Obama's icy relationship with Congress: Can it ever thaw?

Loading...

| Washington

Relations between the White House and Congress reached a low in February when House Speaker John Boehner (R) of Ohio said it would be tough for the House to move on immigration reform this year. He cited a lack of trust in President Obama to implement a new immigration law, saying he's not enforcing current ones.

Ever since Republicans took control of the House in 2010, tension and gridlock have defined dealings between the two ends of Pennsylvania Avenue. Indeed, 2013 went down as the least productive year for Congress since World War II, and it included an impasse between Mr. Obama and lawmakers that partially shut down the federal government for 16 days in the fall.

White House-Congress relations could get even more polarized if, in this fall's midterm elections, the GOP takes the Senate, where it needs a net gain of only six seats. Yet big issues, in addition to immigration, remain unresolved: weak job growth, America's expensive entitlement programs that drive up the national debt, and Iran's nuclear program, to name a few.

With three years to go in this presidency, can the relationship between Obama and Congress be saved in hopes of getting some business done? Or perhaps more realistically, can the relationship at least be improved?

It's easily forgotten, but "governing is hard work," says Leon Panetta, whose résumé includes Democratic congressman from California and former Defense secretary for Obama. "There's almost a sense now that if you run into any obstacles or you run into any serious differences, people almost give up and resort to blaming the other side."

Pinpointing the genesis of today's White House-Congress feud is like trying to unravel the rivalry between the Hatfields and McCoys. The most obvious cause is 2010, when the tea party movement poured enough Republicans into the House to flush Democrats from power and Rep. Nancy Pelosi (D) of California from the speaker's chair. Ideological rigidity stiffened.

But former Sen. Olympia Snowe (R) of Maine points to the very start of the Obama administration, when the president and Democrats in Congress passed expensive and expansive legislation along party lines. That fueled "big government" concerns among Republicans and ignited the burner under the teakettle.

Less than a month after Obama took office in 2009, the $787 billion stimulus bill passed with only three Republican votes (including the moderate Senator Snowe's). In 2010, the mammoth Affordable Care Act passed with no GOP support. Wall Street reform went through later that year.

In her book "Fighting for Common Ground," Snowe recounts the president's many attempts to reach out to her during the health-care debate – at least eight meetings with him and more than a dozen phone calls.

He made one last attempt shortly before Christmas in 2009, when they met at the White House during a snowstorm, Snowe recalls. With a fire roaring in the fireplace, Obama urged her to support the final vote on the legislation. She regretfully declined, explaining that despite all their exchanges and her meetings with Senate Democrats, there had been no headway on any of the issues she had discussed – such as her objection to the way penalties would be assessed for failure to adhere to the so-called individual mandate. It was "all windup and no pitch," she writes.

"If strong overture to the leadership and members of the minority party on Capitol Hill had been made by President Obama at the outset of his term, perhaps they could have survived other encumbrances from the respective caucuses," Snowe writes. "However, once the president deferred to Speaker Pelosi on the stimulus legislation and then turned his focus to such a massive government spending program as health care, it was unlikely he could have built a rapport with many Republicans."

For their part, political scientists tracing the origins of the White House-Congress feud look back even further – to the "Republican Revolution" of 1994 that made Newt Gingrich speaker and gave the GOP control of both the House and Senate for the first time in 40 years. It launched today's era of polarization, playing out in President Clinton's impeachment and under President George W. Bush, says Stephen Wayne, an expert on the American presidency at Georgetown University in Washington.

The polarization continues to drive moderates such as Snowe from Congress, and it feeds itself as each side responds to what it sees as the latest indignity lobbed from the other side, says James Thurber, a congressional expert at American University in Washington.

Such dynamics exist in the immigration debate. Mr. Thurber characterizes GOP comments about an untrustworthy and lawless Obama as "quite offensive" messaging, given the lengthy history of presidents using their executive power.

