Airlines: First it was the baggage fees. What’s next? Pay toilets?

Loading...

| Los Angeles

With the busy summer travel season just ahead, airline passengers are asking: Where will the surcharges end?

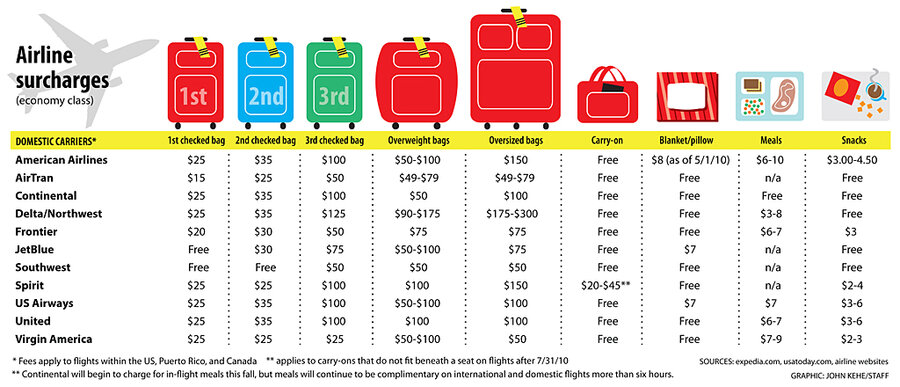

Most airlines now charge for checked luggage, which once was transported for free. Some now ask $8 for a tiny pillow and a thin blanket that barely covers your knees. Meals in economy class are mostly a distant memory. Are airlines planning additional surcharges, or might passengers revolt against more and more fees?

How much extra money do airlines make on surcharges?

Ancillary revenues, as the airline industry prefers to call them, are big moneymakers. They generate hundreds of millions of dollars for the beleaguered carriers, says Seth Kaplan, managing partner of Airline Weekly. For example, American Airlines alone made close to $300 million from surcharges in 2009.

Industrywide, income from the new a la carte charges – slapped on everything from checked bags to boxed snacks and changed reservations – hovers in the $7 billion to $10 billion range, writes Allison Danziger of TripAdvisor in an e-mail.

These fees now make up roughly 20 percent of the industry’s revenues, adds Bill Miller, senior vice president of CheapOair.

Have fares themselves stayed relatively flat?

The simple answer is, sort of but not really, according to Mr. Miller. Despite airline claims that “unbundling” fees from base fares will benefit customers, the reality is that they probably don’t.

While fares are generally lower now than in the past after adjusting for inflation – up to 15 percent lower over the past 15 years, he says – the extra charges are pushing the total bill ever higher.

For instance, a $300 ticket to Chicago in 1995 might cost $290 today. “But,” Miller adds, “now you’re probably paying for the first bag to be checked, certainly for onboard food, and maybe Wi-Fi in the air, all of which add up to more than the “old, ‘bundled’ price tag of yesterday.”

Does any airline have no surcharges?

You’d be hard-pressed to find an airline that doesn’t charge any fees for amenities or checked baggage, says Ms. Danziger, although there are differences among carriers.

Southwest Airlines, for instance, doesn’t charge for the first two checked bags, and JetBlue doesn’t charge for the first.

But, she points out, Southwest has tried to find creative ways to raise additional revenue. Last fall, the airline announced a $10 charge to allow customers to board the plane before their fellow travelers.

Do foreign airlines charge these fees for their domestic travelers?

Ultralow-cost international carriers such as Ryanair have led the way for their US counterparts, says Miller. Still, he points out, the Irish carrier makes its a la carte charges clear upfront: “If you log onto the Ryanair website, all these charges [from seat choice to checked bags] are in the purchase process now. This eliminates the irritating experience many passengers face today of arriving at the airport with a ticket in hand only to face new charges just to get on the plane.”

The carrier is also smart about capitalizing on addressing small things that annoy customers. For one euro (about $1.35), it will send a text message to notify customers of flight changes or whether their flight is on time.

What will airlines charge for next?

Possibilities range from a fee to preselect a seat and a small onboard charge to use the lavatory – a proposal already floated by Ryanair for its flights under an hour – to a charge for bringing an infant on board.

“Airlines have been bleeding money,” notes veteran pilot Karen Kahn. She knows that consumers are unhappy with being charged for what they used to get for free.

But, she points out, air travel is a very competitive business, and companies are in a scramble to differentiate themselves from one another. Have a complaint? Speak up, she says. “This is a very passenger-driven business.”