The real story behind 'The King's Speech'

Loading...

| Los Angeles

This year's top Oscar-nominated film, "The King's Speech," bursts with narrative resonance – both in the story it tells and in the one behind the film's creation.

The true-life tale of Prince Albert, who overcame a lifelong stammer on his way to becoming King George VI, seems built to appeal both to Americans' love of self-reinvention and also Britons' complex blend of nostalgia and ambivalence where their royals are concerned. The movie brims with the universal appeal of a fairy-tale ending – both in terms of its plot and also in that it is a $12 million film that has garnered 12 Oscar nods.

As a quintessential triumphant underdog yarn, the story is pure Americana, says Steve Thompson, founder of MindFrame Theaters, an independent art-house cinema in Dubuque, Iowa.

"[King George] is a man with problems, just like us, so we relate to him," he says.

But in depicting a royal who puts duty above his personal pain, this version of history is "also pure British Empire," says Wade Major, who teaches the film and social justice program at Mount St. Mary's College in Los Angeles. It reinforces all the best values Britons attribute to themselves while it also humanizes the very notion of royalty – both past and present, he says.

The film is also well timed. It arrives as the British public finds itself face to face with the memory of another, more recent royal figure – Diana, Princess of Wales, whose own painful story hovers over the impending marriage of her first son, Prince William.

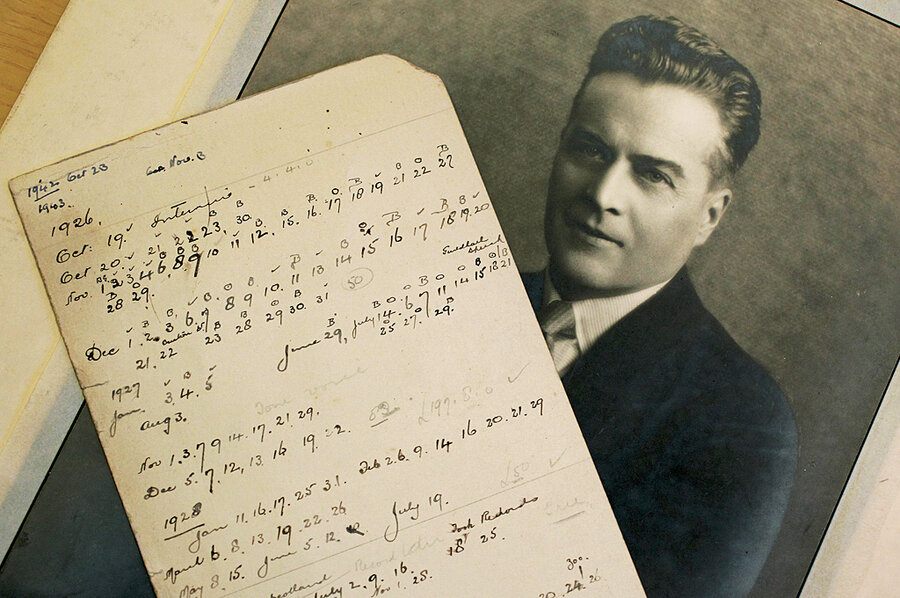

This is a wrenching moment for the British, says Mark Logue, grandson of Lionel Logue, the Australian actor and speech therapist – played in the film by Geoffrey Rush – whose unconventional techniques helped the second in line to the British throne (played by Colin Firth) gain his "voice."

The memory of Diana is everywhere, he says, speaking by phone from London. The film's story is a reminder of her appeal. "She was very human, with weaknesses and vulnerability, and the public had a great appetite for that," he says.

This film has been enthusiastically embraced by the British, points out Professor Major, who says that it underlines a shift in national attitudes. "The British want the royals to adapt; they do not want a replay of what happened with Diana," he adds.

Perhaps if the king's story had been told earlier, Diana's life story might have had a different outcome, notes Mr. Logue. But Queen Elizabeth (played by Helena Bonham Carter) refused to give screenwriter David Seidler her blessing to make a film about events of those days during her lifetime. And so, says Logue, "now becomes the perfect time, because people here are thinking about royalty in a new way." Everyone finally realizes that the monarchy has to change with the times, something Diana tried to do, but with little support from the British royal family, he says.

This deference to the former queen's desires drapes the making of the film with its own Cinderella story.

The king's travails are intensely personal for Mr. Seidler, who suffered from a childhood stutter himself after a wartime evacuation from England. He was keenly aware that the man who never expected to wear the British crown had labored mightily to overcome the same affliction.

"The king was my hero," he says simply, and a lifelong urge to tell the king's story was born almost as soon as he became aware of their shared challenge. When he acquiesced to the queen's request to delay telling her husband's story until her passing, he did not realize just how much patience that might require – the queen mother, as she was affectionately known after her daughter became queen, died in 2002 at age 101.

Seidler labored to shape the unconventional relationship between Logue and "Bertie," as his intimates called the prince, drafting both a play and a screenplay.

His own fairy-tale ending began shaping up when the mother of acclaimed director Tom Hooper attended the single staged reading of the play. She then persuaded her son that this should be his next project.

But even with a big-name director behind the venture, "there were literally dozens of times that this project nearly collapsed," says Seidler. "It really is a miracle," he says, "that it finally happened."

The serendipitous details underscore just how tenuous the path to the multiple awards and nominations has been. The young assistant of an agent who became involved happened to live in Australia near Rush, and dropped the screenplay through his mail slot while she was home on holiday.

"Nothing happened for some six months," says Seidler, "so I decided it had been a bad move after all." But then Rush signed on to play the crucial role of Logue. The actor's commitment finally helped get the award-winning film made.

And now, after waiting nearly a lifetime to tell this story, Seidler has become, at age 73, the oldest writer signed to UTA, one of Hollywood's top talent agencies.

The film's success, however, has invited new challenges, says Major, who points out that biopics nearly always attract charges of historical inaccuracy. In this case, they range from suggestions that the film whitewashes Nazi sympathies on the part of the king all the way down to gripes about inaccuracies in selecting a kilt's tartan. Award season broadsides can hurt a film's chances, concedes Major. In 1989, for instance, allegations that the front-runner film, "Mississippi Burning," did not do justice to the real events of the civil rights era "sank the film's chances," he says, adding that "Rain Man" subsequently overtook the historical drama for best film. What is so often overlooked in debates over historical accuracy in drama is the fact that these films are not documentaries. "They are spiritual representations of a time and the deeper lessons of history," Major says.

Deeply personal engagement is nearly always the key to successfully transmitting those lessons, says Mary Dalton, codirector of the Documentary Film project at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C. "There is a two-fold reason 'personal passion projects' are sometimes particularly memorable. First, the filmmaker's personal connection to a story can imbue it with indelible authenticity," she writes in an e-mail. Second, she notes, that same passion can sustain the commitment necessary to get a picture made in an industry where it can take years and years to take a project from concept to completion.

Yet these offbeat films that challenge official history or industry conventions are the lifeblood of truly creative filmmaking, says Gordon Coonfield, an associate professor of film and media at Villanova University in Philadelphia. But the entertainment industry's growing dependence on blockbusters make it deeply risk-averse, he points out.

"It's a vicious spiral downward," he says. "And it results in a decreased tolerance for creativity, for risk, for something different but potentially beautiful. As a consequence, great films go unmade and unwatched. Still, occasionally films like this one slip through and, hopefully, awaken something that the next sequel-to-a-formula [film] won't be able to put to sleep again."