The novel by tweet

| New York

Nick Belardes believes in brevity. He hews close to that hallowed maxim, beloved by middle school English teachers and old-fashioned newsmen alike: Keep it simple, stupid.

"People need to be educated to be more concise," says Mr. Belardes, a journalist and novelist based in Bakersfield, Calif. "Every day, we get these super-long-winded e-mails. You can communicate more if you say a little less."

Earlier this year, Belardes was cleaning out his desk drawer when he came across an unfinished manuscript for a workplace novel called "Small Places."

He briefly considered shipping the thing off to publishers for consideration. Instead, he decided to serialize "Small Places" on Twitter, a popular microblogging site.

"It was a natural fit," he remembers. "So many people are sitting in their gray cubicles, reading Twitter. They're looking for something easy to digest. I thought I could put a smile on their face."

Twitter was launched in 2006, as an alternative to long-form blogging platforms such as TypePad and Movable Type. The site allows posts – or "tweets" as they are commonly known – of only 140 characters or less, and users typically fall back on Internet slang to get their point across. Most use the site to broadcast personal errata, from sock color to recreational softball scores to notes on the weather ("Sure is cold over here in New York," one might point out.)

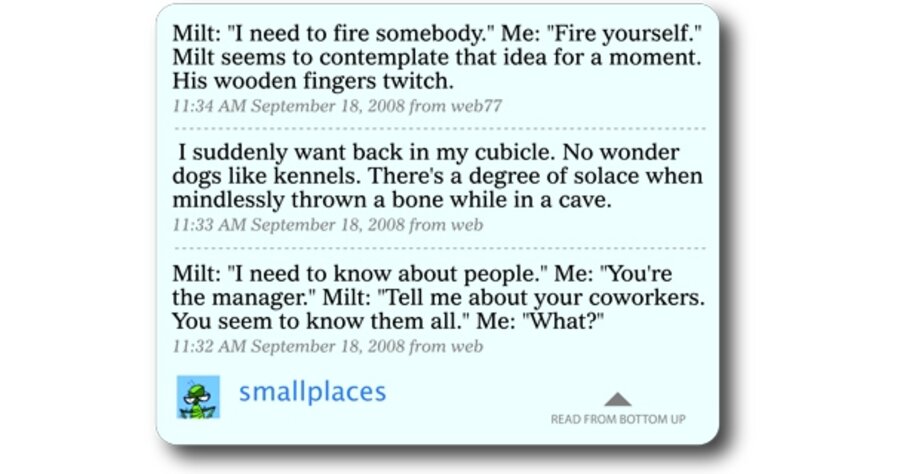

But Belardes found Twitter equally effective for fiction. Slowly, in fits and starts, he adapted the manuscript to terse, comedic tweets, frequently digressing into colorful observations. "I've grown to like small places," runs the first post. "I like bugs, bug homes, walking stick bugs, blades of grass, ladybug Ferris wheels made out of dandelions."

As the narrative spooled out over some 400-plus tweets, "Small Places" (twitter.com/smallplaces) began to attract a sizable audience. Approximately 4,700 readers now follow the novel, and it has quickly climbed the Twitter charts, eventually landing among the Top 100 profiles. Belardes has become a figurehead of sorts for a decidedly micromedia movement: the novel by tweet. Although exact numbers are hard to come by – many projects have been abandoned and more crop up every week – the idea appears to have real ballast among the millions of Twitter fanatics, who crave rapid bursts of overshare.

"I think social media is all about stories," says Tabitha Grace Smith, a media strategist and a contributor to the site socialmediaworld.com. "We tell stories, we participate in each other's life story – so 'Small Places' and other novels on Twitter are a logical progression from our desire to interact, share, and grow together."

For Belardes, the Twitter novel simply represents a natural progression of prose form. "Everything in the information age works at an incredible rate of speed," he says. "I don't think people like to admit it, but our attention spans have shortened. I see it happening to myself. And Twitter is an important tool for being concise."

In this way, "Small Places" isn't so different from the serialized comic strips published in the Sunday funnies – every episode ends in a cliffhanger or an open-ended question.

Other authors see the medium as a way to snare audiences traditionally adverse to classic fiction. Screenwriter Jay Bushman, for instance, has adapted the Herman Melville novella "Benito Cereno" into a Twitter science-fiction piece titled "The Good Captain." "I love it when classic stories are put into different frameworks that can bypass an audience's inherent distrust of 'literature' and something that is supposed to be good for them, hence boring," says Mr. Bushman. "Most of what we consider classics were the blockbuster entertainments of their day."

In July, Sarah Schmelling, a writer for the McSweeney's magazine website, brought this theory to its logical, side-splitting conclusion. The project was called "Hamlet (Facebook News Feed Edition)," in a nod to a Twitter-like broadcasting feature on the ubiquitous social network. A sample line: "The king thinks Hamlet's annoying."

Bushman is currently developing "re-imaginings" of "Pride and Prejudice," by Jane Austen; "Dracula," by Bram Stoker; and "Moby Dick," by Melville. He also has a well-trafficked group blog called the Spoon River Metblog (http://spoonriver.metblogs.com), which he calls a "modernalization" of "The Spoon River Anthology," by Edgar Lee Masters.

"I think there's value in looking at these media as conduits for serious storytelling," says Bushman. "I like to think of this kind of work as 'embedded fiction.' That is, in your daily online life, you have lots of sites, feed, channels you get information from. And it's all nonfiction – news, e-mails from friends, status updates. And I want to embed little bits of fiction within these real streams and, hopefully, blur the line between the real world and the story world."

As Belardes and others have pointed out, the novel by tweet is really a digital extension of flash fiction, an established literary genre which relies on constrained word counts and a florid style to convey often complicated narratives. (H.P. Lovecraft was a pro at flash fiction; so, memorably, was Ray Bradbury.) Projects such as "Small Places" and "The Good Captain" also have an analog in the so-called "cellphone" novels which have filled bestseller lists in Japan. "You have to ask yourself, 'What is a novel?' " Belardes says. "You can't be stuck on the idea of a novel being a book you hold in your hand."

In recent months, he points out, Twitter has become an accepted tool among media outlets, including The New York Times, which used the service to help cover CMJ, an annual music showcase based in Manhattan. Other papers have reported on funerals, press conferences, and presidential debates by tweet.

Still, some writers see Twitter as nothing more than a useful marketing device for their own literary projects. Brandon J. Mendelson, the author of a work in progress called "The War on Literacy" (www.twitter.com/TWOL), says Twitter is "a clever way to use a [fairly] new service to build an audience. For writers, the competition is stiff, so we need every edge we can find, but I don't think this is the future at all. I agree mobile is the future, but 140 characters at a time?" Mr. Mendelson asks. "We want and demand more than that."