'The Red Turtle' has a quietly breathtaking delicacy

The delicacy of the animated movie “The Red Turtle,” which is directed by the Oscar-winning Dutch-British illustrator and animator Michael Dudok de Wit, is so quietly breathtaking that to call it a tone poem doesn’t quite do the film justice. This is the first international co-production of Japan’s famed Studio Ghibli, and in its hushed evocation of nature’s mystic mysteries, it summons at its best the work of the studio’s founders, Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata. But Dudok de Wit’s sense of form and color is even more minimalist than the work of those masters. Ten years in the making, “The Red Turtle” is both homage and sui generis.

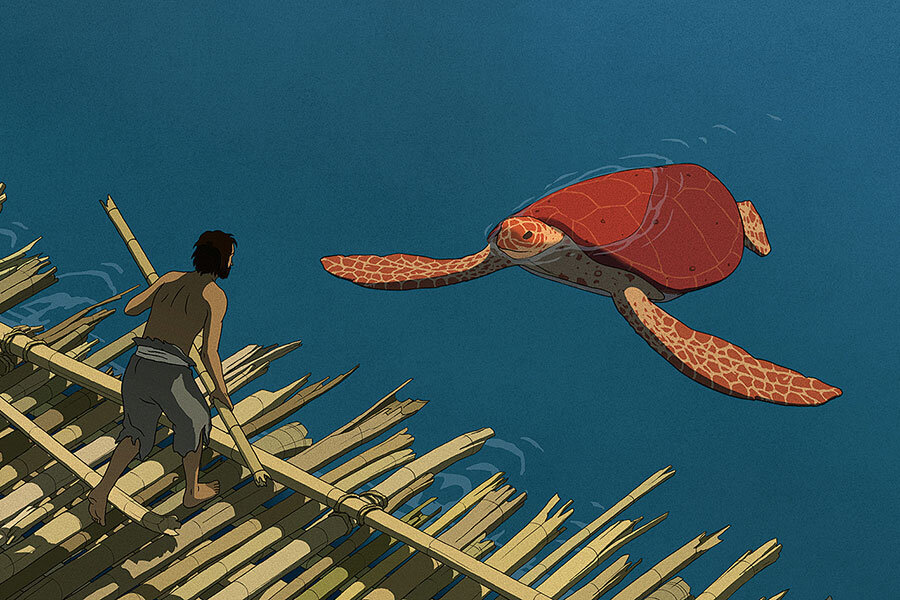

The film begins with a shipwreck in which a passenger – a sailor, perhaps – is violently swept ashore a deserted tropical island in the watery middle of nowhere. His frantic attempts to build a raft from bamboo logs continually come to naught because every time he casts off, a large sea creature – as we soon learn, a gigantic turtle with a bright red shell – splinters the conveyance to smithereens.

The red turtle does not seem malevolent, just persistent. There is a reason it wants the man to remain on the island, and, after exacting his revenge on the turtle, the film moves ever more decisively into transcendent realms of fantasy. The transformation of the turtle into the beautiful young woman who will become the man’s mate is as satisfying as anything in a Hans Christian Andersen fable.

This transformation is doubly welcoming because, up until this point, Dudok de Wit has achingly evoked the man’s deep, spooky aloneness. We’ve seen this situation before, from “Robinson Crusoe” to “Cast Away,” but more than almost any other film I’ve ever seen, “The Red Turtle,” which is entirely wordless, expresses the isolation of being forbiddingly alone with nature. (The soundtrack is vibrant with the rush of wind and water and birds.)

With its lush greens and barren beaches, the island is teeming with tiny sand crabs that scurry sideways, like little windup sentries. The ocean is flush with creatures that are like underwater emissaries from some aqueous kingdom. When the man looks up at a starry night sky and hallucinates seeing a string quartet playing on the moonlit beach, he is swooned by both the beauty and the terrors of his predicament.

Dudok de Wit and his co-writer, Pascale Ferran, don’t sentimentalize the man’s predicament, even after he and his wife have a playful baby boy. The dangers of the island – the rocky crevices from which one can slip from great heights into near-inescapable pits – are ever-present. And because we have witnessed the transformation of the red turtle into the red-haired woman, we are always aware that the story carries a fantastical dimension.

We wait to see how it plays out. The film may run only 80 minutes, but it seems longer – and I mean that in a good way. Shots of the island are often held for their own sweet sake, to let the stillness of the mood sink in. The people are often filmed from very high angles in order to emphasize their insignificance in nature’s grand scheme. When something explosively dramatic occurs, such as a tsunami that wipes out much of the island, it’s as if paradise itself had been despoiled.

But this paradise was never halcyon – this is no “Blue Lagoon.” Behind even the movie’s most transcendent tableaux is the lurking fear that this communion will vanish as decisively as it arose. Perhaps this is why Dudok de Wit has chosen for so much of his film a grayish palette inspired by Japanese ink and watercolor prints. He wants the look of the film to have a ghostly evanescence, and what’s remarkable is how, utilizing such a minimal color scheme, he is able to convey such beauty.

“The Red Turtle,” a rare “children’s film” that works equally well for adults, doesn’t have the easily definable meanings that often attach to classic fairy tales. At times, it can seem overly elusive, starting with its main character – a man with unplaceable origins who, from first to last, is a blank slate. But as I eased into the film’s hypnotic swing, this ambiguousness became more and not less attractive. “The Red Turtle” benefits from being open to all sorts of possibilities and interpretations because we sense that Dudok de Wit respects our imaginings. He allows them to take shape right alongside his own. Grade: A (Rated PG for some thematic elements and peril.)