Immigration debate: fight brewing between ACLU and Nebraska town

Loading...

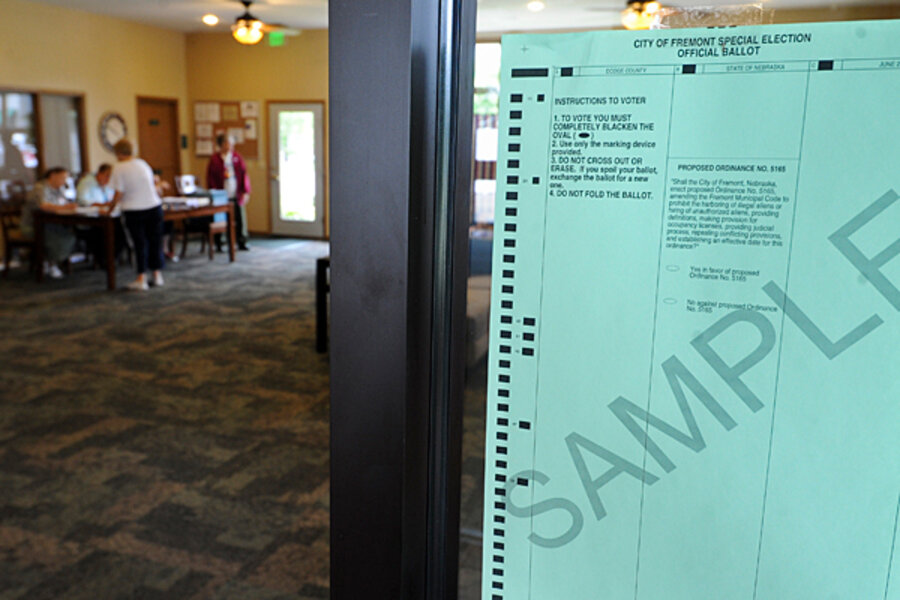

Immigration debate in Fremont, Neb., has made it the latest town to decide to take immigration enforcement into its own hands.

On Monday, 57 percent of voters in the 25,000-person town in eastern Nebraska helped pass a law that would bar businesses from hiring illegal immigrants or landlords from renting to them.

In doing so, it joins Hazelton, Pa.; Riverside, N.J.; Valley Park, Mo.; and at least a few dozen other towns that have passed laws targeting undocumented immigrants. The ordinances have generally faced lawsuits, and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in Nebraska has already declared its intention to fight the Fremont bill.

“An ordinance of this kind is a true indication of the frustration some communities feel, and I don’t belittle that feeling,” says Laurel Marsh, executive director of ACLU Nebraska. “That being said, I believe it violates the supremacy clause of the United States.”

Ms. Marsh argues that two main problems exist with the law: that setting immigration policy is solely a federal function, and that the 14th Amendment guarantees due process to all people in the US, not just citizens.

And so far, many cities – including ones like Hazelton and Farmers Branch, Tex., which have tried to restrict landlords' abilities to rent to illegal immigrants – have had laws struck down by federal courts, though they remain on appeal.

Legal costs

The cost of fighting such lawsuits has also caused some communities – like Riverside, N.J. – to drop the measures, and was a major argument of those in

Fremont who opposed the referendum.

"In a community of 25,000, it's going to be hard to take on the whole country, and it will be costly to do so," Fremont City Councilman Scott Getzschman told the Associated Press.

But such laws continue to crop up in communities around the country – a measure, say many, of the frustration that many Americans feel with the lack of federal immigration enforcement and with the burdens illegal immigration places on their towns.

“The feds aren’t doing their job,” says Mark Krikorian, executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies, which advocates restricting immigration. “It’s a sign of the public frustration, and you’re going to see more and more of this sort of thing.”

Those on the other side of the immigration debate agree with that basic assessment, and say that they hope that measures like Fremont’s, as well as the law passed in Arizona last month, will spur Congress to again take up the issue.

“You have Republicans who would rather stand in the way of changes that the public is demanding to federal immigration policy, and therefore allow towns like Fremont to take matters into their own hands, which does nothing to solve the problem,” says Ali Noorani, executive director of the National Immigration Forum, an immigrant advocacy organization.

Such ordinances are dangerous, he says, since “they lead to discrimination of people who look or sound like immigrants.”

How Fremont got here

In Fremont, the city council actually first took up the proposal two years ago, but it was defeated after the mayor cast a tiebreaking vote against the law, saying he believed that legally, such bans were only enforceable by the federal government. Outraged residents gathered enough petition signatures to put the issue to a vote.

As with many of the towns that have passed anti-immigrant laws, Fremont has seen an influx of immigrants in recent years, with a Hispanic population that has grown to about 2,000 people (up from less than 200 in 1990), many of whom work at nearby meatpacking plants.

Under the new law, prospective tenants would be required to apply for a license from the city and to document that they’re in the country legally. Employers would be required to use the federal E-Verify database to ensure they don’t hire an undocumented immigrant.

Despite the fact that similar measures have been struck down by other courts, the legal challenges are on far from solid ground, says Michael Hethmon, general counsel for the Immigration Reform Law Institute, which helped write the law that has been the model for Fremont and other cities.

He points to the fact that the law in Valley Park – which included the employer part of the Fremont law – was upheld by a federal circuit court.

In particular, Mr. Hethmon rejects the notion that the 14th Amendment would make such laws unconstitutional.

“This is a huge constitutional crisis,” he says. “It involves the meaning of citizenship and who gets to decide it.”

Related: