MS-DOS computer viruses live on in the Internet Archive’s Malware Museum

Loading...

Before clickjacking, infected downloads, and ransomware that demands a payment in Bitcoin, computer viruses spread through infected floppy disks.

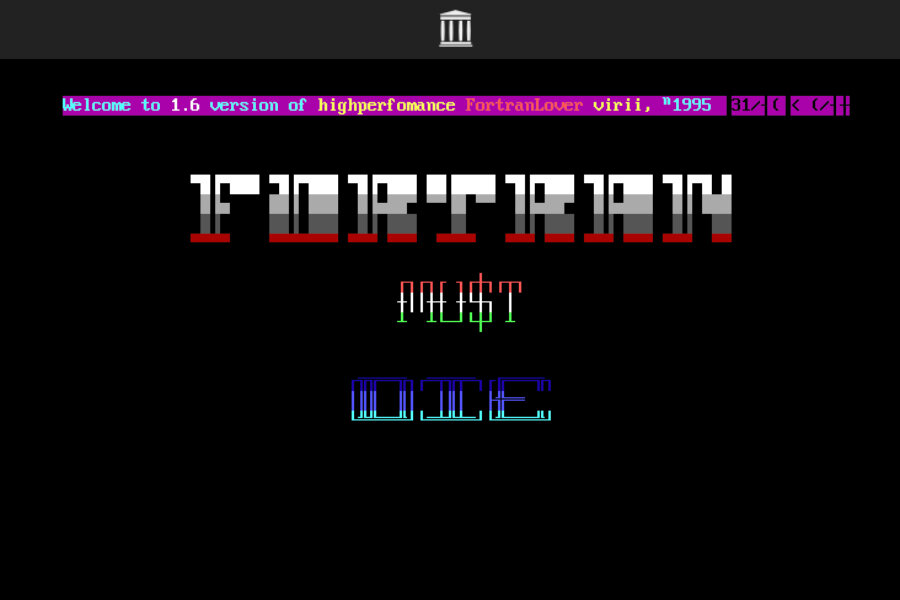

Starting with the first malicious viruses to emerge “in the wild” in the mid-1980s, the software would attack MS-DOS or Apple operating systems, changing or deleting data and perhaps leaving a triumphant or insulting message on the screen as they did so. The programmers who wrote these viruses weren’t trying to extort users; instead, early malware was a way for them to test their coding skills while sowing chaos in the process.

The Internet Archive’s Malware Museum, which launched this week, collects dozens of examples of MS-DOS viruses from the 1980s and 1990s. The viruses have been shorn of their malicious code, and can be executed safely inside a purpose-built DOS emulator running in a browser.

Some display simple designs such as hearts or ocean scenes as they run. Others show messages that would be threatening, save for their questionable grammar (“You have do many works today. So, I will let your computer slow down”). One, called “Casino,” gives the user five chances to win a game of slots. If the user wins, the virus disappears; if the user loses, Casino deletes the computer’s data and insults the user in a way that sounds like a teenager trying out swear words for the first time.

Why preserve old malware? One of the Internet Archive’s purposes is “offering permanent access … to historical collections that exist in digital format,” and viruses are unquestionably a part of computing history, right along with digital images, games, and music.

Separated from their destructive capabilities, the viruses’ messages – some playful, some threatening, many grammatically tortured – seem quaint. Compared to the relatively advanced malware of the last five years, which employs tracking cookies, command-and-control servers, and nigh-undetectable code, a virus that does nothing more than advocate for the legalization of cannabis is refreshing in its simplicity.

Most of the viruses come from the personal collection of Mikko Hyppönen, the Chief Research Officer at antivirus company F-Secure. Mr. Hyppönen has been collecting malware since 1991, and still has many early viruses in their original format, contained on five-and-a-quarter-inch floppy disks. Others were gathered by Jason Scott, a digital archivist and curator of the Internet Archive’s software collections.

Now that the viruses have been collected in one place, anyone can experience anew the feelings – ranging from mild annoyance to panic – that came with having one’s computer infected with malware in the pre-Internet Age.