How did scientists create the strongest artificial spider silk ever?

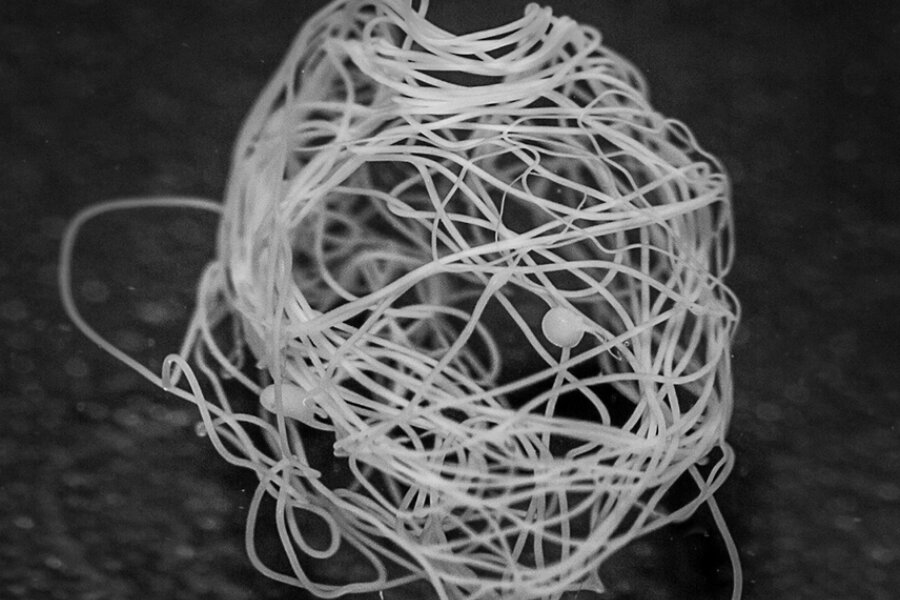

Peter Parker, eat your heart out. Scientists have announced a new technique for producing the strongest artificial spider silk yet.

Spider silk has long been the target of immense commercial interest because of its formidable strength and elasticity, but technical challenges stymie attempts to manufacture artificial threads as good as the real deal. Now, using a setup that takes cues from the natural process, a team of scientists has come closer than ever before, according to a paper published in the journal Nature on Monday.

Nature’s weavers produce impressively high quality goods. Spider silk is the strongest known fiber on the planet, even beating out steel and Kevlar ounce per ounce. Despite its superlative strength, it also maintains great elasticity, capable of stretching up to 140 percent of its length without breaking, Live Science reports.

Unfortunately for those with visions of bulletproof clothing and elastic ligaments, the stuff has proved challenging to mass produce. Unlike the docile silkworm, aggressively carnivorous spiders don’t play well with others, and are difficult to raise in large numbers.

Synthetic production isn’t easy either. The silk is made up of protein molecules called spidroins, but their size and complexity makes them hard to work with. "In general, the larger the protein, the more difficult it can be to produce, and spider silk happens to be a very large protein, often in the range of 3,000 amino acids," Daniel Meyer, marketing executive of biotech company Spiber Inc., told The Wall Street Journal.

To overcome these challenges, a team of scientists from China, Spain, Sweden, and Britain turned to nature for the answers. Real spiders don't "weave" as much as they "extrude." Forcing a solution of spidroin proteins through an opening in their behinds, pressure and an "acid bath" work together to bind the molecules together into a fiber.

Copying this physical process as closely as possible, the team built their own web duct out of glass. Dipped in acid, the tip of this tiny tube, only one- to three-thousandths of a centimeter wide, apparently did the trick. The team estimates that one liter of bacterial solution (spidroin is made by genetically engineered bacteria) could produce one kilometer of silk. It’s not as strong as the real thing, but reportedly beats previous records.

Don't place your order for a bullet-proof shirt just yet though, because the technique isn't ready for mass production. "The spinning process used is also quite slow and would need to be faster if production is going to be scaled up and commercially viable," Neil Thomas, a professor of medicinal and biological chemistry at the University of Nottingham, who wasn't involved in the research, told The Wall Street Journal.

However, the natural process avoids harsh chemicals used in other methods, so the team hopes it may find biomedical applications such as bandages and sutures. The material's toughness and thinness make it less invasive than traditional options, and its biodegradability makes it a good candidate for the scaffold needed to repair wounds.

The new and improved substance is the latest in a string of recent developments in supermaterials, including self-healing polymers and strong-but-light 3-D graphene.