Causes of the financial crisis? Commission ends in hung jury.

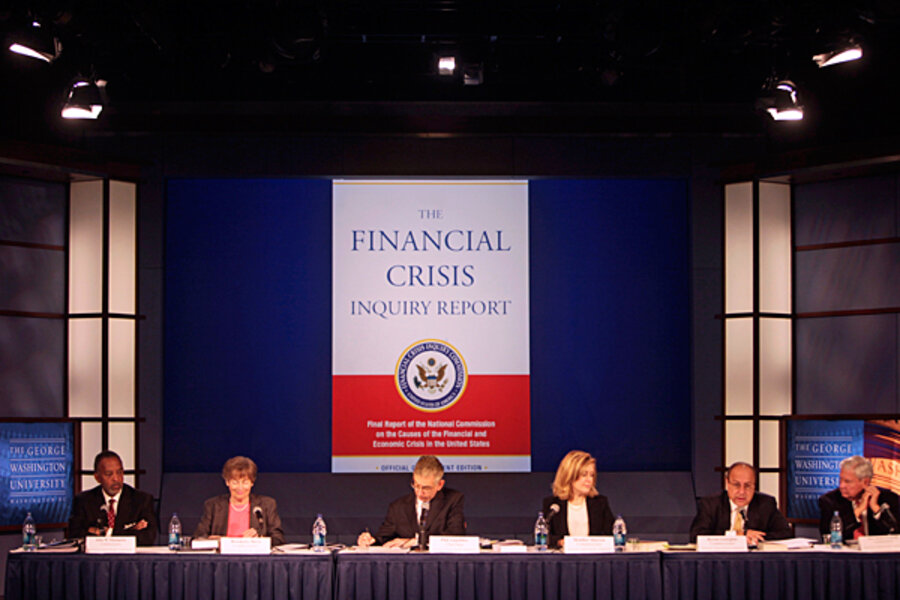

A commission exploring the causes of America's financial crisis has offered what may be the most detailed narrative yet of the events that plunged mortgages into foreclosure, the world into recession, and millions of US workers into unemployment.

But for all its rich detail, don't expect the 662-page federal report to settle the debate over what caused the panic.

Even within its own final report, the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission offers three views of the crisis -– one from Democrats and two dissenting views by Republicans on the panel, which was created by Congress.

The report would have carried more clout had the panel members been able to reach a unified conclusion. But that doesn't mean the 10-member commission has been unhelpful or that its varying conclusions will lack influence. Consider this alone: As part of its efforts, the commission has interrogated 700 witnesses including key figures in the crisis, from bankers to officials of the US Treasury and Federal Reserve, and put their views on public record.

The commission also was methodical: At the behest of Congress, it explored 22 possible root factors that may have contributed to the financial troubles that erupted in 2007 and 2008.

"Ours has been a journey of revelation," commission chairman Phil Angelides and other Democratic members said in the main body of the report. "Our major findings and conclusions ... are offered with the hope that lessons may be learned to help avoid future catastrophe."

The conclusions backed by Mr. Angelides and his colleagues portray a collection of factors that together set the stage for a calamity. In their view, many of the causes fall within two broad categories: lax government regulation and supervision of mortgage markets and financial firms, and private-sector greed unchecked by prudent risk management.

"The captains of finance and the public stewards of our financial system ignored warnings and failed to question, understand, and manage evolving risks within a system essential to the well-being of the American public," the report concludes. "While the business cycle cannot be repealed, a crisis of this magnitude need not have occurred."

The Democratic main report also prominently rejected several theories.

The writers hold that "excess liquidity" (including loose monetary policy by the Federal Reserve) was not a major precipitator of the crisis. Neither, they argue, should much blame be laid at the feet of the federally created mortgage agencies (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) or on more-general federal efforts to promote homeownership.

Beyond its broad conclusions is the report's trove of narrative detail. It recounts efforts back in 2002 by one Fed official (the late Edward Gramlich) to combat what he called "increasing reports of abusive, unethical and in some cases, illegal, lending practices.”

And it tells how in 2003, Prentiss Cox, then a Minnesota assistant attorney general, found a suspicious pattern in which mortgages by one lender were repeatedly written to people listed as "antiques dealers."

But Republicans couldn't buy into the main conclusions of the report, in part because they were so sweeping and general.

"The majority’s ... report is more an account of bad events than a focused explanation of what happened and why. When everything is important, nothing is," commission members Keith Hennessey, Douglas Holtz-Eakin, and Bill Thomas write in their joint dissent.

Their analysis doesn't reject the factors cited by Democrats entirely. They see poor risk management by firms as a major factor, and they allow some role for poor regulatory oversight.

But the three Republicans lay out their own carefully traced chain of causation.

It started with a credit bubble, they argue, thus pulling to the forefront the issue of "excess liquidity" that the Democrats played down. Although traditional theory might expect such bubbles to be rooted in loose monetary policy by the Fed, they point to other forces as central: global flows of capital and the credit created by an evolving climate of risk taking in the finance industry.

The Republicans then cite follow-on events: a housing bubble, shoddy mortgage lending, rising "leverage" risk as financial firms held too small a cushion of capital relative to their assets, and a "common shock" when it turned out that many firms had essentially made the same bet on the housing market and mortgage-related securities.

The Republicans also deal bluntly with one of the most debated events of the crisis: the failure of Lehman Brothers. For two years, a prevalent view has been that Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, former Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, and Timothy Geithner (then head of the Fed's New York branch) should have found a way to avoid Lehman's bankruptcy.

"In hindsight, we also think they were right at the time – they did not have a legal and viable option to save Lehman," said Mr. Hennessey and his colleagues.

Although Lehman itself went bankrupt, the Republicans also review the problem of bailouts, in which policymakers "fear [financial] contagion so much that they are unwilling to allow [a firm] to go bankrupt in a sudden and disorderly fashion."

Congress has passed financial reforms, but it remains to be seen if the legislation deals adequately with that issue, known as the "too big to fail" problem.

The commission's other Republican member, Peter Wallison, offered his own dissenting analysis, emphasizing the idea that government housing policies sowed the seeds of the crisis.