Levon Helm and The Band: a rock parable of fame, betrayal, and redemption

In the eight years preceding his death Thursday, Levon Helm enjoyed the highest distinction that any music veteran could hope for: an audience that remembers.

Three recent Grammy awards had brought a resurgence of interest in Mr. Helm’s career as the voice and drummer of The Band, one of rock’s most enduring groups. But it was only in 2004, when he began his homespun “Midnight Ramble” concerts, that he began to reemerge into the public eye following years of health and financial problems, as well as lingering disappointment and resentment surrounding the dissolution of his former band.

Indeed, much of Helm’s story is a parable of rock ‘n’ roll – the story of a band fractured by money and fame, leaving its disillusioned members to pick of the pieces of lives that had seemed to promise something more.

In that way, Helm’s musical legacy is not one meticulously groomed by publicists or biographers. It has evolved organically through what he has left behind.

His appeal in The Band and to Bob Dylan, who collaborated with the group during his most fruitful years, has not just been his voice but also his insurgent spirit. After all, the late-1960s marked the transition from presenting pop music as audible candy for teens to a progressive art form. While the Beatles represented a breakthrough in pushing boundaries that were heady and abstract, The Band later represented their American counterpart, which was dangerous, unkempt, and with a profound feel for, and understanding of, blues, gospel, and country.

That understanding came largely from Helm’s biography. The only American in a group of Canadians, he grew up in Turkey Scratch, Ark., as the son of cotton farmers. Many of the references in classic Band songs came from the people he knew and the sounds he heard in his childhood. Blues great Sonny Boy Williamson performed regularly in the area, and traveling minstrel shows and rockabilly bands made frequent stops.

Helm “couldn’t wait to get out of high school and get off the farm. His dad told him he couldn’t play with bands until he finished high school.… All he was doing was biding his time,” says Anna Lee Amsden, Helm’s lifelong friend and the “Anna Lee” in the lyrics of “The Weight,” the group’s classic song. “Crazy Chester” and “Carmen,” other familiar characters in the song, were also people Helm knew in town, Ms. Amsden says.

In a statement Friday, Mr. Dylan called Helm "one of the last true great spirits of my or any other generation."

Much of The Band’s identity – as suggested by its name – was in being a true collective where no single person stood out. The Band’s 1968 debut, “Music From Big Pink,” reflected that unity. Despite vocals shared by Helm, Richard Manuel, and Rick Danko, no one singer was identified, and the lyrics weren’t even printed on the jacket. The magic of that music came from a special alchemy among those individuals that could never be achieved separately since.

Yet in what is now a storied pattern from the early days of the music business, camaraderie crumbled amid fame. In his autobiography “This Wheel’s On Fire,” Helm contends that Robbie Robertson, The Band’s lead guitarist, joined with the band’s management to persuade the others to sign away their individual publishing rights, which in today’s era of multiplatform media are considered the pension plans of the music industry. They ensure artists later income when the songs receive renewed life in movies, television, and beyond.

In his book, Helm describes seeing a copy of the 1969 album “The Band” and noticing he was credited for writing only half of one song, with Mr. Robertson credited on all 12.

“Someone had pencil-whipped us. It was an old tactic: divide and conquer,” he writes.

Things got worse in 1978 when director Martin Scorsese, who collaborated with Robertson on the film “The Last Waltz,” reinforced what Helm said was a false narrative that Robertson was somehow the band’s auteur.

The long-term damage had been done by the time Helm reunited with his bandmates minus Robertson in the 1980s. Despite their acclaimed musicianship, the group was relegated to the oldies circuit and money did not come steadily. Mr. Manuel hung himself in a hotel room while on tour in 1986. Helm pulled his body down and never fully recovered.

Mr. Danko died 12 years later, suffering various health complications. A month before Danko’s death, I watched him play to a half-empty Chicago-area music room. While his signature voice remained angelic, he looked tired and seemingly not deserving of such meager surroundings considering the hugely influential body of work he created with The Band.

In his book, Helm blamed Robertson and his former business partners for Danko’s condition. “If Rick’s money wasn’t in their pockets, I don’t think Rick would have died because Rick worked himself to death.… He wasn’t that old and he wasn’t that sick. He just worked himself to death. And the reason Rick had to work all the time was because he’d been [expletive] out of his money.”

