Stereo spacecraft set to search for lunar origins

OK, maybe it's a long shot. But as long as we're passing through, we'll a look anyway.

That's the approach scientists are taking with a pair of sun-watching spacecraft called Stereo. The pair was launched in 2006. They've been trained on the sun, returning images scientists can combine into 3-D views of the star. Researchers now want the duo to hunt for debris that might have been left over from the construction of a hypothesized impactor that smacked Earth 4.5 billion years ago. You can read more about it here.

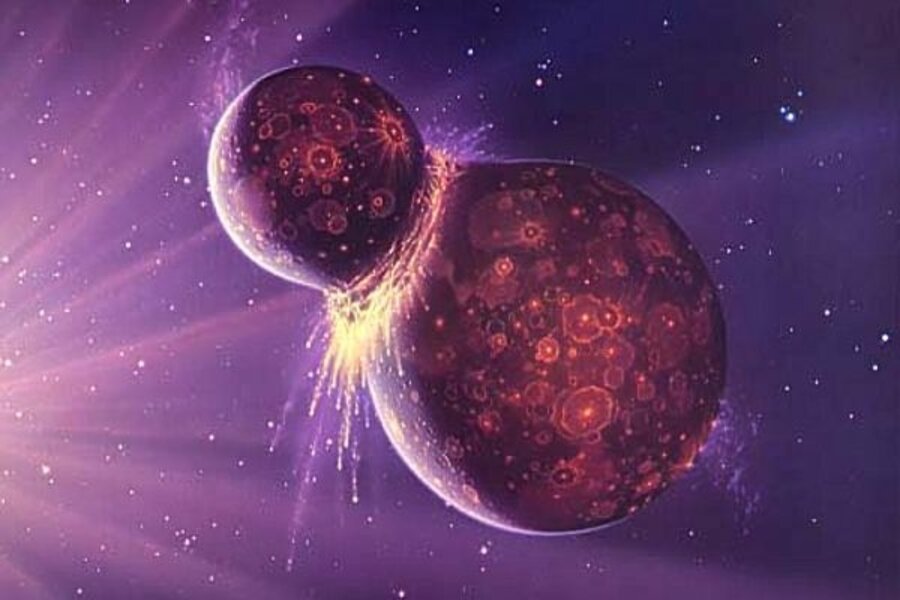

Scientists have dubbed the hypothesized Mars-sized planet Theia. And after the collision? Well, let's just say Theia was toast.

The glancing blow stripped the impactor of its outer layer, along with some of Earth's. Its iron core is thought to have melted and much if it merged with Earth's iron core. The outer material – mostly belonging to the impactor – gathered itself together and formed the moon.

That's the story scientists had pieced together up to 2005. And it explains a lot, astronomers say. Among other things, it explains why the moon has such a tiny iron core. It also explains why the the geochemistry of Earth and moon materials are so similar – they formed in the same region of the nebula of dust and gas that surrounded the early sun.

But where did the impactor actually come from?

Enter Princeton University researchers Edward Belbruno and Richard Gott III. They suggest that it probably formed in one of two gravitational "sweet spots" (regions, really) roughly 60 degrees in front of and behind Earth along its orbital path around the sun. You can find their paper proposing the idea here. It was published in 2005.

Anything in either of these so-called Lagrange points appears to be stuck in that region – a spacecraft in one of these regions needs few if any nudges from its thrusters to keep it there. (To see a diagram of these sweet spots, select the second "photo" in the image panel above.)

As the planets formed, another planet – Venus, perhaps – gained enough mass to affect Theia. In essence, Venus's gravity could have tugged Theia out of its gravitational comfy spot at either of these two locations and sent it on a one-way trip toward Earth.

Debris left over from Theia's formation, in the form of asteroids, might still be in one of these locations. After all, the duo noted, Jupiter has two clutches of asteroids, dubbed the Trojans, hanging tight at its so-called Lagrange 4 and 5 regions.

So Stereo is getting set to hunt for asteroids at the Earth-Sun L4 and L5 points. As with any asteroid hunt, the satellites' cameras will scan the L4 and L5 regions for points of light that move against the background field of stars.

If it finds any asteroids, and they have a mineral makeup similar to that of the Earth and moon, it would bolster the case for L4 or L5 being Theia's birthplace.