Fossils found in South Africa point to early human ancestors

Loading...

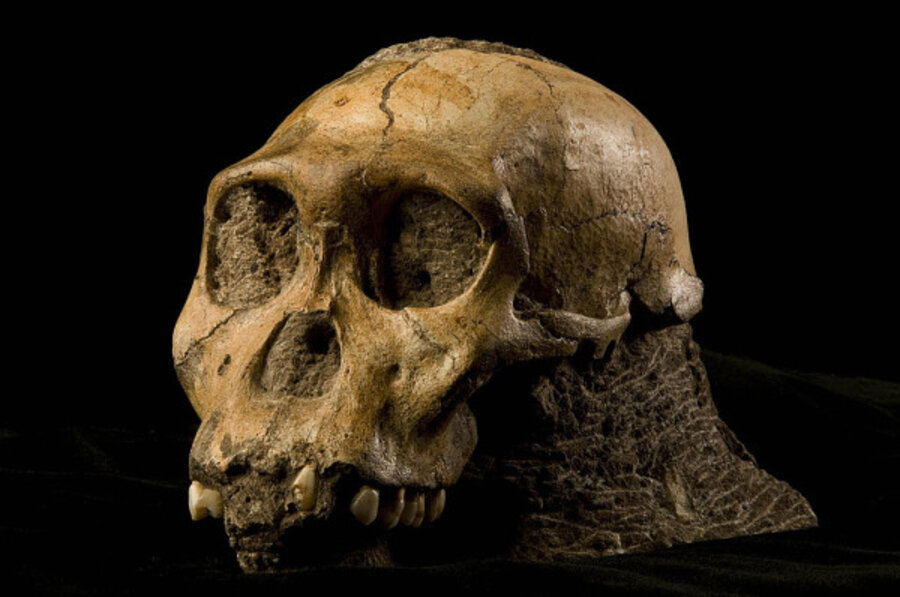

The eroded remains of a prehistoric limestone cave in South Africa have yielded fossils belonging to a new species of early human ancestor, an international research team announced Thursday.

Two sets of fossils, dated to around 1.95 million years ago, belonged to a female in her late 20s and a male 12 years old. They were found in a hilly area near Johannesburg known for its early human fossils.

The purported new species, Australopithecus sediba, "may make a very good candidate ancestor" to the genus Homo, which includes modern humans, says Lee Berger, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, who led a team that found the fossils. "Sediba might be a Rosetta Stone for defining for the first time just what the genus Homo is."

The researchers estimate that the individuals were roughly 4 to 4-1/2 feet tall. They sported long, ape-like arms with small, powerful hands, indicating that they still frequently used trees for protection. But hip bones associated with both individuals are human-like, indicating that they were competent upright walkers.

Unique combination of features

The partial skeletons the team found "have a combination of features that we have not seen before," says Rick Potts, a paleoanthropologist and director of the human-origins program at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History in Washington.

Yet he adds that it's a bit early to label the find a new species. The discovery represents a single snapshot in time, so it's unclear if the individuals the team found represent the tip of a dead-end branch of Australopithecus, or something truly along the direct line from Australopithecus to Homo.

Still, the find is remarkable on several levels, researchers say, all the more so because this is a poorly represented time period in the fossil record for early humans. The bones are exceptionally well preserved compared with many other early-human fossils found in Africa.

Moreover, many finds come as disparate bones. The fossils from the two new individuals include skeletal segments that remain connected – portions of a hand to a forearm for instance, or a complete upper arm and forearm. That makes it easier to spot features that help researchers place the species in the broader context of human evolution.

Site contains well-preserved animals too

And the site contains equally well-preserved remains of saber-tooth cats, mice, wild dogs and cats, hyenas, and horses, putting the new hominins in a broader environmental context.

The fossils were discovered 18 months ago, when Dr. Berger and colleague Paul Dirks were combining the power of Google Earth and traditional aerial photographs to map the known caves and fossil finds at the UN-designated Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site near Johannesburg. This site contains the spot where the team found the new individuals.

During a visit to the site where the fossils were found, Dr. Berger had brought his nine-year old son Matthew and another colleague. Berger had been to the spot a few months earlier and recognized its potential for finds. So he turned his son and colleague loose to see if they could find any fossils on the surface.

Matthew immediately ran off the immediate site and with within a minute said, "Dad, I found a fossil," Berger recalls. Fortunately, Matthew found it before their dog Pal, who also was at the site. The fossil turned out to be the collar bone of one of the two individuals described in the Friday issue of the journal Science.

The remarkable state of fossil preservation resulted from the cave system that the researchers say the individuals happened upon, adds Dr. Dirks, a geologist at James Cook University in Townsville, Australia.

Did they fall into a cave?

The limestone caves in the region often sport vertical shafts that drop from the surface to the cave ceiling. The team surmises that the two individuals, along with many animals, may have fallen into the cave through one of these shafts, drawn to the drop either by the prospect of water or the smell of a potential meal.

The isolation prevented scavengers from breaking up and scattering the remains. Debris flowing through the cave, perhaps driven by an intense rain storm, deposited the remains into an oversize pothole in a lower level of the cave and covered them with sediment.

"They fossilized quickly," Dirks says.

A million years of erosion eventually exposed the roughly six-foot-deep pothole.

The team has found the remains of at least two more individuals at the site, along with a treasure trove of evidence about the environment they inhabited.

Regardless of where these new individuals eventually come to rest on the evolutionary tree, "we have one of the most remarkable records, even with two individuals, a male and a female, an adult and a juvenile, of a single definitive species in the same time space," Berger says.

Whatever their place on the evolutionary tree, he adds, "they are going to be a remarkable window, a time machine, on the evolutionary processes and evolutionary stresses going on between 1.8 and 2 million years ago."