Nation-building at home: Civics 101

| Portland, Ore.

Six sophomores at Grant High School sit, shoulders slumping slightly, before two lawyers. The room fills with nervous expectation. Here, the Constitution is a competitive sport, and students need to dazzle: They will have six minutes to explain to these local lawyers the context, and every important detail, of an 1819 Supreme Court case – McCulloch vs. Maryland, a landmark case in which Chief Justice John Marshall expanded the power of the court with the stroke of his pen. They need to be smart, but also to be witty to tie this old history to current affairs and to showcase teamwork. It's a lot to carry on one's shoulders – hence, perhaps, the slumping.

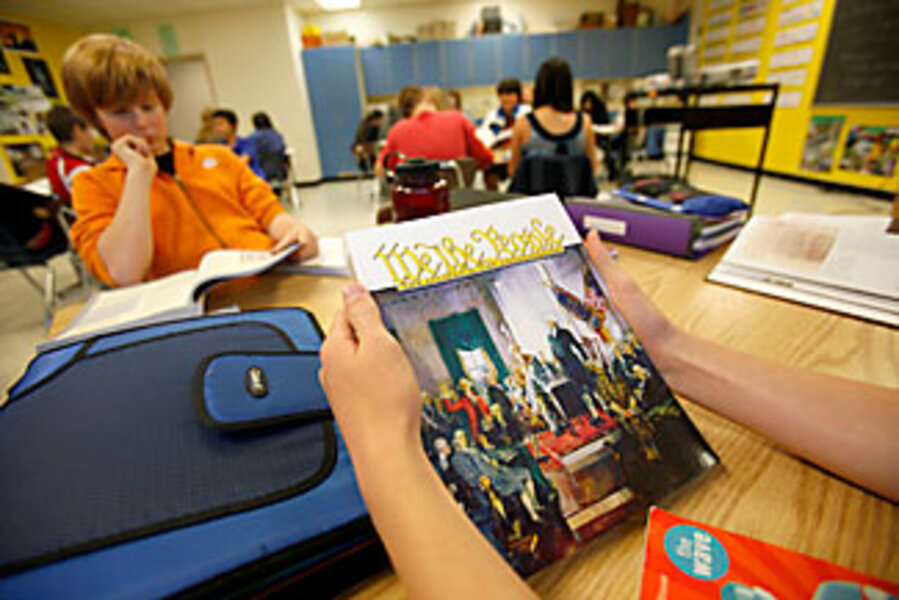

These are early rounds of after-school practice for "We the People," a national curriculum and competition implemented in Oregon by the Classroom Law Project, a civics education initiative. Grant has held the state title for the past seven years.

"I figure it's my responsibility to understand how American government works. Not enough other people are willing to do that, and someone has got to be responsible," says Patrick Streckert. "It's like being the designated driver for a country."

Tonight, Patrick and his classmates explain the constitutional principles behind the case. It's a great history lesson and a good primer in the philosophy of politics; it even looks like a little bit of fun. But is a debate on the ins and outs of a centuries-old Supreme Court decision really that relevant to contemporary issues?

The answer, the students insist, is "more than you'd guess." Case in point?

"Healthcare," says Ednan Louie, a bit incredulously. "Some people think healthcare should be something the states regulate, but Obama says he wants a national healthcare plan."

With a competition that will ask them to "testify" about the ins and outs of the nation's founding documents and legal precedents – before a mock congressional hearing panel made up predominantly of professional lawyers – and an advanced class in government to get them ready, these students are getting an extreme dose of civics education. It's an area of study that teaches students how the American political system works. Once a ubiquitous if unloved staple in the American classroom, civics tapered off 40 years ago.

These days are prime for a much-needed comeback, observers say.

"Today, at the most, 20 percent of our students get a moderate civic education, and fewer than that get an outstanding one," says Charles Quigley executive director of the Center for Civics Education, in Calabasas, Calif. "The vast majority of American kids are graduating high school basically ignorant of their own political system and how to participate confidently and responsibly in it."

The numbers are, indeed, dismal. Only 5 percent of graduating high school seniors could explain the US political system's checks on presidential power, and only two thirds had at least a basic understanding of the system and its functions, according to the National Center for Education Statistics' 2006 "Nation's Report Card" on civics. The center also found that students in higher income schools and schools with high parental involvement exhibit a greater mastery of government studies. Meanwhile, the Civic Education Research Group at Mills College, in Oakland, Calif., found that college-bound and white students get more – and better – civic education opportunities than their minority counterparts.

That finding makes some sense, say teachers. Both the quantity and quality of civics education, says Susie Marcus, who trains teachers on Oregon's Classroom Law Project, "depends on the goodwill of the teacher, and teachers are battered about."

