Ancient skulls unearthed in China could belong to little-known extinct human species

In 2007, researchers from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing were finishing up an archaeological dig in Lingjing, China, when a team member spotted some quartz tools poking out of the mud. After extending the dig, the tools were extracted, revealing an even more significant discovery: a small, ancient skull fragment approximately 100,000 to 130,000 years old.

Over the next few years, the researchers returned to the site multiple times, finding more cranium pieces until they were able to reconstruct two partial skulls from more than 40 separate fragments.

But when the team analyzed the skull fragments, they realized that the skulls neither fit the bill for Homo sapiens nor Neanderthals but that they shared characteristics of both human species. Ultimately, the researchers were unable to positively determine exactly what kind of human the skulls belong to, opening the door to a wide range of intriguing possibilities.

In an article published Friday in the journal Science, the researchers note that the skull fragments date to the Late Pleistocene epoch, a time marked by the expansion of H. sapiens and the extinction of other species in the genus Homo. During the early part of that epoch, Neanderthals roamed Europe and western Asia while humans began to journey out of Africa. But fossil records of human species in Eastern Asia from that time period are thin, muddying the picture of that era for a substantial region of the planet.

The skulls found in China were found to bear very close resemblances to those of Neanderthals, including a very similar inner ear bone and a prominent brow ridge. But the brow ridge was much less pronounced than one would expect from Neanderthals, with a considerably less dense cranium, as one might expect in an early H. sapiens. Researchers also found that the skulls were large by both modern and Neanderthal standards, with a whopping 1800 cubic centimeters of brain capacity.

"They are not Neanderthals in the full sense," study co-author Erik Trinkaus, a paleoanthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis, told Science Magazine.

So what are they? It's hard to say, since the skulls contain features associated with modern humans, Neanderthals, and other Eastern Asian humans from the epoch.

"The overall cranial shape, especially the wide cranial base, and low neurocranial vault, indicate a pattern of continuity with the earlier, Middle Pleistocene eastern Eurasian humans. Yet the presence of two distinctive Neanderthal features ... argue for populational interactions across Eurasia during the late Middle and early Late Pleistocene," said Dr. Trinkaus in a statement.

Essentially, the skulls seem to belong to an unknown species that is none of the above – or, to be more accurate, a mix of all of the above.

"I don't like to think of these fossils as those of hybrids," study co-author and anthropologist Trinkaus told News.com.au. "Hybridization implies that all of these groups were separate and discrete, only occasionally interacting. What these fossils show is that these groups were basically not separate. The idea that there were separate lineages in different parts of the world is increasingly contradicted by the evidence we are unearthing."

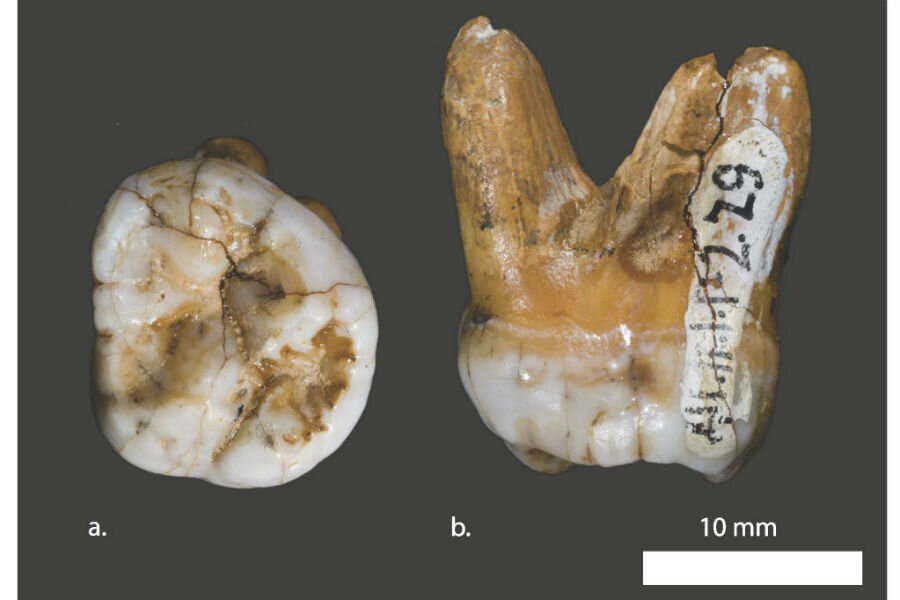

While this specific group of early humans the skulls belong to might never have been discovered before, it is possible that the remains may belong to a little-known hominid species known as Denisovans, which existed around the same time and mixed with modern humans and Neanderthals. But there's one catch: scientists don't have any Denisovan skulls to compare the China samples with. Only a few Denisovan remains have been previously uncovered, including a single finger bone and a large tooth, which scientists determined was distinct from Neanderthals and modern humans through DNA tests.

"It is not possible to infer skull morphology from ancient DNA directly," Phillipp Gunz, an evolutionary anthropologist at the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig who was not involved in the study, told The Washington Post. "I therefore hope that future studies will be able to extract ancient DNA from these or similar specimens," though he added that many of the features in the skulls did match up with what many experts imagine Denisovan skulls to be like.

Until a definitive DNA test is conducted on the skull samples, their true origins will remain a mystery. But there's still a lot that can be learned from them in the meantime.

"The biological nature of the immediate predecessors of modern humans in eastern Eurasia has been poorly known from the human fossil record," said Trinkaus, in a Washington University, St. Louis statement. "The discovery of these skulls of late archaic humans from Xuchang substantially increases our knowledge of these people."