Trump wants a 'top of the pack' nuclear program: does that actually signal a shift?

Loading...

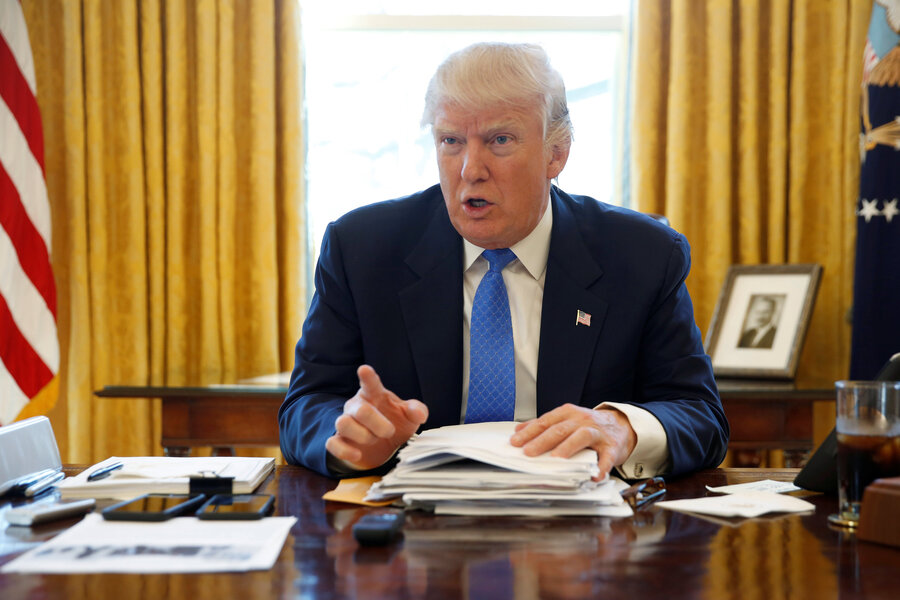

President Trump doubled down on his earlier tough talk on nuclear-weapons policy in an interview on Thursday, standing by a January tweet calling for the strengthening and expansion of the nation’s nuclear capacity.

"We've fallen behind on nuclear weapon capacity," he told Reuters, according to a transcript. "And I am the first one that would like to see … nobody have nukes, but we’re never going to fall behind any country even if it’s a friendly country, we’re never going to fall behind on nuclear power."

More than 90 percent of the world's nuclear warheads belong to Russia and the United States, according to the Arms Control Association, with Russia recently surpassing the number of those held by the US – though most arms-control experts say that the US probably has greater capability. The total US holdings of 6,970 warheads reported by USA Today in December is well down from the 1967 peak of 31,255.

Mr. Trump offered little clarification this week of how his stewardship of nuclear weapons would break with that of previous presidents.

“It’s ambiguous,” says Vipin Narang, a political scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Mass., who studies states’ use of nuclear weapons.

That vagueness in signaling, he tells The Christian Science Monitor in a phone interview, and tends to be a recipe for escalation, as rivals and allies alike often assume the worst-case scenario.

“These words matter. In nuclear jargon, there is a very calibrated language for signaling uses,” he says.

But the president’s remarks may also turn a spotlight onto the unresolved questions of the Obama administration’s nuclear modernization project – one likely to absorb much of the new president’s enthusiasm for arms escalation.

Nearly the entirety of US nuclear systems, from warheads to the missiles, submarines or bombers that deliver them, date back to the eras of former Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan.

“They’re all at different points, but all need to be replaced more or less at the same time,” says Jeffrey Lewis, an arms-control expert at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies in Monterey, Calif. “So that leads to the question of, how much is that going to cost, and can we replace them fast enough?”

Before leaving office, former President Barack Obama authorized $1 trillion for the project over 30 years, in a move that was widely panned by weapons experts as unserious, and a way of passing the decision off to his successor.

“In short, the current nuclear spending plans are a fantasy,” wrote Kingston Rief of the Arms Control Association last February.

Only with big, long-term increases to military spending over the next decade, or shifts in funding away from other military and national-security modernization programs, could the plans be achieved, he argued.

“The most likely outcome is that the current plans will collapse under their own weight and force reductions in U.S. nuclear forces,” he added.

“Most of us don’t believe that the modernization plan is executable,” Dr. Lewis tells the Monitor. “And the Obama people were very clear” that they were glad that the problem would not be theirs to solve, he adds.

In the interview with Reuters, Trump also criticized New START, the arms-control treaty with Russia that led to funding for the modernization-project, as “just another bad deal” and “one-sided.” But it may well be that any push for build-up would come within the parameters of the treaty.

Rebeccah Heinrichs, a nuclear-deterrence specialist and fellow at the Hudson Institute, applauded Trump’s vow to expand and strengthen the nuclear arsenal in a January essay, arguing that Russian violations of the treaty meant that the US “must do exactly what Mr. Trump said it ought to do.”

“This does not mean the United States must expand its numbers beyond the treaty limits; rather, it should expand in number within the boundaries of the treaty, because although the Russians are above New START Treaty limits, the United States is below them,” she wrote.

Dr. Narang, the MIT political scientist, says there has been “a lot of continuity” in how previous presidents ended up stewarding nuclear force because of political and bureaucratic resistance.

For now, there are a few clear red lines.

“It becomes different if [Trump] is talking about building new warheads. And testing is a red line. If we start, that opens the door for China, India, North Korea” and others, he says. “And we lose.”