Appreciation: the lyrical works of an Indian master

Loading...

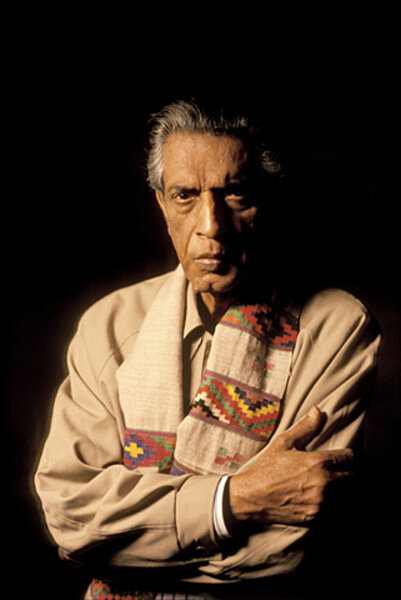

In 1992, the great Indian director Satyajit Ray, in rapidly declining health but characteristically gracious, received an honorary Academy Award while in his hospital bed as all the world looked on. He died soon afterward.

Because it became apparent to the academy at that time that many of Ray’s films were in dire need of preservation, the Academy Film Archive’s Satyajit Ray Preservation Project, in collaboration with the National Archives of India; the Satyajit Ray Film and Study Center at the University of California, Santa Cruz, founded by the indefatigable Dilip Basu; and several other foundations, was born. The ongoing goal is to preserve and restore all 28 of Ray’s feature films and seven short subjects and documentaries. Eighteen of those features, plus one short, have thus far been preserved. (The honor roll for this project includes David Shepard, Michael Friend, Michael Pogorzelski, and Josef Lindner.)

This is a cultural mission of the highest importance; beginning Sept. 6 with the first two films in “The Apu Trilogy” (the third screensSept. 9), audiences will have the rare opportunity to see on the big screen all 19 of the currently restored Ray films, first at the Samuel Goldwyn Theater in Beverly Hills and then continuing Sept. 21 through Oct. 21 at the American Cinematheque’s Aero Theatre in Santa Monica.

There is every expectation that these films will be screened in other cities. But if you are anywhere close to Los Angeles this fall, why wait? (In London, a restored Ray series is already in progress courtesy of BFI Southbank; in December and January, the Austrian Film Museum will be screening archive prints.) If you can’t make it to Los Angeles, know that many, though by no means all, of Ray’s best films are available on DVD, most recently two magnificent ones, “Charulata” and “The Big City,” both from Criterion.

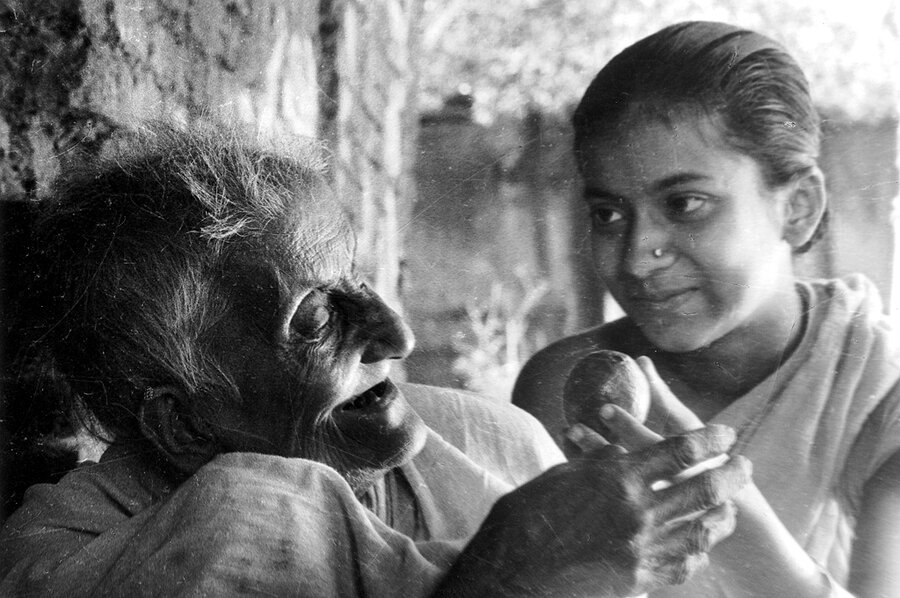

The point is that Ray’s films, however you get to them, must be seen. He is, for me, perhaps the greatest of all film artists. “The Apu Trilogy,” consisting of his first film, “Pather Panchali” (1955), “Aparajito” (1956), and “The World of Apu” (1958), is a humanistic epic like no other. The finest sustained artistic expression in film history, it follows a young boy from a poor Bengali village to his adulthood in Calcutta, and it seems to encompass everything there is to say about life and loss and redemption. (If you can get your hands on it, check out Ray’s marvelous book-length 1994 memoir, “My Years With Apu.”)

If Ray had only made this trilogy, he would have earned his place beside Jean Renoir, Vittorio De Sica, Yasujiro Ozu, Charlie Chaplin, and the D.W. Griffith who made “Broken Blossoms,” as one of film’s supreme humanists. But he has, by my count, made at least a half-dozen other masterpieces. To name names: “Devi,” “The Music Room,” “Charulata,” “Three Daughters” (my favorite of his films after the trilogy) – all of which have been restored – as well as “Days and Nights in the Forest” and “The Home and the World” (which have not).

And here is the most stunning thing: Of the 24 dramatic features of his that I’ve seen (I’ve missed four), there isn’t a bad one in the bunch. His consistency is unearthly.

Ray was a true national artist, and he presented to the world an India that was both vividly present and suffused with the ancient. (I traveled to Calcutta three years ago in connection with a Ray festival and was immediately struck by how deeply his movies captured his country’s past-in-the-presentness.)

For audiences inured to the turbo-charged rhythms of modern moviemaking, Ray’s films will seem slow – at first. But the lyrical meditativeness of his movies, like Ozu’s, is a taste well worth acquiring.

No other director is as preternaturally aware of the seasons, of nature, of the simple human gesture that opens up worlds. No director had a greater psychological comprehension of people, of children. No one created better roles for women, or explored their mysteries so resoundingly. No other director could make the everyday so sensuous and ineffable.

The ongoing celebration of Ray’s films is, in the truest sense, a celebration of the power of the film medium itself. Ray grasped this power more than any other film artist. Movies don’t often change your life. His will.