How did the European Space Agency's Mars lander meet its untimely end?

Just about a minute before it was supposed to touch down on Mars, Schiaparelli lost contact with mission control.

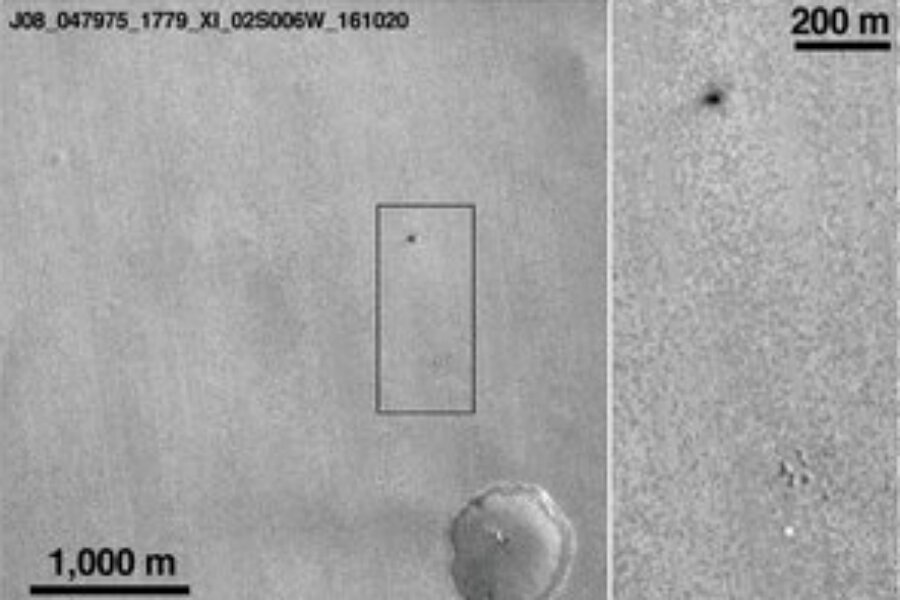

At first it was unclear what became of the craft, designed by the European Space Agency (ESA) and Russian space agency Roscosmos to demonstrate soft landing technologies on Mars. Then, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter obtained low-resolution photos that appeared to show a wreckage.

On Friday, ESA officials confirmed that the lander, which began its final descent about 2.5 miles above the surface, was likely lost.

“Schiaparelli reached the ground with a velocity that was much higher than it should have been, several hundred kilometers per hour, and was then unfortunately destroyed by the impact,” ExoMars Flight Director Michel Denis told Reuters.

Schiaparelli’s landing was anything but ‘soft’ – the spacecraft failed to fire its descent-slowing thrusters as long as intended, and full fuel tanks would have exploded upon impact.

ESA has not yet determined what caused the crash, but is currently analyzing the lander’s recovered descent data for clues. Officials say the craft's descent technology, designed to slow the lander down as it careened toward Mars, deployed normally.

The Christian Science Monitor’s Weston Williams reported earlier this month:

Essentially, Schiaparelli will be launched with a traditional heat shield and parachute combo, but the thin atmosphere will not be enough to slow the [Entry, Descent and Landing Demonstrator] down enough for a safe landing with those methods. Once the parachute slows the descent as much as it can, the hydrazine rockets will slow it the rest of the way before cutting out two meters from the surface. From there, the probe will drop, with a crushable layer protecting the rest of the probe from harm.

“But somehow the parachute was released a bit too early, and after that the engine functioned, but only for a few seconds, which was too little,” Denis said.

The crash may conjure up painful memories for ESA and spaceflight enthusiasts. In 2003, the agency’s Beagle 2 lander lost contact with mission control during its final descent. For twelve years, nobody knew what became of the craft. In 2015, NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter obtained new images of the landing site: Beagle 2 had touched down successfully, but eventually lost power after it failed to deploy two of its solar panels.

Other nations have experienced similar mishaps on the Red Planet. In 1998, NASA’s Mars Polar Lander slammed into the planet’s rocky surface after prematurely terminating its engine during final descent. More than two decades earlier, a design flaw in Russia’s Mars 6 lander prevented the return of any usable data from the craft’s entry.

In many ways, Schiaparelli’s mission was failure. Without a successful test landing, ESA’s 2020 Mars rover will have a lot less to go on. But officials still consider ExoMars a tentative success: the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) is still operational, sniffing out methane and other bio-significant gases on its orbit around the Red Planet.

This report includes material from Reuters.