial pattern, the likely legacy of chunks of moon rock scattered by the impact. Others, however, have long perplexed astronomers, not fitting into any easy explanation.

“The sculpturing has been known for well over 100 years,” Schultz told The Guardian. “The mystery has been why didn’t the grooves all come from the centre of the basin?”

To dig into these inconsistencies, Schultz employed the assistance of NASA’s Ames Vertical Gun Range, a facility that boasts a 14-foot cannon capable of shooting projectiles up to 16,000 m.p.h., slamming them into impact plates and recording the ballistic dynamics on high-speed cameras.

What the researchers found was that with low-angle impacts, the incoming objects would often begin to break apart before the final crater was gouged from the recipient’s surface. The fragments that tore from the main body would continue to travel at high velocity, and they would carve gashes in the plate’s surface prior to the main depression.

Using this fresh insight, the scientists were able to calculate the new, more dramatic estimates for the size of the asteroid responsible for the Man in the Moon's eye.

But the implications go further.

"At that time, the Moon would have been much closer [to the Earth], only half of its present distance, if even that,” Schultz told the BBC. "So anything coming off the Moon would have covered us in lunar debris."

Moreover, the work offers further insight into the period in question, aptly termed the Late Heavy Bombardment, a tumultuous time in our solar system’s history, when Jupiter and Saturn were shifting into new positions, and asteroids were causing havoc.

It now appears that these hunks of space rock that were crashing into planets and carving new features included some that were far larger than previously believed.

“The Moon still holds clues that can affect our interpretation of the entire solar system,” said Schultz in a Brown University press release. “Its scarred face can tell us quite a lot about what was happening in our neighborhood 3.8 billion years ago.”