After many successes, comet hunter Philae will be missed

As the comet 67P moves farther from the Sun, the European Space Agency (ESA) is slowly shutting down its Rosetta mission, which launched in March of 2004 and arrived at the comet in August of 2014.

An early step of this process is shutting down Rosetta’s Electrical Support System Processor Unit, which is the interface it used to communicate with the lander, Philae, the ESA announced on its blog. This step will enable Rosetta to save energy to continue its operations over the next two months before it makes a crash landing into 67P on September 30.

"Considering how many different circumstances Philae had to be designed for, the lander functioned very well," Valentina Lommatsch, a member of the lander team at the German Aerospace Centre (DLR), told Nature. "No, we didn't get everything we hoped for, but I can't even list all the obstacles Philae overcame successfully."

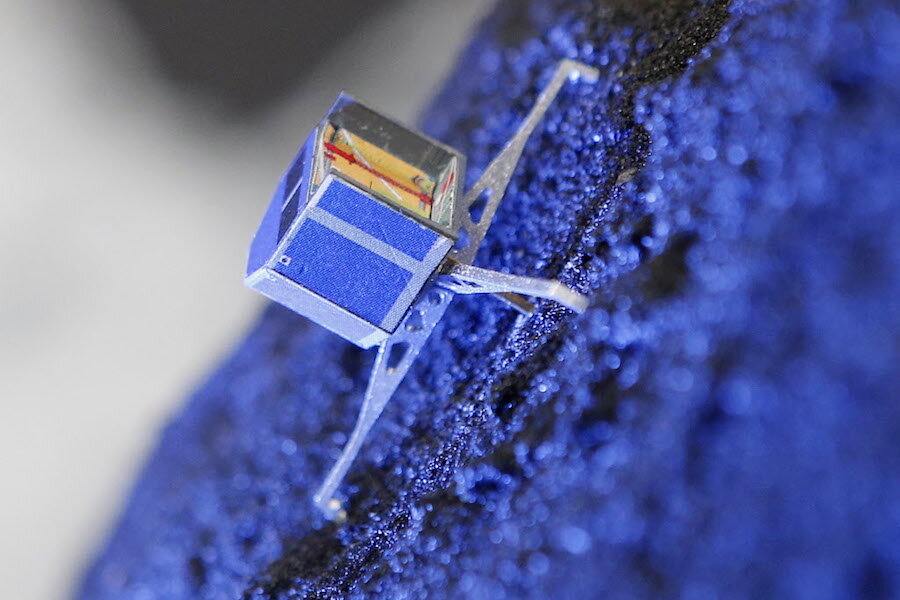

The Rosetta mission was launched to discover what secrets comets might hold about the origins of life, and the washing-machine-sized Philae was a large part of that operation.

“Comets are the most primitive bodies in the solar system. By studying that material, we learn about the chemistry of the early solar nebula,” Paul Weissman, Interdisciplinary Scientist for the Rosetta Mission at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, says in a video about the mission.

In its 64 hours of experiments, Philae found that 67P has no magnetic field, but does have sugar-like aldehydes that could be building blocks of life, and a hard crust covered with dust and ice, although not as much as expected.

“We found that the comet wasn’t as rich in ice as we thought it would be,” Essam Heggy, a co-investigator for the CONSERT instrument for the Rosetta Mission, says in the video.

The combination of ingredients like alcohols, sulfurs, and ice on comets could have enabled them to transport the building-blocks of life to Earth during high-impact collisions, says Dr. Heggy.

One way Philae gathered data for its discoveries was by detecting and analyzing volatile compounds near the comet's surface, according the Space Exploration Network's Paul Sutherland.

Philae was pre-programmed to carry out a number of experiments as soon as it landed at its designated site, Agilkia, on November 12, following a seven hour descent from the mothership. One was to “sniff the air” so that experiments COSAC (Cometary Sampling and Composition) and Ptolemy could determine the chemical make-up of the gas and dust being given off by the comet.

During its collection, Philae found 16 organic compounds, four of which were not previously found on comets.

“While this is a long, long way from finding life itself, the data show that the organic compounds that eventually translated into organisms here on Earth existed in the early Solar System,” UK comet expert Professor Monica Grady wrote for The Conversation.

While the public mourns the loss of Philae on social media, the real tragedy for the ESA will be letting go of Rosetta, which is still actively sending data, Stephan Ulamec, the Philae lander manager at the German Aerospace Centre, told Nature.