Drought: USDA throws livestock farmers a lifeline. Will it help?

| Chicago

William Tentinger spent the morning giving shots and tending newborn piglets among 4,000 pigs on his Iowa farm. He also spent time wondering how much more the cost of feed will rise, and how many more pigs he’ll have to sell at a loss.

With the current drought, “there’s just no way we’re going to make any money on hogs in the future,” he says.

In the face of this summer’s withering weather, the US Department of Agriculture Monday gave what farmers like Tentinger saw as a modest show of support, offering to buy up $170 million worth of meat products between now and Sept. 31.

Livestock farmers have been squeezed hard this year, forced to pay dramatically higher prices for feed, which consumes much of the American corn crop. Prices for meat have risen, too, but not as fast as the cost of feed.

The USDA says the buy-up will help support the price of meat even as farmers who raise hogs, chicken, sheep, and even catfish, cut back their flocks, herds, and stocks to save money on feed. The meat will go to government food programs, such as school lunches and food banks.

The program excludes farmers who raise beef cattle. Although they, too, have been selling off animals to reduce costs, the USDA says the selling off will likely end soon.

Most of the money, $100 million, will go to the nation’s hog farmers to buy up pork, though the money is unlikely to have a large effect. Annual pork sales, according to the USDA, are $97 billion.

“We’re very appreciative of it,” says Mr. Tentinger, who farms in Le Mars, Iowa, near the Nebraska border, and is president of the Iowa Pork Producers Association.

The money could help buoy pork prices somewhat: “It’s a little relief in the short run,” he says.

Other industries had much the same reaction. Up to $50 million will go to helping the poultry industry, which John Starkey, president of the US Poultry & Egg Association, says will help struggling producers.

But US poultry farmers produce an average of 50.4 billion pounds of chicken meat annually, which means that the $50 million was “not a lot,” a spokesman for the association says.

Livestock farmers are likely to continue struggling as long as feed costs remain high. Tentinger says the cost of feed for his hogs has risen 30 to 40 percent since the drought began in June.

The price of catfish feed, says Roger Barlow, executive vice president of Catfish Farmers of America, has risen as much as 65 percent. Catfish feed includes corn, soybeans, and other supplements.

Experts in the meat business say the difficult times for livestock farmers are likely to force some farmers out of business, especially smaller farmers, and exacerbate the consolidation that has reduced the number of livestock farmers in recent decades.

Ron Birkenholz, a spokesman for the Iowa Pork Producers Association, says the drought has been especially hard on newer farmers who often get into farming by raising livestock because it requires little investment in land.

“They don’t have anything else to fall back on,” he says.

The USDA last week said its estimate for the US corn crop this year is the lowest since 1995-1996, when far fewer acres were planted: 123 bushels per acre. Traders on Chicago’s commodities exchange, meanwhile, have sent prices for corn and soybean crops to all-time highs.

Like livestock farmers across the US, Tentinger says he’s looked for strategies to weather the tough times. He has sold off some of his animals, culling the less productive ones. He has looked for alternative feeds, like wheat, but their cost is high, too. But unlike cattle, hogs can’t eat grass or the stalks of drought-ravaged corn. They need grain.

“There’s not much out there,” he says.

Mainly he’s decided to cut his losses by selling his hogs sooner: three weeks before they reach full weight. He says he’ll save $12 per animal by spending less on feed.

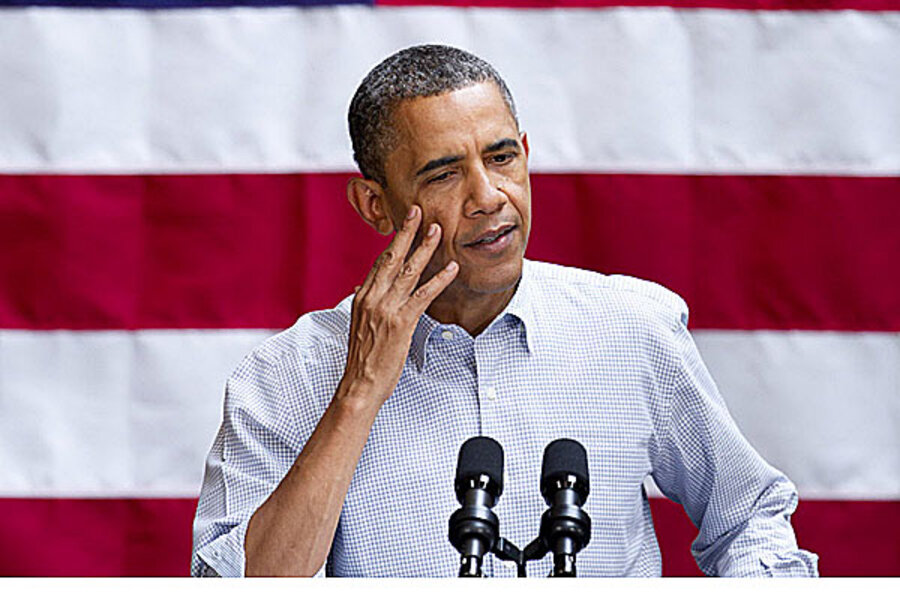

The USDA program is one of several measures the Obama administration has taken to help out farmers suffering because of the drought. Within the past month the administration has allowed farmers to cut hay on conservation lands to provide forage for their animals.

But the administration has stopped short of granting livestock farmers their key request: a suspension of the federal mandate requiring petroleum refiners to blend about 9 percent of ethanol into their gasoline. Ethanol consumes about 40 percent of the American corn crop, and livestock farmers and their representatives argue that lifting the mandate would lower prices for corn and the feeds made from corn.

Even the UN Food and Agriculture Organization has called for lifting the mandate.

Agricultural economists, however, are skeptical that it would have the desired effect. And corn producers strongly support the mandate and wield considerable political clout in swing states like Iowa.

Catfish farmers have been especially struggling. Competition from imports has already driven many farmers out of business.

Raising catfish right now, Barlow says, “is not even close to break even.”