On the Bowery: movie review

One of the most famous of all American independent films, Lionel Rogosin’s “On the Bowery,” which is being revived in a restored print, still stands up after all these years. Made on a shoestring in 1955, it’s not exactly accurate to call it a documentary. Dramatized nonfiction is closer to the truth.

Rogosin, a first-time filmmaker, was inspired by the great documentarian Robert Flaherty, who took his cameras into northern Canada’s Hudson Bay and reenacted the lives of the Eskimos there for his classic “Nanook of the North.” Rogosin invested his own money – about $60,000 – on his project, and spent months hanging around the Bowery, New York’s skid row.

At first, with his cinematographer Richard Bagley, he intended simply to record what he saw, but the formlessness of the footage prompted him to construct a story line taking place over three days about a drifter who arrives in the Bowery.

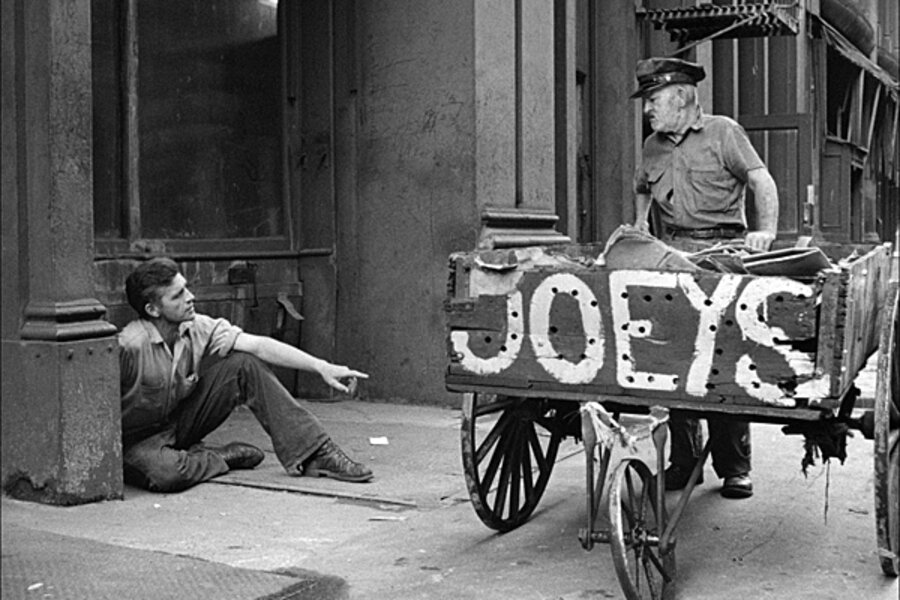

Rogosin found his drifter – a 30-ish railroad worker named Ray Salyer, worn down but still handsome, who arrives suitcase in hand. He also found a puckish, grizzled old gent named Gorman Hendricks, who befriends Salyer in the Round House bar and teaches him the ropes. All of their scenes, as is true of virtually everything else in the movie, grew out of real experience. What Rogosin was attempting was nonfiction with the texture of fiction.

Nowadays, the term “reenactment” has a bad connotation from all the phony reality TV shows, but Rogosin understood that, by allowing these Bowery denizens to, in effect, play out their own stories, he might get at a larger truth than could be arrived at either by straight fictional or nonfictional means. (It’s the same effect that Kent MacKenzie was after in his wonderful independent movie “The Exiles,” about native Americans in Los Angeles, which, like “On the Bowery,” was reissued by Milestone Films.)

Of course, the demarcation between fiction and nonfiction is never absolute. It’s also true that there are moments when “On the Bowery” seems shatteringly false. The “dialogue” spoken by these men, even if it originated with them, often seems stilted and awkwardly delivered. I much prefer, at least in theory, the Frederick Wiseman school of documentary, where you train your cameras on a situation without any overt prodding or intervention – or invention.

But “On the Bowery,” despite these lapses, is unforgettable. As a record of a time and a place in the history of New York, it’s essential. As a depiction of men at the bottom of their lives, it has the same sorrowful, accusatory force as a great Depression-era photograph by Dorothea Lange or Walker Evans. (James Agee, who collaborated with Evans on “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men,” and assisted in the screenplay for the great independent New York street movie “The Quiet One,” was originally going to write “On the Bowery” but died before it got going. Mark Sufrin is the credited writer.)

The grim truth of this movie is revealed by what became of its leading protagonists. Hendricks died shortly after filming from cirrhosis of the liver, and Salyer, who looked a bit like Gary Cooper, reportedly turned down a $40,000 Hollywood contract. “I just want the Bowery and to be left alone,” he told a New York newspaper. He disappeared soon after and no one knows what became of him.

Playing with the 67-minute “On the Bowery” is “The Perfect Team,” a loving and evocative 45-minute account of the making of the film by Rogosin’s son Michael. Grade: A (Unrated.)

-----

More Monitor movie reviews: