Jobs report finds little overall progress. Why is recovery so slow?

The US unemployment rate held steady at 7.8 percent in December, with the good news being that the job market didn't stumble because of high-stakes brinkmanship in Washington over taxes.

For now, the job market has dodged the "fiscal cliff," but employment growth is also notably slower than in past recoveries from recession.

The economy added 155,000 jobs in December, the Labor Department said Friday as it reported the results of its monthly survey of employers. A separate survey of US households found the unemployment rate unchanged, as tepid job growth was more than matched by the entry of new people into the labor force to look for work. The jobless rate for November, which had been initially reported as 7.7 percent, was revised up to 7.8 percent.

"Some of the uncertainties in the economy have been removed with the fiscal cliff agreement [on tax rates for 2013], but Congress failed to address the debt and deficit issues which will still be a drag on the economy," said Chad Moutray, chief economist at the National Association of Manufacturers, in a written analysis of the labor report.

Manufacturing was one of the bright spots in the monthly numbers, showing a gain of 25,000 hires on employer payrolls.

But overall, the key phrases in the Labor Department's description of the job market were "essentially unchanged" and "little changed." The stock market reacted in kind, with the Standard & Poor's 500 index essentially flat Friday morning after the news.

Why has the jobs recovery since the recession, which officially ended in 2009, been so slow?

Before looking at some answers, here's the evidence on how the current job market compares with that in past recoveries.

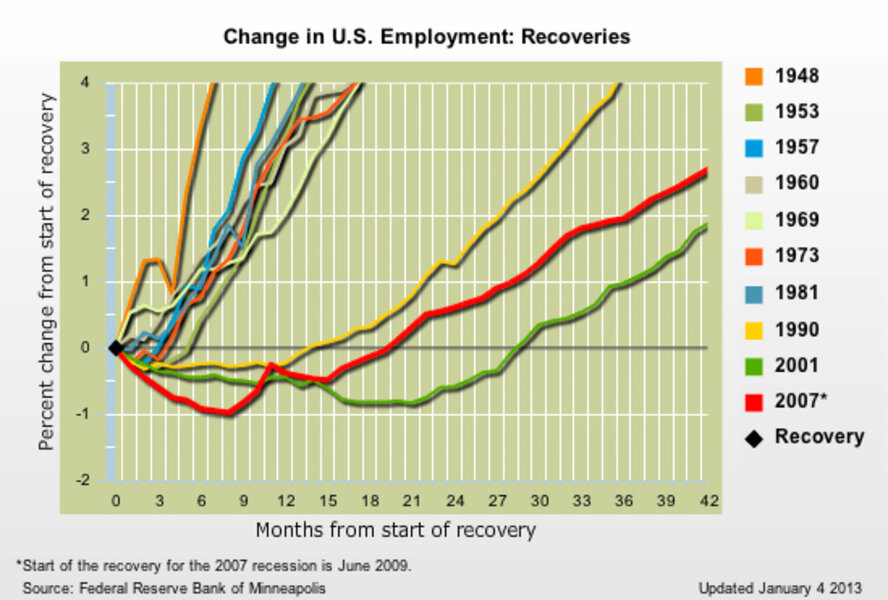

The current pace of recovery is weaker than in the other recoveries since 1948, with the possible exception of the period after the economic slump of 2001.

Prior to 1990, economic recoveries tended to show a fairly quick rebound in jobs, with total US employment rising 4 percent or more within about 15 months. The past couple of decades have been a period of "jobless recoveries," where the progress tends to be slower. The graphic attached to this article (see box near the upper-left part of the story) tells the story visually.

A quick note about the chart: The version shown here omits the 1980 recession for more visual simplicity, since the aftermath includes another recession and recovery. You can visit the original interactive version of the chart at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

After the 1990 recession, it took three years for the economy to create 4 percent more jobs. After the recessions that began in 2001 and 2007, it's been even more challenging.

Today, some 42 months after the official end of the recession, employment growth is below 3 percent. And after the 2001 recession, job gains hadn't even reached 2 percent after 42 months.

So, by that gauge, this is the worst performance other than the period after 2001. And in some ways, the current recovery lags behind even that post-2001 period. Today, total US employment is still about 3 percent below the peak it hit as the recession began. By this time after the 2001 recession, jobs lagged behind their earlier peak by about half that much.

Now for the why.

The biggest and most obvious answer has to do with debt. Recoveries after a financial crisis, when a nation is struggling with high debt burdens, tend to be protracted, many economists say. That shows up in various areas of the economy. Debt-strapped consumers boost their spending at a slower pace. Home construction doesn't rebound the way it normally would, thanks to the aftereffects of the housing bust. Federal and state governments are looking at lean tax revenues and aren't hiring.

Even foreign trade is affected, since the debt crisis is to some extent global. And all of the above affects the confidence of business to make new investments.

The housing market has begun to recover, and US consumers have been making progress in lightening the burden of debt. Many mortgage borrowers have already been foreclosed upon. Other families have avoided taking on new debts. But the process of "deleveraging" is still under way.

But a debt overhang may not be the whole story. After all, the other two recoveries since 1990 have also been characterized by disappointingly slow job growth.

Economists are exploring possible explanations, including:

• The long-term trend of eliminating middle-wage, middle-skill jobs through automation. This is a gradual process, but its effects may show up prominently in the wake of recessions.

• Decline in US competitiveness. Job growth would be stronger if the nation were better maintaining the strength of US manufacturers against global rivals, argue some analysts including the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation in Washington.

• A downshift in demand for jobs. The idea here is that job growth is partly a function of how many people want to work, and in the United States, the "participation rate" in the labor force has been falling since about 2001. A key question is how much of this is due to discouragement, as people who fail to find jobs stop looking, and how much is caused by other factors.

With the aging of baby boomers, a large chunk of adults is migrating above age 60 and becoming less attached to the job market, some economists note. Meanwhile, some younger groups such as teens and middle-aged men also show long-term declines in labor-force participation.

At the same time, many economists think the participation rate would climb from its current lows if the climate for jobs and wages improved.

About 1 million people are currently not in the labor force because they're "discouraged," according to Labor Department surveys. By comparison, some 12.2 million are officially counted as unemployed because they lack jobs and are actively looking.