Will Google's Allo chat app spy on you?

Allo is always watching – but will it invade your privacy?

On Wednesday, Google debuted the latest in a long line of mobile chat apps: Allo. The company’s marketing strategy for the new platform focuses largely on Google Assistant, an AI helper designed to set Allo apart from rivals iMessage and WhatsApp.

But the app’s core feature may also be its downfall. To properly function, Assistant needs to save your conversations – much to the chagrin of security-minded users.

In some ways, Allo looks a lot like its competitors. Like iMessage, it’s an easy-to-use chat app with a minimalist design. All the standard features – group chats, goofy stickers, picture sharing – are accounted for.

But then there’s the Google Assistant. This AI helper can do all the things Siri and Alexa can do, but it's integrated into Allo’s chat platform. It can share your flight schedule with relatives, settle trivia disputes in group chat, and fetch vacation photos from your camera roll. After a while, Allo’s Smart Reply feature will even attempt to guess how you’ll respond to certain messages, potentially sparing you the inconvenience of typing it out.

The catch: Allo chats are not end-to-end encrypted. In other words, Google can go back indefinitely to access your conversations. That’s because the app’s machine learning relies on previous chats.

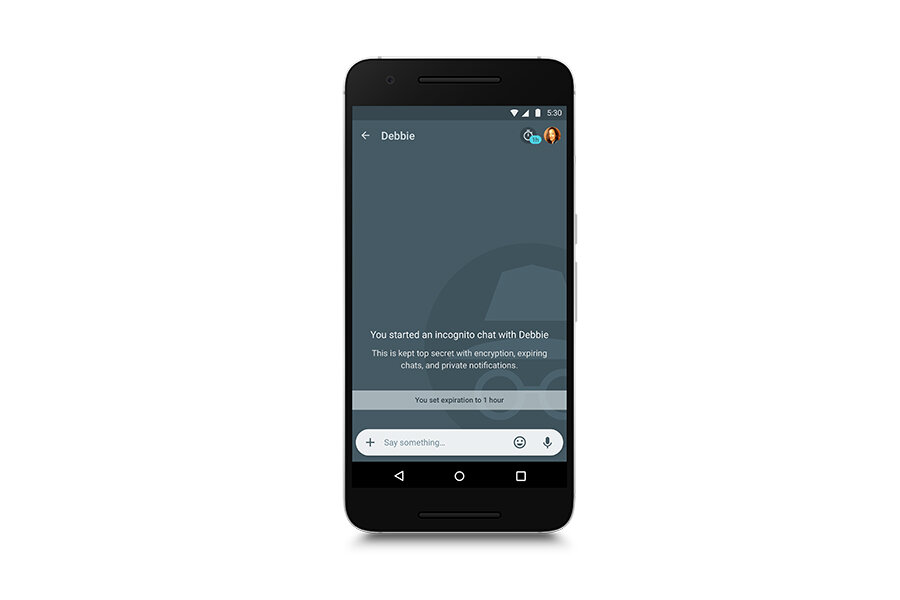

Google originally said that chats would only be temporarily stored within the app. But the company has since backtracked, the Verge reports. The current version of Allo permanently saves all messages by default unless users actively delete them. Users can chat in an encrypted incognito mode, but that setting disables Google Assistant.

Allo’s privacy settings have prompted criticism in cybersecurity circles. Even Edward Snowden weighed in.

But is Allo really going to spy on you?

In recent years, Google has come under scrutiny for sharing data between its many platforms. In 2015, a privacy watchdog group filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission after school-bound Chromebooks were found to mine students’ browsing data.

But most users won’t have any clandestine observers poring through their conversations. Rather, much of that information is used to help Google target ads. And in the end, that may not even matter – researchers say users are more willing than ever to share their data.