With help of lasers, NASA hopes to create the 'coldest spot in the universe'

While space has long been described as “the final frontier,” different scientists want different tools for mapping it out. Astronomers crave more powerful telescopes; planetary scientists have a long “wish list” of orbiters, landers, and rovers.

But quantum physicists, who study matter and energy on a subatomic scale, want near-zero temperatures and microgravity. An experimental chamber set to be installed aboard the International Space Station this summer will deliver both.

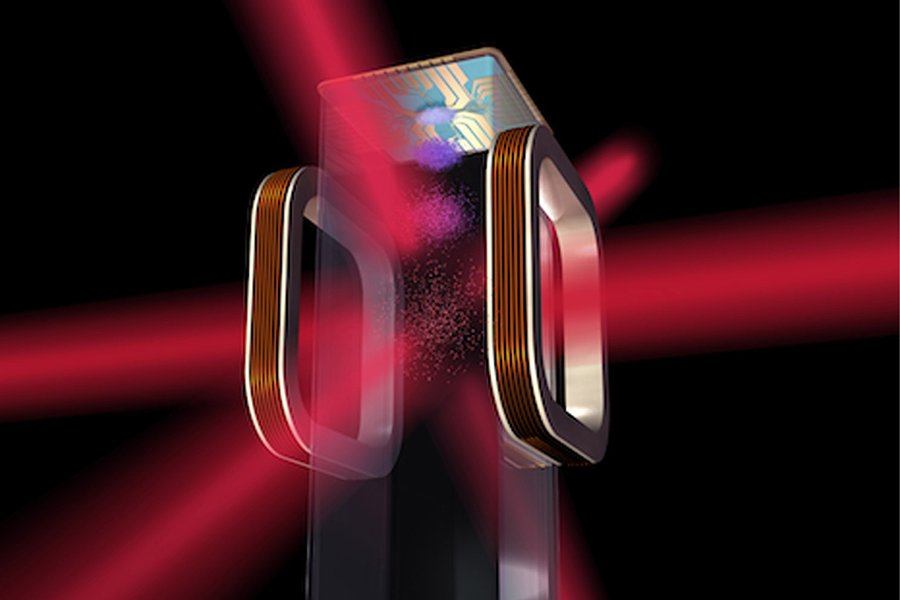

Dubbed the “Cold Atom Laboratory,” the ice-chest-sized facility is designed to use a vacuum chamber, lasers, and an electromagnetic “knife” to slow down gas atoms until they’re almost motionless, bringing temperatures inside to a billionth of a degree above absolute zero – what NASA describes as “the coolest spot in the universe.”

Observing atoms at such low temperatures, in the near weightlessness of space, could drastically change our understanding of matter and energy.

“Studying these hyper-cold atoms could reshape our understanding of matter and the fundamental nature of gravity," said CAL project scientist Robert Thompson in a Jet Propulsion Laboratory statement.

High on the new facility’s agenda will be research into an exotic class of matter called Bose-Einstein condensates, which were first theorized by Albert Einstein and another physicist, Satyendra Nath Bose, in the early 20th century.

In this state, when brought close to absolute zero, atoms clump together and enter the same energy state, making them impossible to distinguish from one another. Like light, they more closely resemble a wave.

Scientists first achieved this state on Earth in 1995, but it lasted only for a fraction of a second. According to NASA, “on the International Space Station, ultra-cold atoms can hold their wave-like forms longer while in freefall.” Dr. Thompson “estimated that CAL will allow Bose-Einstein condensates to be observable for up to five to 10 seconds,” and possibly for hundreds of seconds with future upgrades.

And without the interfering pull of Earth’s gravity, scientists say the strange world of quantum mechanics will get super-sized. In 2014, Thomson predicted that “we’ll be able to assemble atomic wave packets as wide as a human hair – that is, big enough for the human eye to see.”

That wouldn't just make things easier for quantum physicists. A better understanding of quantum mechanics could prove indispensable to future space explorers.

Wave-like atoms could eventually be used to “map out 'the shape of the gravity that we feel' on a planet whose natural features – underground caverns, melting ice caps – create small but measurable effects on its gravitational pull,” The Christian Science Monitor reported in 2014, quoting Jason Williams, an atomic physicist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Other potential benefits include more accurate atomic clocks and more powerful quantum computers.

But these payoffs depend on a rigorous pre-launch testing regimen currently proceeding under the direction of JPL’s Dave Aveline.

"The tests we do over the next months on the ground are critical to ensure we can operate and tune it remotely while it's in space, and ultimately learn from this rich atomic physics system for years to come," he explained in the JPL statement.