Flash mob attacks: Rising concern over black teen involvement

| Atlanta

State police are roaming the Wisconsin State Fair in Milwaukee, looking for teenage troublemakers. Philadelphia is stepping up enforcement of a curfew for teens in the Center City business district. Chicago police have beefed up patrols along the city's "Miracle Mile" district in response to recent teenage "flash robs," some which police say were orchestrated via social media.

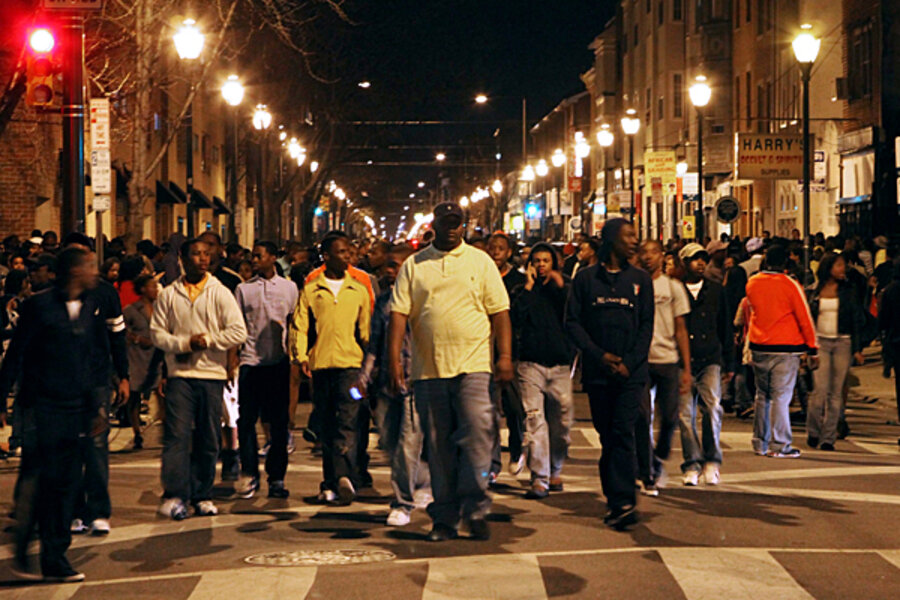

What connects the three city crackdowns are teen-perpetrated crimes that are part opportunistic, part thrill-seeking, and, some residents fear, part racially motivated: dozens of black teenagers collectively targeting, and attacking, white people they don't even know. Resentment fueled by dogged segregation, poor unemployment opportunities for young black men, and historic inequalities may all be playing into an atmosphere of racial discontent, sociologists say.

"[Mob violence] certainly doesn't seem to be a national problem, but [police are indicating] there's now reason to believe that it could potentially emerge as a problem," says Sean Varano, a criminologist at Roger Williams University, in Bristol, R.I.

On Monday, Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter said he would add street patrols and start enforcing a 9 p.m. weekend curfew for 13- to 18-year-olds for the Center City arts and shopping area. He took the step after a series of incidents over the past two years, including two in the past two weeks, in which black teens beat up on their victims, who were primarily white.

In a message Monday to the mob suspects, Mayor Nutter, Philadelphia's third black mayor, said, "You have damaged your own race."

"These are majority African-American youths and they need to be called on it," the head of Philadelphia's chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, J. Whyatt Mondesire, told the Washington Times.

Philadelphia "is taking the flash mobs seriously, particularly the troubling racial dynamic that makes whites most vulnerable to the attacks," writes Eugene Kane, a columnist for the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, who was visiting Philadelphia when the Wisconsin State Fair attack happened.

On Friday, Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker (R) ordered extra state troopers to the fair in Milwaukee after a group of witnesses reported that dozens, perhaps hundreds, of black teenagers began fighting with one another Thursday night on the midway, then began punching and kicking white people outside the fairgrounds, including pulling them out of cars and off motorcycles. Teenagers at the fair, which closes Aug. 14, now must be accompanied by adults at night.

One police officer characterized the Thursday incident as a "mob beating" in which several police officers were also hurt, but Milwaukee detectives continue to investigate the attacks and have not released a motive. Several Milwaukee news outlets, however, painted a more troubling picture: "Witness accounts claim everything from dozens to hundreds of young black people beating white people as they left the state fair Thursday night," noted WTMJ-4, the local NBC News affiliate. “It looked like they were just going after white guys, white people,” festival-goer Norb Roffers told Newsradio 620.

Some city leaders quickly noted the racial aspects of the melee at the fair.

"Sadly, what transpired near State Fair Park ... is only the most recent mob riot spawned by a culture of violence that has been brewing in Milwaukee for some time," said city Aldermen Joe Dudzik and Bob Donovan, who are both white, in a joint statement on Friday. "And let’s face it, it also has much to do with a deteriorating African-American culture in our city."

Some black city leaders said that hate crime prosecutions for the perpetrators should be on the table. "Hate crime enforcement must take place: Attacking anyone based on their ethnicity or color means a racial hate crime should be an additional" charge, said Milwaukee Common Council President Willie Hines, who is black, on Saturday.

Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett, who was severely beaten at the state fair two years ago in what was deemed a nonracial altercation, skirted a question from a reporter about whether he believed the incident had racial roots. But he said, "This is not random, this is calculated; these are young people who are trying to create havoc." Mr. Barrett also said the mob may have been organized through digital social media platforms.

If not an outright trend, organized mobs of mostly black teens who target whites are catching notice of police – and are raising uncomfortable issues in cities like Milwaukee, one of the most racially segregated in the nation.

"The black kids at the fair started by beating up each other, police said, and at closing time they turned that rage on whites outside the gates," writes Journal-Sentinel columnist Jim Stingl. "This newspaper normally avoids mentioning the race of people involved in crime, unless it's part of a description to help apprehend someone at large. But this incident, along with the looting and racially motivated beatings in Riverwest last month, has forced the issue."

In Milwaukee, stark racial segregation and a growing income gap between blacks and whites, exacerbated by the poor economy, may have contributed to the tension at the state fair on Thursday, suggests Stephen Richards, a sociologist at the University of Wisconsin, in Oshkosh.

"We have such a high unemployment rate for teenagers in Milwaukee, so you've got kids that have enough money to get into the state fair, but maybe they ran out of money to entertain themselves," says Professor Richards. "So you might have teenagers standing around and feeling dejected … and maybe seeing other young people that do have money. I think there is resentment, and this has happened historically in America: hot summers, high unemployment, poverty lead to problems."

Criminologists are quick to note that youth crime on the whole is at a 40-year low, and that the recent mobs pale in comparison to race riots like those in the '60s and early '70s and the Rodney King riot in Los Angeles in 1992.

Yet the racially charged mob attacks, to some, may serve as a warning of deeper and intensifying problems in the black community, including a growing divide between poor and middle-class blacks.

"It is not unlikely that future violence in the cities would look more like flash mobs and less like the urban riots of the 1960s," Walter Russell Mead, a humanities professor at Bard College, at Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y., wrote on Sunday. "Those riots targeted Black neighborhoods, Black owned stores and much of the property destroyed in the riots belonged to Blacks; any new trouble would likely be more effective at spreading the pain beyond the inner city."