NATO summit: Why US, allies don't just call it quits in Afghanistan

Loading...

| Washington

Why can't the United States just make a clean break in Afghanistan, the way it did in Iraq?

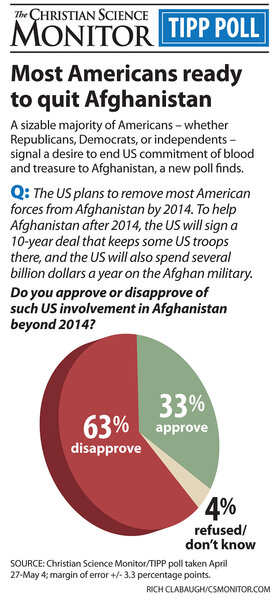

That question may occur to many Americans upon learning that NATO countries are poised this month to lay out their post-2014 commitment to Afghanistan. After all, more than 6 in 10 disapprove of a US-Afghanistan pact to foot much of the bill for Afghan forces and to keep American troops there after 2014, according to a recent Christian Science Monitor/TIPP poll.

The answer to the question can be distilled to three parts: Al Qaeda, oil, and Pakistan.

The US and NATO have been on the ground in Afghanistan for nearly 11 years, trying to build up Afghan security forces, among other things. But those forces still are not ready to shoulder security duties without outside help.

Thus, the primary goal that the US set for itself once it routed the Taliban from power remains to ensure, as President Obama has said, "that Afghanistan does not again become a safe haven for terrorists."

With the Al Qaeda leadership weakened but alive across the border in Pakistan, the US wants to maintain a robust counterterrorist capability in Afghanistan.

Another factor is oil – or rather, in Afghanistan's case, a lack of it. In Iraq, the US could exit abruptly because the central government had the revenues, thanks to plentiful oil deposits, to provide basic services and to field adequate Army and police forces to maintain security. But Afghanistan has no such revenues, although it is working to open up development of mineral deposits that may ultimately provide them.

That means the NATO-trained military and national police can't keep operating unless the US and other countries chip in for years to come.

Then there's Pakistan. As Stephen Biddle of the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington says, "Essentially, the answer to the 'why not just leave' question is what it's always been: It's the unstable nuclear Pakistan with Islamic militants gaining strength that's right next door."

An American presence in Afghanistan reassures the Pakistani government that the US is not going to leave behind a void (one that might be filled by archenemy India?) that Pakistan has to worry about and plan for.

But also, many say, a US presence reduces the likelihood that Afghanistan will collapse into civil war, which could spill across the Pakistan border in the form of heightened instability.

That, says Dr. Biddle, is "a pretty scary prospect."

To these three reasons, some experts add another: the "paid too much to throw it all away" argument.

"In Iraq, we'd got to the point where if we left we were pretty sure all would not be lost, but nobody can say that about Afghanistan," says David Pollock of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

"It's like when you've made all the sacrifices to make 99 payments on your car and you have one more to go," he adds. "Even if it's a rough moment for you and making that last payment is the last thing you want to do, you're going to do it, because if you do you're going to keep the car."