Why more than 100 scientists are backing an asteroid-deflection mission

How do you stop an asteroid headed directly at Earth?

That's the question that scientists have been asking for decades now. For most of human history, the only answer to such a question would be a shrug. But as asteroid detection continues to improve, scientists say they might be able to have enough time between spotting an incoming meteor and its impact to actually keep it from hitting our planet.

While scientists believe that asteroids like the kind that wiped out the dinosaurs are rare, smaller asteroids can still cause massive damage all over the world. In order to prevent these destructive collisions, more than 100 scientists published a letter in support of a joint NASA/ESA mission, set to launch in 2020, to study and ultimately deflect an asteroid. The mission would enable humanity to learn more about the threat posed by near-Earth objects and would mark the first time an asteroid has been deflected away from Earth in a dry run for planetary defense against near-Earth objects on a more destructive course.

"Of the near-Earth objects (NEOs) so far discovered, there are more than 1700 asteroids currently considered hazardous. Unlike other natural disasters, this is one we know how to predict and potentially prevent with early discovery," reads the letter. "As such, it is crucial to our knowledge and understanding of asteroids to determine whether a kinetic impactor is able to deflect the orbit of such a small body, in case Earth is threatened."

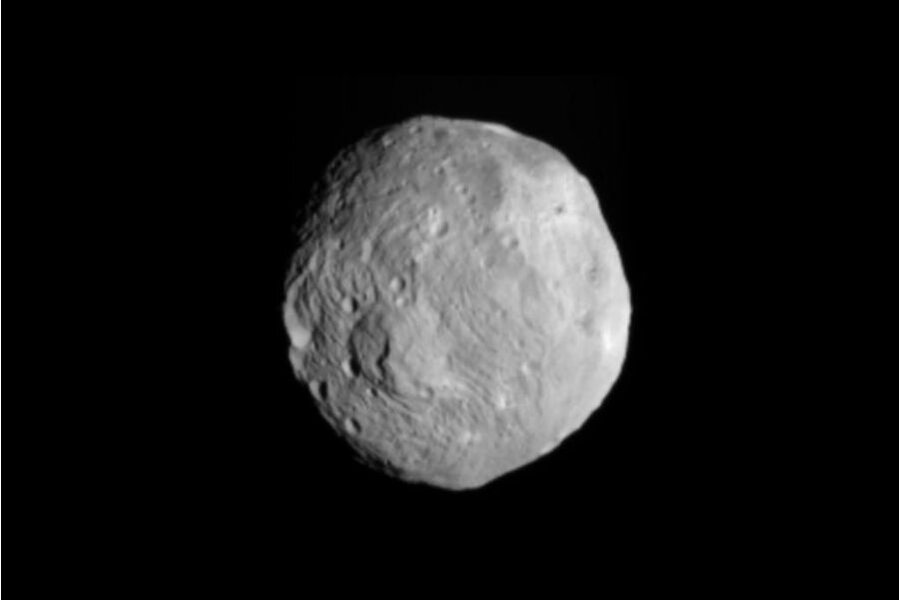

The letter, which can be signed by any concerned Earthling, describes the proposed 2-part AIDA mission to the binary asteroid system, Didymos and Didymoon. The first probe, ESA's Asteroid Impact Mission (AIM), will study the asteroids from orbit when it arrives in 2022. It will then be able to watch NASA's Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) as it collides with Didymoon about four months later, knocking it off course in a demonstration of technology that may one day save lives.

"We are really optimistic, because it is a very unique opportunity," Cornelius Schalinski, deputy head of business development for OHB, the German private space company charged with leading the implementation of AIM, told Space.com. "It has to go in 2020. Otherwise, the opportunity is lost. It is an asteroid that gets pretty close to Earth, so we can, with comparatively small cost and effort, test technologies that we need for future missions that are further away."

The timing of the AIDA mission is crucial, which is why the letter is important. In early December, ESA's council of ministers will meet to determine whether or not to provide funding for the mission.

Scientists have been abstractly concerned with the problem of an asteroid impact for over a century. But recently, that problem has become much more concrete, as the Christian Science Monitor's Joseph Dussault recently explained:

On the morning of June 30, 1908, a large meteor exploded in mid-air near Russia’s Stony Tunguska River. No casualties were reported, as the area was sparsely populated, but the so-called Tunguska event flattened nearly 800 square miles of forest. New York City, by comparison, is just over 300 square miles.

In 2013, a significantly smaller meteor – just 65 feet wide, compared to the 200-650 foot estimate of the Tunguska object – burst over Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia. The blast was around 30 times more powerful than the atomic bomb detonated at Hiroshima, and injured 1,500 people.

The Chelyabinsk meteor was a wake-up call for the world’s space agencies. Several had already initiated a number of “spaceguard” missions in the 1980s and 1990s, designed to track the orbits of near-Earth objects (NEOs) which might enter the atmosphere. In 1992, NASA even sponsored an “asteroid interception workshop” in New Mexico.

As scientists continue to discover more and more near-Earth objects, some of which could pose a threat to populations on Earth, the upcoming AIDA mission has the potential of acting as a safety net for human beings in the line of fire. But the mission would also have great scientific value as well, giving us important insights into the early history of planet formation in our own cosmic neighborhood.

"Asteroids are marvels of planetary systems, in particular our Solar System," the scientists point out in the AIDA letter. "Like comets, they are left over matter from the formation of planets, rich in minerals and rich in scientific knowledge of the early history of our Solar System."