In the early 1830s, natural rubber was all the rage, but the excitement faded. People realized that their rubber would freeze and crack during the winter or melt into a sticky, smelly goo during the summer. Natural rubber could not stand extreme temperatures, so its popularity quickly died.

Charles Goodyear spent years trying to overcome rubber's problems, and he only succeeded by mistake.

Goodyear tried various powders to dry up the stickiness, but to no avail. Everything kept melting. These expensive experiments pushed his family into debt and resulted in jail time. Yet even in prison, Goodyear was undeterred from his goal. Some called him a mad man.

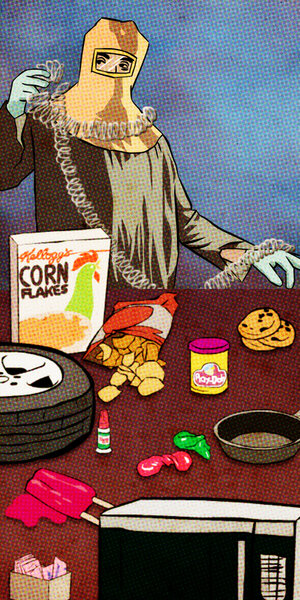

According to a biography of Goodyear in Reader’s Digest, he walked into a general store in Woburn, Mass., to show off his rubber products. This time the rubber had sulfur in it to act as a drying agent. Goodyear got so excited that the rubber flew out of his hands and landed on a hot stove. When he examined it, he noticed that it did not melt, but instead charred black. After poking and prodding, Goodyear also noticed that it still had the springy surface texture of rubber, the “gum-elastic” it was known for. Goodyear had made rubber weatherproof.

Another tale tells a different story: Goodyear absent-mindedly turned out the lights to his makeshift lab and spilled his vials and test tubes containing sulfur, lead, and rubber onto a still-hot stove. The result was the same, a charred rubber-like substance that didn’t melt in the extreme heat. After testing in freezing temperatures, Goodyear finally succeeded in reaching his goal, and it only happened because of a careless mistake.

After many patent battles, Goodyear died still in debt. He didn’t start the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. – the American company was instead named in his honor.

"Life," Goodyear wrote, "should not be estimated exclusively by the standard of dollars and cents. I am not disposed to complain that I have planted and others have gathered the fruits. A man has cause for regret only when he sows and no one reaps."