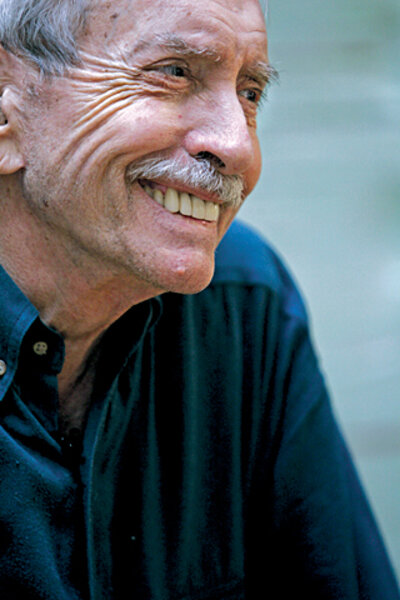

Edward Albee: American playwright's goal is to stir humans to change

Loading...

In 30 plays over half a century, Edward Albee has outraged, engaged, entertained, and puzzled – some would say baffled – the public. The octogenarian playwright hopes he has also prodded his audience to think about issues that matter. The legendary actress Elizabeth Ashley, starring in Albee's latest play, "Me, Myself and I," (at Playwrights Horizons theater in New York City from Sept. 12 to Oct. 10), calls him "one of the great artist-warriors" and "a hero of humanity" who is "fighting for that which is most valuable in civilization."

Although lauded as the conscience of the American theater, Albee doesn't create hortatory, agitprop dramas as were popular during the Depression. Popularity has never been his problem; many plays have been deemed impenetrable, overly cerebral experiments. After his 1983 play "The Man with Three Arms" was roundly denounced (a Variety critic calling it "an intolerable audience ordeal"), no new, full-length plays by Albee appeared in New York for a decade.

During this partial eclipse, Albee kept speaking out for artistic freedom, teaching at the University of Houston, and writing plays, which were produced in regional theaters and Europe.

Not until 1993-94, when the Off-Broadway Signature Theater Company devoted its season to his work and the Pulitzer Prize-winning "Three Tall Women" was performed in New York, was his reputation resuscitated. Now he's acclaimed as America's preeminent living playwright, a testament to perseverance and refusal to compromise one's vision.

Rebirth in rebellion

Emily Mann, director of the new play and artistic director of Princeton's McCarter Theatre, calls Albee "one of the true greats" in the pantheon of dramatists, rating his work "at the very top" of world dramatic literature of the 20th and 21st centuries. The accolades are impressive: three Pulitzers (the others were for "A Delicate Balance" in 1967 and "Seascape" in 1975), three Tony Awards, and a 2005 Lifetime Achievement Tony Award.

On presenting Albee with the National Medal of Arts in 1996, President Bill Clinton paid tribute to him, saying, "In your rebellion, the American theater was reborn."

Ever since "Zoo Story" (1958) and his masterpiece "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?" (1962), Albee has been writing complex, complicated plays full of barbed dialogue. His works probe dysfunctional family dynamics and reveal moral and spiritual vacuity at the root of characters' complacency. He views drama as a catalyst for change, saying in a recent interview, "If a play is not socially useful, if it doesn't have content and make people think intelligently, it's a waste of time." He adds, "Plays hold a mirror up to us and show us how we're behaving and why we shouldn't [behave that way], and maybe we should learn how to behave better and more usefully."

Yet he adamantly denies writing plays with an overt message. His works – far from opaque but also far from simplistic – demand audience involvement to decipher their meanings. "My plays are accessible," Albee says, "if you wish to access them."

"That's what the mission of theater is," Ashley maintains: "to infiltrate the most dangerous, radical, unspeakable ideas into people's souls." She adds, "If you don't have anarchists and heretics intellectually, emotionally, psychologically, and artistically, all you have is the status quo, and we know what happens when the status quo is not challenged."

Newest play is 'existential vaudeville'

Albee has gleefully challenged the status quo throughout his career. His new play is no exception. A non-naturalistic, seriocomic play in which identical twins question their ties to their mother and to each other, it is, in Ms. Mann's words, "a dazzling linguistic piece with existential and theoretical mind games." Chuckles and guffaws escalate in the audience over the course of what Mann calls "existential vaudeville" and Ashley terms "slapstick heresy." According to Albee, "It's funny, except when it isn't" – that is, when its serious implications intrude.

Ashley plays a bigoted mother who refuses to see her 28-year-old twins as distinct individuals, repeatedly asking each one, "Who are you?" For her, the play is about "the myth of motherhood nuked," showing "the underbelly of motherhood, the truth that dare not speak its name."

Albee, a fiercely liberal patriot, doesn't shy away from placing blame for what he sees as America's increasingly "sick, troubled society," which he says is polarized by destructive politics and racial prejudice. In a rare moment of explicit analysis, he explains, "The problem with the country is represented by the mother in my play: totally selfish, totally irresponsible, badly educated, and badly informed, believing that what she believes is the truth."

Mann sees universal themes in the play, implied through one twin's quest for an independent, self-chosen identity instead of a persona imposed by heredity and upbringing. "It's a very human, family play," she says, with "enormous themes" that "chime all through the play": themes like leaving home, constructing an identity, and the gains and losses of separating from family.

The play questions the assumption, Albee says, "that what makes us comfortable is something we should want," and "that what we believe is necessarily right." "Safety last" would seem to be his motto, as he drives his characters to question their values rather than passively accept what they're told.

Although his concerns are coded in his plays, Albee speaks with urgency on the need for a vigilant, educated American public. "The whole future of the United States as a democracy is at stake," he says, which makes it imperative that artists "get people involved in responsible, informed political thought."

Although information is more readily available than ever through the Internet, the playwright fears "people don't read in depth anymore." He notes, "Information is nothing without understanding where it comes from, what led to it, what its consequences are. In other words, what it means."

As a longtime proponent of human rights with the international writers' organization PEN, Albee has spoken against censorship of dissidents in dictatorial, repressive societies elsewhere. Now, with America "trying to retreat into the past," he insists the focus should also be on problems here. In this regard, the current recession may offer an opportunity – as did the Depression – for Americans to rethink their priorities. "Economic calamity," according to Albee, "can quite often revitalize a society."

Striving for 'we' over 'I'

The twins in the play explore who they are as opposed to who it's safe to be and who they wish to be. Perhaps Americans can forge an identity greater than the narcissistic "me, myself, and I" and strive for the unified diversity of "we, the people," Albee suggests. As George (the character played by Richard Burton in the film version of "Virginia Woolf") says, "Truth and illusion. Who knows the difference, eh, toots?"

George also says, "That's for me to know and you to find out." Albee, ever the cryptic sphinx rather than a proselytizer in his plays, embeds what he believes to be true in characters that speak to us emotionally and intellectually. What they teach is for you to find out.