For Latinos, Anaheim gang sweep rubs riots' wounds. Should police have waited?

Loading...

| Anaheim, Calif.

For the police in Anaheim, where the rates for murder and crime in general have soared over the past year, the gang sweep was an operation that could not wait.

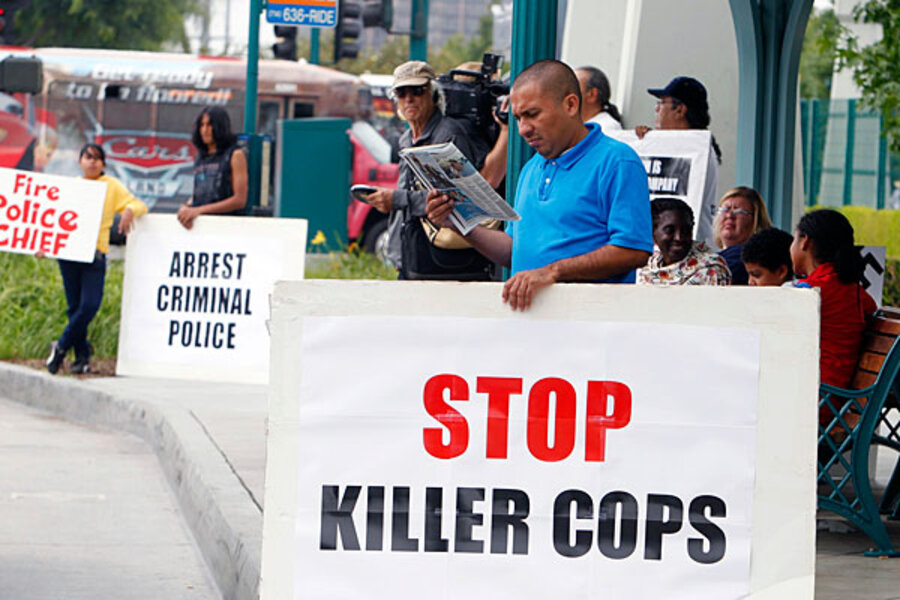

But for many residents of the mostly Latino neighborhoods where the sweep took place, the police action last Friday, dubbed “Operation Halo,” was just a power play following a riot-filled July and early August.

Whether the operation achieves the stated goal of reducing crime in California’s 10th-largest city remains to be seen, but for the time being, the residents’ bitter reaction points to a deep mistrust of city officials that is lingering weeks after the fatal police shootings that sparked the riots.

The police sweep Friday, a massive sting operation targeting a group known as the Eastside Anaheim gang, resulted in the arrests of 33 purported gang members. In addition to the arrests, the department’s Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms seized 40 guns and nearly 12 pounds of crystal methamphetamine.

According to police, crime in the affected neighborhoods was so bad that the sweep couldn’t wait, even though communities here are still reeling from the violent riots sparked by a series of officer-involved shootings in recent weeks.

"We decided we couldn't put this off any longer," Anaheim Police Chief John Welter said in a Friday press conference detailing the operation. "We can't wait until another person gets shot."

But while the department acknowledged the potentially problematic timing of the crackdown (saying it even considered a delay), residents see it as retaliation.

“I think they’re doing a payback to the community,” insists Yecenia Rojas, who lives in the Anna Drive neighborhood of west Anaheim next door to the small apartment building where an officer shot and killed Manuel Diaz, a local man who police say had gang ties. “They’re trying to tell us that they’re the ones that control Anaheim. They want us to be afraid.”

“We’ve been asking police to stay out of our neighborhoods for now, because this isn’t a good time,” says Martin Lopez, a community organizer and recording secretary for Unite Here! Local 11, a union representing hotel and restaurant workers. “People feel the police are coming in and making fun of them, that this is a retaliation for all of the press, all of the attention that is being called out on Anaheim.

“These police units, they know who gang members are,” he adds. “They know precisely where they live, they can wait and arrest these guys any time. No. They come in and tear down your doors, destroy people’s homes. So not only are they not helping, but they come in and make them feel worse.”

Ms. Rojas, a leader and self-described “big mouth” of the tightly knit Anna Drive community, has known most of the men arrested on the street for years – some from the time they were small children.

“Arturo, oh my God. He’s a nice guy,” she says, fingering a typed sheet of paper detailing the names and charges of those arrested from Anna Drive. “If anyone needs their car fixed, he’s the one. He works at the Wendy’s. He saw everything when the cops killed Manuel. So why did they take him? He might be guilty of having a ticket or something, driving without a license. But he isn’t doing what the police say he did.”

A soaring crime rate and a feeling of disenfranchisement among Anaheim’s poor have boiled over into a chaotic summer for Anaheim. More than 54 percent of the city’s 336, 265 residents are Latino, and a good chunk live in the western “flatlands” neighborhoods, apart from the more affluent, white “Anaheim Hills” in the east.

Westside community leaders have been working for years to change the city’s electoral process for more equal representation, fighting, along with the ACLU, for a districted election system wherein local officials would have to live in the neighborhoods they represent.

Of the five City Council members that comprise Anaheim’s city government leadership, including Mayor Tom Tait, only one lives outside of Anaheim Hills.

As a result, Lopez says, the Westside gets left behind. “Our young kids are growing up, there are no jobs, no programs for them – those things are offered in other areas that don’t need them. City Council has been ignoring that cry for help.”

Over the past year, Anaheim’s crime rate has jumped 10 percent, and the murder rate has nearly doubled. Gang violence has definitely become a concern, Lopez says, adding that until recently, residents were trying to work with the police to address the problem. “It helps when there is a police presence in a more positive way,” he says, outlining efforts including meetings and community walks involving police in neighborhoods with gang activity.

But in recent weeks locals have become much more fearful of police than they are of gangs. “We thought things were going well, until, boom [the shootings and riots] happened and I feel like everything went down the drain. When people see police in military fatigues and riot gear, pointing assault weapons at you, what do they expect?” he says. “People get really nervous, thinking, am I going to get shot today?”

“If criminals realize residents are afraid of us, they exploit that,” Police Chief Welter said Friday.

The department says the crackdown was successful in making the troubled neighborhoods safer, and that public reaction has been generally positive.

“We had residents coming up to our officers offering handshakes and thanks for our efforts,” wrote Anaheim Police Department spokesman Sgt. Bob Dunn via e-mail. “This operation has taken many of the gang’s leadership off the streets. Our hope is that we can help the neighborhood with services and skills that will help them take ownership of their neighborhood. This will allow us to work with them on crime prevention.”

But Rojas, who was hit was rubber bullets the night the July 25th riots broke out outside City Hall, thinks the police just want to portray her community and others like it in the worst possible light. “This is not for the Anna Drive that the media is putting on TV,” she says. “We want peace, we have dignity, and we deserve to be treated with respect.”

Even so, Rojas says she and her husband are looking to move away from the street she has lived on since age 7, for the sake of their six children. “It’s gotten too dangerous. We’re looking to see if we can get a house. I have to think about the kids.”