Social Security: Is reform needed now or not?

A proposal by President Obama, in fiscal talks with Congress, has put Social Security back in the news.

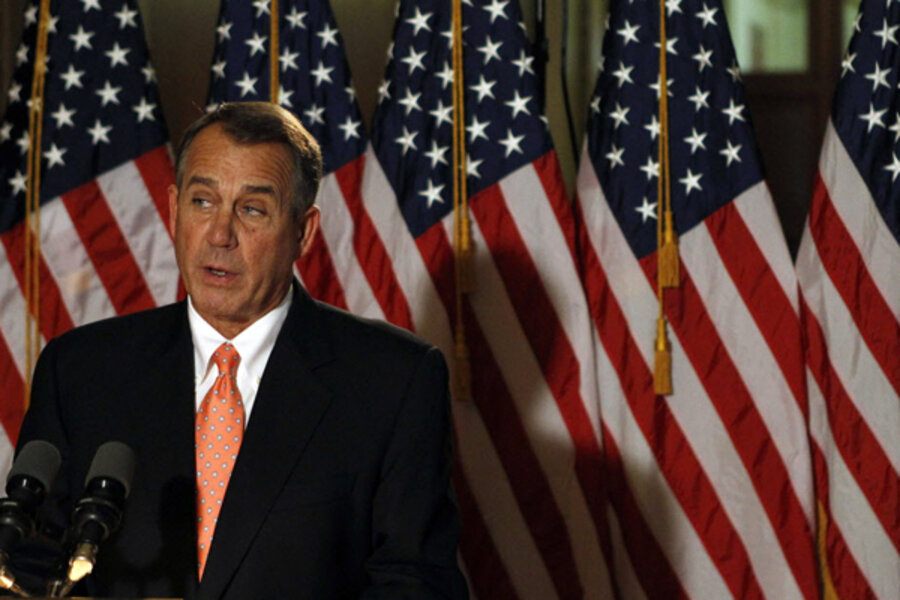

The president's latest deficit-reduction offer to House Speaker John Boehner (R), summarized in news reports early this week, includes the idea of changing the way inflation is calculated when making annual adjustments to Social Security benefits.

The move is controversial, and it brings to the forefront a basic question: Does Social Security need reforms right now, or not?

Some budget experts praised Mr. Obama for agreeing with Republicans on the idea of shifting to what's called a "chained" version of the consumer price index (CPI) to calculate cost-of-living adjustments in retiree benefits.

They argue that the chained CPI is a more accurate guide to the cost of living. Basically, this gauge would take into account not only changes in prices for various goods, but also the way consumers respond to prices by adjusting the mix of goods and services they buy. And supporters say that, because the result will be modestly smaller cost-of-living increases, the move will help to put Social Security's finances on track.

Opponents of the move call it a sneaky way to cut benefits in a program on which millions of Americans rely. Some of these critics reject the idea that Social Security requires urgent attention. In many cases, they conclude that the widely popular entitlement needn't be part of the "fiscal cliff" talks at all.

America's large federal deficits in the past few years, after all, stem from a range of other forces, including the effects of recession, the Bush tax cuts, and high military spending over the past decade.

So which is it – does Social Security need to be addressed now or not?

The short answer is that the program is not a money-loser for the federal government right now, but does face a funding shortfall in the fairly near future. The program's trustees say the best time to act is now, not later. (Details can be seen in bullet points below.)

"It will become increasingly difficult to avoid adverse effects on current beneficiaries, those close to retirement, and low-income beneficiaries ... if legislative changes are delayed much further," the trustees said in their latest annual report.

While this assessment doesn't answer the question of whether to shift to the chained CPI, the trustees' view that action is needed, and that Social Security should be shored up sooner rather than later, is shared by many budget experts across partisan lines.

"While Social Security’s shortfall is manageable, it is also real," Alicia Munnell, director of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, wrote in an analysis earlier this year. "The long-run deficit can be eliminated only by putting more money into the system or by cutting benefits. There is no silver bullet."

A summary of Social Security's current status, according to the 2012 trustees' report:

• The trust fund to support retirees (Old Age and Survivors Insurance) is estimated to be exhausted by 2035, a year sooner than was estimated in 2011. Absent any legislative changes, beneficiaries after that date would face a reduction in benefits, because payroll-tax income would not cover all currently promised benefits.

• The program's other main trust fund, for Disability Insurance, will be exhausted by 2016. Again, if unaddressed, that would prompt a benefit cut for disabled workers.

• The two trust funds are legally separate. But the trustees said that if the two parts were merged, Social Security benefits could be paid in full through 2033. Then benefits would have to be cut by 25 percent.

• Combined, the two parts of Social Security face a projected 75-year deficit equal to 2.67 percent of the nation's taxable payroll, up from a projection of 2.22 percent as of 2011. "This is the largest actuarial deficit reported since prior to the 1983 Social Security amendments," the trustees said, and the largest single-year deterioration since 1994.

Put another way, the projected imbalance in Social Security is equal to about 1 percent of the nation's projected economic output over the next 75 years. So, as Ms. Munnell stated, the problem is manageable but not insignificant.

• Since 2010, Social Security benefit payments have been exceeding the program's income from the payroll tax. For old-age benefits, interest earned within the trust fund is covering the difference. On the disability side, the program is using both interest income and principal from its trust fund.

Although its problems are real, the existence of the trust funds mean that Social Security is not technically a contributor to current budget deficits. But Congress often portrays the budget picture on a "unified" basis, which incorporates the trust funds into the larger budget picture. In that framework, the trustees projected Social Security to have a $53 billion deficit this year. A temporary payroll-tax break, which is expiring at the end of this year, had no impact on that number.

For reference, American workers and employers each pay 6.2 percent of payroll wages toward Social Security (a combined payroll tax of 12.4 percent). Medicare has an additional payroll tax on employers and workers, bringing the grand total to 15.3 percent.

Payroll taxes have risen numerous times over the years. That could happen again, eventually, if other fixes aren't found. In polls, Americans have shown little receptivity to broad cuts in benefits.

In the end, a mix of steps may be the answer, including things like greater means-testing (to reduce benefits for the wealthy), use of the chained CPI to gauge inflation, slowly increasing the official retirement age, and raising the cap for income subject to the payroll tax.

Some liberals and conservatives, such as bipartisan members of the Simpson-Bowles fiscal commission created by Obama, have pointed the way toward potential compromise.

"A mix of tax increases and modest benefit reductions – carefully crafted to shield the neediest recipients and give ample notice to all participants – could put the program on a sound financial footing indefinitely," the liberal Center for Budget and Policy Priorities concluded in a recent analysis.