Thomas Jefferson a closet royalist? Hardly.

Loading...

| Atlanta

Quill pen in hand, Thomas Jefferson invited the King's noose when he set out to write what his fellow founders at first thought would be a mundane legal document: a declaration of independence from the British crown.

But despite a preamble that became a paean to individual liberty that has rivaled the Magna Carta in the breadth of its global impact, Mr. Jefferson apparently committed a slip of the pen.

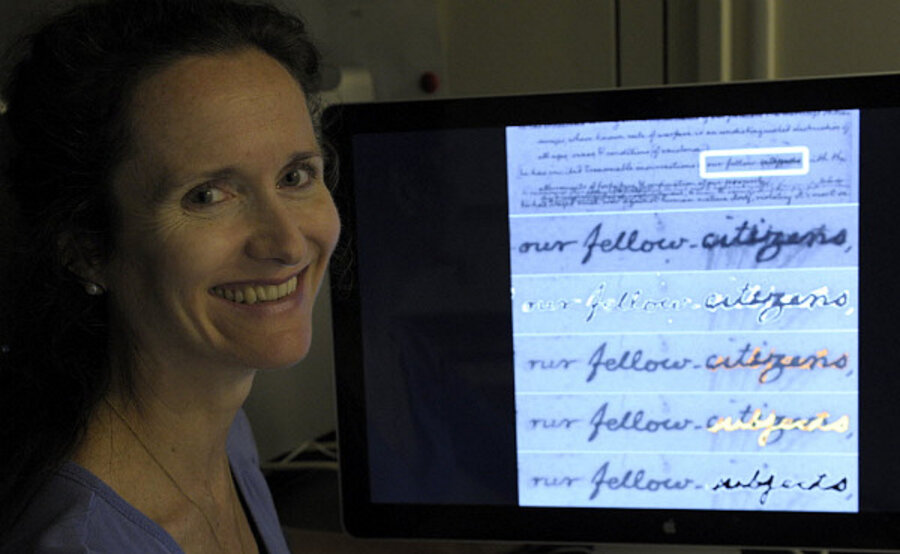

To usher in the Fourth of July weekend, the Library of Congress revealed hard evidence from high-resolution spectral imaging that Jefferson, on the third page of a "rough draught," wiped the word "subjects" off with his hand and meticulously etched the word "citizens" on top – perhaps the kind of brain-freeze that a modern writer quickly hits delete to send into the digital ether, but that Jefferson struggled mightily to erase in a section on British abuses of the Colonists.

Rough drafts of history

Declaration drafts are littered with strike-throughs and corrections, but the "subjects" mistake is the only one completely obliterated by a Founder.

Jefferson's original line read: "[The British government] has incited treasonable insurrections in our fellow-subjects, with the allurements of forfeiture & confiscation of our property."

(The finding, though confirmed by spectral imaging, isn't really new. A 2004 Princeton University paper makes note of the correction as part of a long list of rewrites made during the humid month-long session of the Continental Congress in Philadelphia.)

For a man who railed for individual liberty while keeping over 200 slaves at his Virginia estate, the slip also hints at "The Sage of Monticello" struggling to resolve the revolutionary social and cultural changes in the late 18th century and shows, in the blotting of fresh ink, the resolve needed to break from European patriarchal politics.

"It actually may represent a dawning in the mind of Jefferson, mid-sentence, that with this document the whole relationship between individuals and government is turned on its head from what had been accepted for thousands of years before," writes commenter “An American Expatriate” on the conservative Free Republic website. "For an historian this is like an astronomer seeing a snapshot of the Big Bang."

Were Americans 'subjects' or 'citizens'?

The philosophical difference between "subjects" and "citizens" indeed defined the Declaration of Independence, making the correction that much more intriguing to historians.

"It's almost like we can see him write 'subjects' and then quickly decide that's not what he wanted to say at all, that he didn't even want a record of it," said Library of Congress preservation director Dianne van der Reyden on Friday. "Really, it sends chills down the spine."

The father of republicanism and a staunch supporter of states' rights (and low taxes), Jefferson may indeed have made a Freudian slip, an unintended revelation of one's actual feelings. Jefferson, after all, burned his most private correspondence upon the death of his wife, Martha.

On the other hand, Jefferson was also simply stating a fact. At the time of writing, Jefferson and his fellow not-yet-Americans were, in fact, still subjects of King George.

Most likely, however, Jefferson lifted the word "subjects" from the First Virginia Constitution, which also refers to "our fellow subjects." (Jefferson was a habitual cutter-and-paster, borrowing, among other things, John Locke's phrase "life, liberty and property" for his famous "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness" line.)

The Declaration of Independence, of course, was a crowd-sourced entreaty, modified, cut and embellished by John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, among others, not always to the liking of Jefferson.

The subject-citizen transposition, however, is Jefferson's alone, researchers say.

For some insight into how the Declaration was really written, see Peter Stone's 1972 musical "1776.”

Related:

On July 4, the Founders didn't create America; America created the Founders