Whether they teach in at-risk or affluent schools, teachers need support – time, training, and resources – to get good civics education off the ground, says Marilyn Cover, who directs the Classroom Law Project. But the content, she says, is crucial: Oregon students scored only a "high D" on a basic civics test, according to the Oregon Civics Survey.

That survey also found that a common civics substitute – service learning, in which students volunteer in the community – fails to translate into political knowledge, and that only 29 percent of students trust the government.

Many students at Lake Oswego High School, in an affluent suburb of Portland, say their rigorous civics education has actually made them more suspicious of government, even more jaded.

Senior Matthew Bowen says he sees a lot of self-interest, some of it healthy, driving political decisions in early America, but he thinks that characteristic has taken a wrong turn: "If you look at it now, there's so much more lobbying, polarization, and partisanship. It's so much harder to make a positive change now."

But not everyone in Matthew's advanced government elective feels so pessimistic. "I think most people don't go into politics to corrupt the government," says senior Britney Debnam. "I think most people want to do good."

Though all states require some education in American government, civics isn't an indicator on major testing evaluations like those mandated under No Child Left Behind, which risks making it an afterthought in classrooms already frenzied by bubble tests and other educational priorities.

But the subject fell off the radar long before standardized testing debates. Civics education was required in most schools until the 1960s, Mr. Quigley says. It was, he says, "very, very dry and not related to political reality." Support for its place in the curriculum fell off.

But the intense political engagement of the 1960s, says Julie Reuben, a professor of education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, caused civics "to become threatening to educators. Students engaged in protests and behavior that was seen as unruly."

Ms. Reuben, who specializes in the history of American education, says the drought of student engagement in the late 1970s and early 1980s had the reverse effect: Educators, worried about students who could name Microsoft founder Bill Gates before Founding Father James Madison, returned civics to the classroom. They banded together and formed nonprofits, wrote curricula, and otherwise pushed for civics. But not until the early part of this century, Reuben maintains, could it be said that civics really made a comeback.

Even today, supporters struggle with the tension between teaching students how the levers of power work and encouraging students to pull those levers.

"Once you tell them that they have rights, and [how to] assume positions of power, they want to do that for real," says Gerrit Koepping, who teaches government at Lake Oswego High School in Lake Oswego, Ore.

Mr. Koepping and his colleagues got more than they bargained for two years ago, when students took what they learned in their elective Political Action Seminar into the real world – and irked the city council by seeking to extend the town's 10:15 p.m. curfew for 14- through 17-year-olds. Students challenged it as unconstitutional because it didn't allow exceptions for those attending protests, making political speeches, or attending religious services. It was also inconvenient for students who had late-shift jobs.

Students met with the city council and the city attorney but failed to win a change. The American Civil Liberties Union then filed suit on their behalf. The suit was dropped after the city changed the curfew to midnight.

"It certainly pushed our comfort level," says Bruce Plato, the Lake Oswego principal. "If we let students say, 'We're going to see the mayor,' " he says, then teachers and administrators have to decide where in the process that happens. "We don't just go get in people's faces because we don't like something."

The question of when to raise one's voice is at the center of another, unusual approach to civics education run by Facing History and Ourselves (FHAO), a Massachusetts-based teacher training organization. Unlike many civics lessons taught in government or American history classes, FHAO teaches participatory democracy through study of the Holocaust.

"For a democracy to survive…requires the active engagement and participation of its citizens," says Martin Sleeper, the group's associate executive director. "So we look with kids at the decisions that…were made in history, still have to be made today, [and at] connections that are made between the past and today."

The idea, Mr. Sleeper says, is to educate students to know not only how to raise their voices, but when. The curriculum focuses on bystanders in the Holocaust and teaches students how to be "upstanders," who speak up in the face of prejudice or oppression.

"It's not only a program in civic education, but in moral education," Sleeper says.

That's a line not all teachers feel comfortable crossing.

"It gets dicey when it comes to values," says Mary Crittenden, who teaches eighth-grade history and language arts at West Sylvan Middle School in Beaverton, Ore.

There are days, however, when controversy will inevitably find its way into the classroom.

Karl Atkins, who teaches freshman social studies at Scappoose High School in Columbia County, a conservative outpost north of Portland, taught a unit on immigration "the same year we passed a restrictive anti-immigration measure, and in my class [was] the son of the guy who got it on the ballot."

Mr. Atkins tries to translate political hot buttons into learning opportunities. Ultimately, he says, students need to understand a picture bigger than any single political issue.

"As kids, they're just trying to sort out a really confusing world. They see a lot of yelling on TV," says Atkins. His job, he says, is to "get rid of the yelling and talk about what's happening underneath."