'Geronimo' and Osama bin Laden: What goes into a code name?

Loading...

On May 1, President Obama and others in the White House situation room heard the words, “We’ve ID’d Geronimo,” and soon got the word that Osama bin Ladin had been killed: “Geronimo EKIA,” shorthand for “enemy killed in action.”

It is not known which branch of the armed forces or intelligence community decided to use "Geronimo" as the code name for Mr. bin Laden during the Sunday raid of his compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. But that choice has left some Native Americans unable to fully celebrate what otherwise would be welcome news.

The issue will be discussed at a Senate Indian Affairs committee hearing Thursday. The hearing on racial stereotyping of Native Americans had been scheduled prior to bin Laden’s death.

Hours after the Geronimo code name was reported, reports suggested that White House officials had revised the story, saying Geronimo was a general name for the operation, not for bin Laden himself. Historically, code names have ranged from affectionately flippant to openly disparaging, and sometimes reflect how the government organization bestowing the name views the person.

Pope John Paul II was called "Halo" by the Secret Service. The ruddy Sen. Edward Kennedy was known as "Sunburn" during his 1980 presidential bid. Todd Palin, an oil field operator and husband of vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin, was dubbed "Driller" by the Secret Service.

During the Cold War, when code names for Cubans began with “AM,” Cuban President Fidel Castro was known as "AMTHUG," and fellow revolutionary Che Guevara was known as "AMQUACK." More recently, during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the CIA code named a group of helpful Iraqi spies "DBROCKSTARS." Rafid Ahmed Alwan al-Janabi, whose lies about Iraq’s weapons program gave credence to the US invasion in 2003, was code named "Curveball."

The story of Geronimo

Bin Laden and Geronimo both evaded the US government for nearly a decade, but Native American groups say the similarities end there.

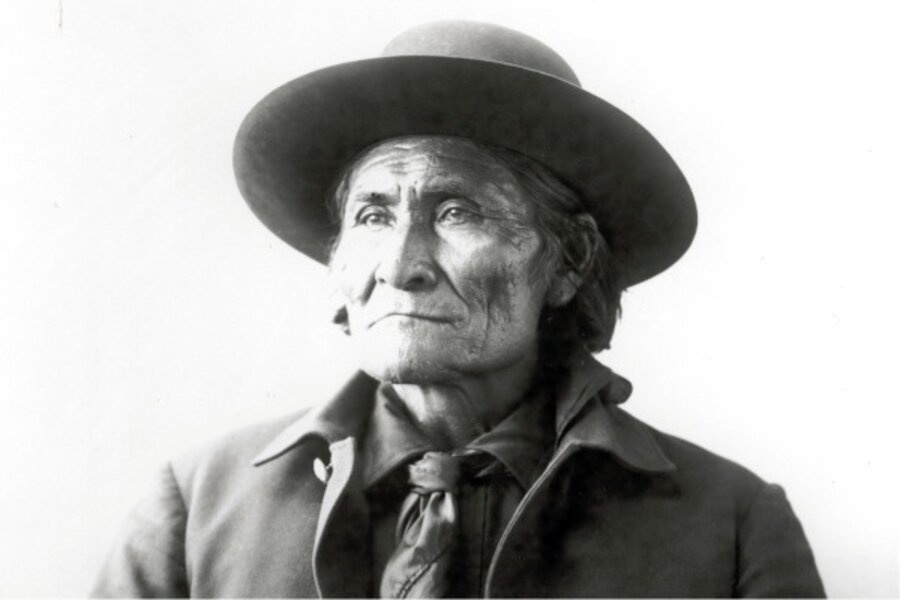

Geronimo, a Chiricahua Apache, became a hero to Native Americans in the 1800s as a symbol for anticolonialism. He battled Mexican and American troops for nearly 30 years, protesting the relocation of native peoples to reservations. He avoided capture during a decade-long manhunt that used 5,000 soldiers, as he and his followers refused to accept American sovereignty over the West. Geronimo finally surrendered in 1886, and remained a prisoner of war until his death in 1909.

"He was one of the brightest, most resolute, determined-looking men that I have ever encountered,” wrote General Nelson A. Miles, who pursued Geronimo and eventually accepted his surrender.

Native American columnists say associating Geronimo with bin Laden reaffirms the notion that Native Americans are not truly accepted in American society.

“Embedded within it is a message that an Indian warrior, a symbol of Native American survival in the face of racial annihilation, is associated with modern terrorism and the attacks on 9/11,” wrote Lise Balk King for Indian Country Today Media Network.

Native Americans in the armed forces

Today, a higher proportion of Native Americans serve in the US military than any other ethnic group. In 2007, they made up 0.7 percent of the US population but represented 2.7 percent of the armed forces.

“They let us serve their country and die for them and then they tag us with this? All the Indian Veterans are angry,” Vietnam veteran Lloyd Goings told the Native Times.

The Onondaga Nation council of chiefs released a statement blasting the government’s use of Geronimo, and saying that World War II’s famous codebreaking Windtalkers saved thousands of Allied lives, even as they were persecuted at home.

“Ironically these brave men and women were using languages that American and Canadian boarding schools were doing their best to stamp out,” said the statement.