Helm eventually insulated himself in Woodstock, N.Y., and declared bankruptcy following a house fire that destroyed his possessions and put him into debt. But in 2004, with the help of town locals, he started hosting Saturday night concerts at his new home.

The concerts were underground affairs until a New York Times article broke the news and soon, the weekly events became regular sellouts, which led to touring, larger audiences, and his first solo album in 25 years. In 2007, he emerged from bankruptcy.

The phenomenon of the “Midnight Ramble,” as Helm called the Saturday evening house parties, reflected Helm’s unique downhome sensibilities. At one performance I attended while on assignment for a music magazine, his house on a pitch-dark wooded back road was marked by a balloon tied to a mailbox. There, the road opened to a large field for parking. Tables set up by town locals had cupcakes, cookies, juice, pasta salad, and other food. People mingled and talked while Helm’s dog, Muddy, wandered around looking for ear scratches.

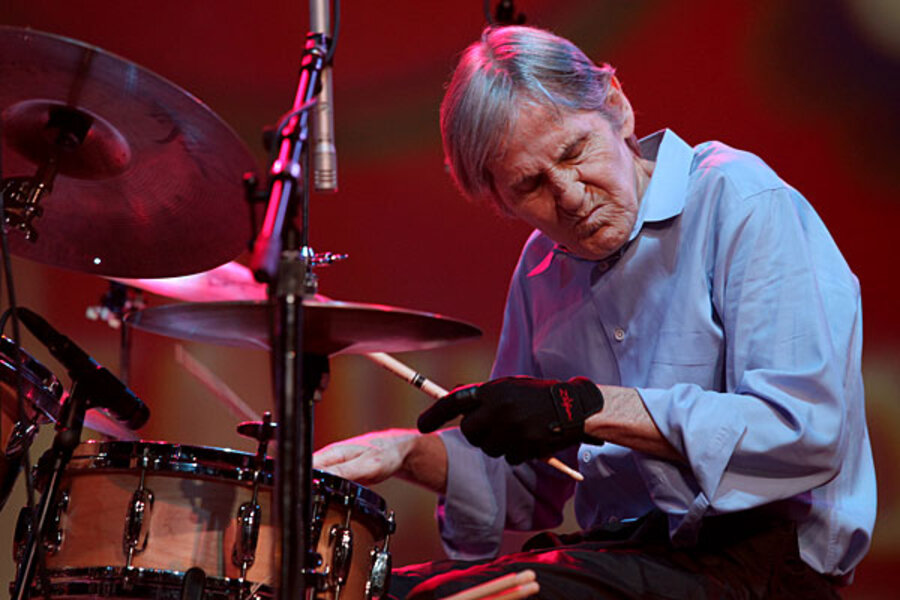

When it came time for the music, Helm emerged from a back room gleaming, shaking hands with the 100 people tucked around the room on folding chairs. Despite his age – and persistent throat troubles – he snapped at the drums with fierce strength while singing with emotive depth and tender inflections.

“It’s certainly a miracle for me and a dream come true. I never thought I would sing and play like I used to be able to do. I thank God. Every song is a celebration for me,” he said at the time.

At that time, the setlist comprised mainly of blues, Cajun, and Southern soul classics. But by the time Helm was playing to sell-out crowds on the theater circuit and to younger fans at festivals like Bonnaroo in central Tennessee, he acquiesced and performed more familiar Band fare, now accompanied by a band consisting of his daughter, family friends, and the occasional all-star guest like Elvis Costello or Emmylou Harris.

Like any music that remains long after the people who created it have moved on, The Band’s songs remain mysterious, much like the photographs from that era that showed them wearing saloon-keeper suits and gunslinger headwear, making them look like the images from the Civil War-era, not Vietnam.

That timeless sound, like photographs we receive from the people before us, is infused with a mixture of joy and sorrow.

At Helm’s home, I noticed two lit candles on a shelf. Helm later told me they were in memory of Danko and Manuel.

“We got some good spirits with us every day,” he said.