Our corner of the Milky Way might be bigger than previously thought

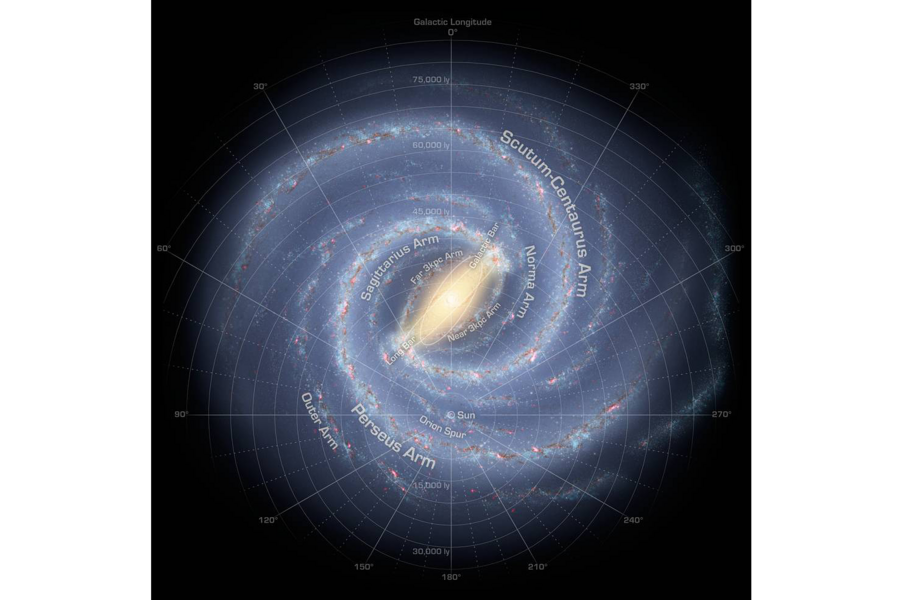

Some galaxies are near perfect spirals, with two or four arms starting at the center of the swirling stellar mass and entirely encircling it as the arms stretch outward. But not our galaxy. According to new research, the Milky Way galaxy is more of a patchwork spiral galaxy.

The evidence lies in our own galactic neighborhood. The section of the Milky Way that contains our solar system is actually a substantial spiral arm, not just a small spur as previously thought.

But the Local Arm, as our corner of the galaxy is called, does not fully encircle the galaxy as a perfect spiral arm would. Instead, it extends about 20,000 light-years around the galaxy, while some of the other arms extend five to six times that length, scientists report in a paper published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances.

And this means "our galaxy probably does not have one of these beautiful spiral patterns that we see in some external galaxies," University of Toronto astronomer Jo Bovy, who was not part of the research, tells The Christian Science Monitor in a phone interview.

This discovery is part of a larger project sharpening our view of the Milky Way.

It's not easy to map our own galaxy because, as Dr. Bovy points out, "we're sitting right in the middle of it."

From Earth, it's difficult to sort out where stars cluster and therefore what the structure of the Milky Way looks like.

"The fundamental problem for the Milky Way is that it's a disk-like system and we're inside the disk," Mark Reid, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., and co-author on the new study, tells the Monitor in a phone interview. "Let's say you have a disk," he explains, "and you paint a spiral pattern on the top of it. When you turn the disk sideways and look at it, you can't see that spiral pattern."

Furthermore, dust obscures a lot of visible starlight.

So Dr. Reid and his colleagues peered out into the galaxy at radio wavelengths. The team used the National Radio Astronomy Observatory's Very Long Baseline Array of telescopes to note where star-forming regions were in the sky. Then, they used a simple calculation to figure out how far away those celestial bodies were from Earth.

"We found that there are a lot of massive star-forming regions in the Local Arm," Reid says, "So the Local Arm appears to be a pretty major structure in our Milky Way."

The team had already reported that the Local Arm, also often called the Orion Spur, was more than just a spur off-shoot from a full-fledged galactic arm, but the new paper reports even more star-forming regions in the structure, refining the depiction of the structure to be an arm.

"The Local Arm and the associated Cygnus X region have always been the odd man out of Galactic structure," Thomas Steiman-Cameron, an astronomer at Indiana University, Bloomington, who was not part of the research, writes in an email to the Monitor. As such, the new research is a step toward being able to fit these oddballs into the overall context of our galaxy, he says.

Although the Local Arm may not be a spur anymore, Reid and his colleagues did find evidence of a true spur, a sort of galactic bridge between the Local Arm and the neighboring Sagittarius arm.

And that suggests the Milky Way's structure is a bit messier and more chaotic than the classic image of a spiral galaxy, Leo Blitz, professor emeritus of astronomy at the University of California at Berkeley who was not part of the research, tells the Monitor. It paints a picture of more complex galactic structures within spiral galaxies.

Using these same techniques, the researchers have been able to refine other details about the Milky Way. For example, Reid says, "we've been finding that the Milky Way's mass is bigger than people thought."

By their measurements and calculations, our galaxy is about 30 percent larger than previously thought, Reid says. And that brings it on par with our sister galaxy Andromeda.

Astronomers know a lot more about other galaxies like the Andromeda galaxy than the Milky Way galaxy because they can literally snap a photo of it using fancy Earth-based tools like NASA's Hubble Space Telescope. But to snap a selfie of our own galaxy would be a bigger ordeal.

If you could send a spacecraft out above the Milky Way, Reid explains, it would have to travel for about 100,000 years, snap the picture, and then send it back, "which, of course, would take about 10,000 years to transmit the signal." He adds, with a laugh, "But we're not that patient."