Look Ma! No eggs. This ancient reptile birthed live young

Live birth: Most mammals do it, some lizards and snakes do it, but archosaurs – a reptilian group that includes crocodiles and birds – don't... or so biologists thought.

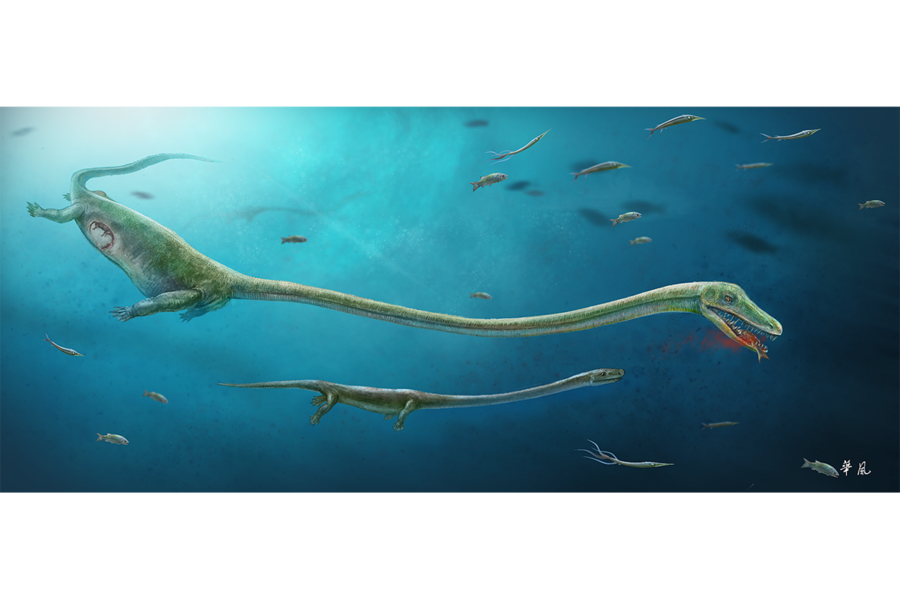

When a long-necked, marine archosauromorph died some 245 million years ago in what is now China, she was pregnant, according to a paper published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications. And now paleontologists are hailing this fossil as evidence that archosaurs might not have always been strict egg-layers.

"We commonly think of these aspects of animal biology as static or 'fixed' throughout evolutionary time, and cases like this demonstrate just how labile the evolution of animal form and biology can be," Dr. Nathan Smith, an associate curator at the Dinosaur Institute at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, who was not involved in the study of this new specimen, writes in an email to The Christian Science Monitor.

Egg-laying, or oviparity, is thought to be the ancestral reproductive strategy, with live birth, or viviparity, evolving later in some lineages. Viviparity isn't just the placenta-nourished embryonic development of mammals. It has also frequently evolved independently among lizards and snakes in a variety of forms, sometimes with babies hatching from eggs incubated inside their mothers.

So viviparity was known in mammals and lepidosaurs (the vertebrate group including lizards and snakes), explains study co-author Michael Benton, a paleontologist at the University of Bristol in Britain. But "nobody had ever discovered, in any of the living or fossil forms, any evidence that archosaurs could adopt live birth."

When the new specimen was first discovered and the researchers saw the small bones preserved within the larger animal's ribcage, they didn't want to jump to any conclusions. After all, this could have simply been this animal's last meal.

As the team examined the fossil, they realized that the two animals were indeed the same species. But it still could have been a case of cannibalism, Dr. Benton says in a phone interview with the Monitor.

The researchers are pretty sure that Dinocephalosaurus, as this animal is called, fed on fish because it has a small mouth and a long, thin neck, perfect for gulping down the long, slippery bodies of fish. Swallowing a chunky baby of its own species would have been quite the feat. Not only that, but the little bones didn't display any evidence of acid digestion, as would be expected for such a meal.

Furthermore, what Benton says is "quite strong evidence" against cannibalism is the position of the little animal within the bigger one. The big Dinocephalosaurus likely would have had to swallow the baby head first so it went down easily, but the little animal is oriented the wrong way.

Finding a little version of the bigger animal in the abdominal region "is about as close as you can get in the fossil record to direct evidence of reproductive mode," Christian Sidor, a paleobiologist at the University of Washington who was not involved in the research, says in a phone interview with the Monitor.

Daniel Blackburn, a biologist at Trinity College in Hartford, Conn., whose own research has focused on viviparity in reptiles, is convinced. "Based on the state of development of the embryo and its position in the body of the adult, it almost certainly is a developing fetus," he writes in an email to the Monitor. "Given the absence of any trace of an eggshell, as well as its advanced state of development, the embryo seems unlikely to be laid as an egg. Thus, the adult specimen is almost certainly a pregnant female with a developing fetus."

"Viviparity has previously been documented in only a few groups of extinct reptiles, notably ichthyosaurs, the giant mosasauroid lizards, and plesiosaurs," Dr. Blackburn says. "The authors' analysis extends live-bearing habits to an entirely new reptilian group, one in which it had not previously been suspected."

That may not be entirely true, says Xiao-chun Wu, a palaeobiologist at the Canadian Museum of Nature who was not involved in the new research. In 2010, Dr. Wu and colleagues reported evidence of viviparity in a choristoderan reptile. But there has been some debate around whether the choristoderans are lepidosauromorphs or archosauromorphs, he explains. And Wu asserts that these reptiles actually belong among the archosaurs.

Still, Wu says, this finding is significant because it increases the diversity of reproductive patterns among this group of reptiles.

And, Dr. Sidor says, even if choristoderan reptiles are viviparous archosaurs, Dinocephalosaurus is still the oldest example of live birth in an archosauromorph, as the choristoderans lived tens of millions of years later.

This pregnant Dinocephalosaurus could help corroborate a dominant idea about what makes a reptile stop laying eggs and start birthing live young: that viviparity is an adaptation necessary for reptiles to move to a fully aquatic lifestyle.

"Because eggs of reptiles (and birds) cannot be laid in water, aquatic reptiles have two choices: they either must come to land to lay their eggs (like sea turtles) or they must be viviparous (like ichthyosaurs and certain sea snakes)," Blackburn explains. "Dinocephalosaurus is highly specialized for aquatic life and probably could not come onto the land to lay its eggs."

"It's nice to see that we've got a pattern developing," Sidor says. According to that pattern, it fits that Dinocephalosaurus gave birth to live young. "It's nice to see that the fossil record is giving us glimpses of what we expected," he says.

And, Sidor adds, "it's nice to see a fossil like this come along that reminds us that evolution has developed this feature many times, and it's not something that is particularly special to [placental and marsupial] mammals."

Benton expects this discovery of live birth in archosauromorphs to open up many broad questions about why some groups have evolved to lay eggs and others give birth to live young. This might even lead to questions like why don't humans lay eggs, he says with a laugh.