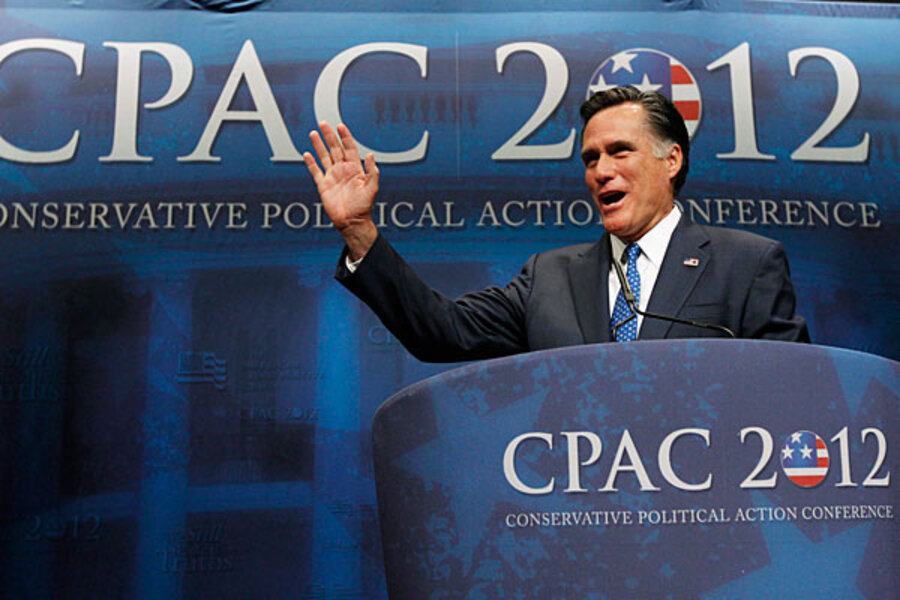

When Mr. Romney boasted in February that he had been a “severely conservative Republican governor” of “deep blue” Massachusetts, attendees at the Conservative Political Action Conference scratched their heads. There was Romney, trying again to convince the GOP’s conservative base that he was one of them, when his relatively moderate record as a Massachusetts politician says otherwise.

He used to support abortion rights, gay rights, and gun control, but now he opposes them. He used to support comprehensive immigration reform, including a path to citizenship for those in the US illegally, but now he doesn’t. He once said his reform of health care in Massachusetts could serve as a model for the nation, but now he’s eager to undo President Obama’s Affordable Care Act, if the Supreme Court doesn’t get there first.

Romney shifted to the right to run for president in 2008, and he has stayed there since. But he still calibrates himself at times. At a Republican debate in January, he softened his opposition to the DREAM Act – legislation that provides a path to citizenship for some young undocumented immigrants. When Newt Gingrich said he would allow legal status for those who join the military, Romney said he would, too.

In a recent focus group of mostly conservative voters in Tampa, Fla., the most common concern raised about Romney is that he’s been inconsistent on the issues. “Make a stand whether people like it or not,” said one participant, a middle-aged paralegal named Julie, according to NBC News.

A New York Times/CBS News poll issued April 18 found that only 27 percent of Americans think Romney “says what he believes” versus 62 percent who think he “says what people want to hear.” Mr. Obama scored 46 percent on “says what he believes” and 51 percent on “says what people want to hear.”