Scientists need YOU to help make a solar eclipse movie

Do you want to be a filmmaking star? Or at least make a film of a star? The University of California needs your help.

As the clock ticks closer to this summer’s total solar eclipse, UC Berkeley and Google are partnering to carry out what they're calling the Eclipse Megamovie Project. By combining footage from over 1,000 cameras in the path of the eclipse, they hope to create a 90-minute “megamovie” that captures the phenomenon in a way no human being could alone.

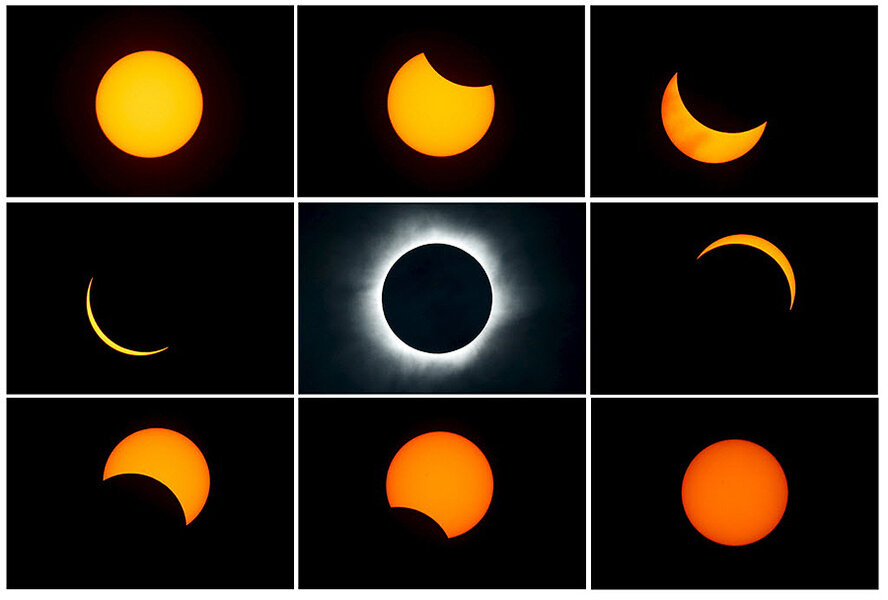

When the moon passes directly between the Earth and the sun on August 21, the center of its shadow will trace out a diagonal trail from Oregon to South Carolina. Observers located at the exact center of this “path of totality” may be able to see the total eclipse for as long as 2 minutes and 40 seconds as the shadow flies over the ground at up to 1,500 miles per hour.

The Eclipse Megamovie Project hopes to choose and train over 1,000 volunteers to record as much of the eclipse as they are able, after which the terabytes of video data will be stitched together to generate a complete, high-resolution record of the eclipse as viewed from the ground.

“We want everyone to know about the natural wonder, scientific importance and social impact of viewing a live total solar eclipse,” Laura Peticolas, a physicist who oversees the educational component of the Eclipse Megamovie Project, said in a press release. “It is truly a transformative, life-changing experience and we want to prepare people for that.”

The Eclipse Megamovie Project will also release an app this summer that will let anyone contribute to the effort with their smartphone. This footage will be used to create a second, lower resolution video.

While compiling the videos themselves is exciting, the team hopes to use them to answer some scientific questions, too. Of particular interest is the corona, the wispy filaments of plasma extending far beyond the solar surface.

Generally hidden against the brilliance of the sun, the corona can normally be studied using a device called a coronagraph, which physically blocks out the sun’s disk. It turns out the moon makes a great natural coronagraph.

Another point of interest is what’s called “Baily’s Beads,” little twinkles that appear around the rim of the moon as the sun shines through craters and gets blocked by peaks. Cellphone footage of these bright and dark spots can help astronomers map lunar features.

The team will be putting the crowdsourcing system through its paces this week during an annular eclipse in Patagonia, and those who miss their chance to participate this summer may have a second shot during the next US total solar eclipse in April 2024.

The Eclipse Megamovie Project is the latest in the recent trend of using so-called “citizen astronomers,” astronomy enthusiasts with little or no formal training who help the professionals sift through their data.

Modern instruments often collect far more data than scientists can handle, and when it comes to many kinds of analysis, current computer programs still can’t beat good old-fashioned eyes and human attention.

NASA recently invited citizen astronomers to help comb through images of nearby interstellar space to search for dim objects, such as an undiscovered planet or dwarf star, that might trick their computer software.

“There are just over four light-years between Neptune and Proxima Centauri, the nearest star, and much of this vast territory is unexplored,” lead researcher Marc Kuchner, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, said in a press release. “Because there’s so little sunlight, even large objects in that region barely shine in visible light. But by looking in the infrared, WISE may have imaged objects we otherwise would have missed.”

For any discoveries that lead to published work, the citizen astronomer will share credit, a point that can complicate the emerging field of collaboration between the public and scientists, as The Christian Science Monitor reported last fall:

The rise of citizen science has raised new, difficult questions about the ownership of data. In the publish-or-perish world of scientific research, professionals depend on authorship.

“But if citizens don’t get acknowledged, there’s a real sense of expropriation of their work,” Bruce Lewenstein, a professor of science communication at Cornell University tells the Monitor. “Citizens who have done mostly data gathering, should they be authors? In some fields, that type of work earns authorship. In other fields, it doesn’t.”

Citizen scientists interested in contributing their time and their cameras to the study of our sun and moon during this summer's eclipse can sign up for updates on the Eclipse Megavideo Project’s website.