US tax bite smaller than other nations'

Loading...

As millions of Americans file their tax returns this month, they can find some solace in comparing US tax rates with those in other nations. Or can they?

The United States still has a lower overall tax burden than the typical advanced economy in Europe. But the gap isn't as big as you might think, and it may be poised to shrink as the pace of federal spending ticks upward. Here's a look at how Americans' tax burden ranks against that of citizens of other countries, and why it matters.

How do US tax rates compare with those in other nations?

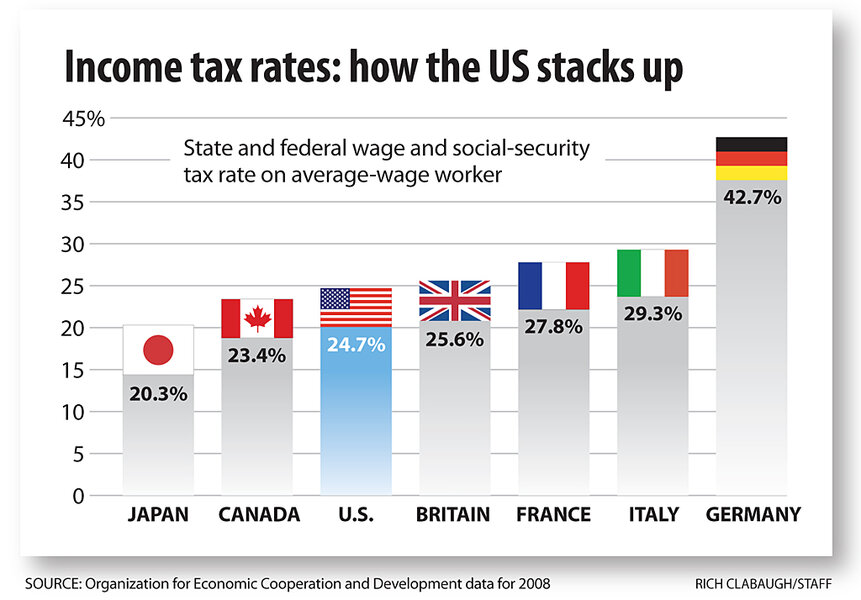

The average American pays wage-based taxes that are similar to what Britons pay – and not much lower than in France. Japanese citizens enjoy the lowest rates among the Group of Seven large industrial economies, or G-7. This includes national and local income taxes, plus payroll levies such as the employee share of Social Security.

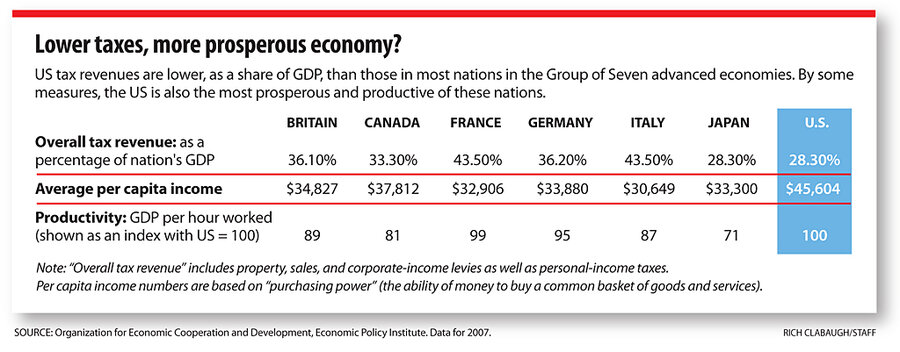

But wage and payroll taxes are just part of the picture. Add in sales taxes, capital gains taxes, property taxes, and corporate taxes, and the US sends 28 cents of every dollar of output to the government. That still matches Japan for the lowest ratio of tax revenue to gross domestic product (GDP) among the G-7 nations. France and Italy score highest.

Why is tax policy important now, and why view it globally?

The US is headed toward what finance experts have bluntly called a "fiscal train wreck." If uncorrected, current trends would force the government to spend a growing amount to service the national debt. That debt burden, or the tax hikes that might occur because of it, could slow economic growth substantially.

Other nations can offer some lessons. The recent pressure on Greece to impose austerity measures is a reminder of the perils of deficit spending. The US and other G-7 nations don't face an imminent boycott by bond investors, but they have retiree-entitlement burdens and rising debt.

"We're looking more and more like European nations," says Rosanne Altshuler of the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center in Washington.

Another message from a global comparison: The US has the advantage of addressing the challenge from a starting point of relative prosperity. The US tops the G-7 list in average income.

What is President Obama doing about tax policy?

He has pledged not to raise taxes on Americans with household incomes below $250,000. But with an eye on the budget challenge ahead, he's also created a tax-policy panel and a bipartisan fiscal commission.

The goal is to bring budget deficits down to 3 percent of GDP or less. (The Obama administration argues that this, coupled with the natural growth of the economy, would essentially keep the national debt from growing larger as a percentage of GDP.)

It won't be easy to hit that target. Mr. Obama has already leaned heavily on one revenue-raising option – hiking taxes on high-earning households – to pay for healthcare reform.

Now he needs a plan that goes beyond more tax hikes on the rich. (It would require a tax rate of 77 percent on top earners, by Ms. Altshuler's estimate, for a tax-the-rich strategy to reach Obama's deficit target.)

How can America put its government finances in order?

The three main options are reduce the growth rate of spending, obtain more tax revenue, and seek the fastest growth rate for the economy (on which tax future revenues will be based). How to blend those strategies is a matter of hot debate, with conservatives emphasizing the risk that higher taxes will crimp economic growth.

Daniel Mitchell, a tax expert at the libertarian Cato Institute, favors spending restraint and efforts to boost economic growth through a simpler, more efficient tax code. "The international comparisons are instructive," he says. Fiscal quagmires are "all about too much government spending," which then puts upward pressure on tax rates.

Other fiscal experts say more tax revenue is needed (along with spending curbs), and that modest tax hikes won't have an adverse effect on the economy. Looking abroad, they see the value-added tax, akin to a sales tax, as an effective approach. Another option is to boost existing taxes, such as on income.

Finally, there's tax reform – simplifying the current maze of deductions and credits. Done well, it could reap gains in tax revenue, fairness, and economic performance. But as Americans know, politicians like to tinker with the tax code more than they like to reduce its complexity.