Specifically, Republicans criticize the president for independently deciding, rather than working with Congress, to defer deportations for children of illegal immigrants. They say he has inflated the number of removals at the border by changing the counting method, and they criticize a steep drop in deportations from the interior of the country.

GOP lawmakers also point to a host of other executive actions that they say are excessive: controlling greenhouse gases through regulation, not enforcing federal laws against marijuana and gay marriage, and, of course, delaying or revising the implementation of parts of "Obamacare," not to mention the disastrous rollout of HealthCare.gov.

Lack of trust "is an overriding issue that covers far more than immigration," says Rep. Lamar Smith (R) of Texas. Obama may not have signed as many executive orders as previous presidents, he says, but their scope is breathtaking.

On immigration, the White House has responded that the "trust" accusation doesn't stand up to scrutiny. It's merely cover for the speaker's inability to control his divided caucus on this issue, Democrats say.

More broadly, Obama has said he's being forced to act on his own because he can't get cooperation from Congress.

"I'm eager to work with all of you," he told members of Congress in his Jan. 28 State of the Union speech. "But America does not stand still, and neither will I. So wherever and whenever I can take steps without legislation to expand opportunity for more American families, that's what I'm going to do."

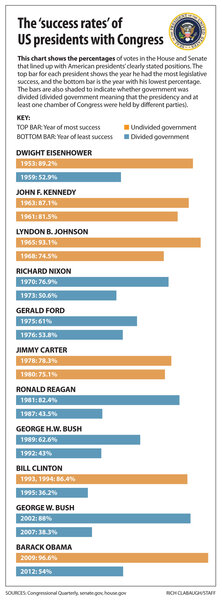

Then again, this president is hardly the first one to face a brick wall on the Hill. Obama's legislative scorecard with Congress – what's called the "presidential success rate" – is not as bad as one might think. Last year, 56.3 percent of the bills approved in the House and Senate were ones that Obama agreed with, according to Congressional Quarterly. Most presidents going back to Dwight Eisenhower have, at some point during their time in the Oval Office, batted in that range or even lower.

Even in Obama's worst legislative year so far – 2012, when his presidential success rate was 54 percent – he outperformed Richard Nixon's lowest score from 1973 (50.6 percent), when the Watergate hearings were in full swing on the Hill. Obama also scored higher than Mr. Clinton's nadir in 1995 (36.2 percent), the first year of the Republican takeover of Congress, and he surpassed the score of his Republican predecessor, Mr. Bush, in 2007 (38.3 percent), after a war-weary public returned control of Congress to Democrats.

It's important to remember that the slope from Capitol Hill to the White House is not supposed to be some downhill ski course where the president zooms toward victory after dropping off his latest idea at the starting gate of Congress. The Founding Fathers built lots of moguls to slow things down and even stop them. Those include two equal branches of Congress – not always held by the same party or the president's party; varying election schedules – two years for the House, six years for the Senate, four years for the president; different constituencies – from districts, to states, to a nation; and other checks and balances, such as the presidential veto.

What's notable about the Obama-Congress relationship is how steeply it declined. In 2009, the newly elected president of hope and change had the highest presidential success rate with Congress in the history of the modern presidency – 96.6 percent. "The drop from 96.6 to the 50s is dramatic," Thurber says.

Clinton, however, fell even further after the Republican sweep in the 1994 midterms – and he made a remarkable recovery by finding common ground with Speaker Gingrich. Is there something that Obama can learn from the "comeback kid"?

Mr. Panetta, who also served as Clinton's chief of staff, thinks so. He recalls a conversation when Gingrich first became speaker.

"The president said, 'You know, I think I could cut a deal with this guy.' I warned him Gingrich had just won with a revolution and that it was going to be hard to do. But Bill Clinton never, never lost that confidence that somehow he could find a way to get it done."

Clinton may be praised for his personal skills – his charisma, his ability to remember names, his love of the campaign rope line – but Panetta says that Clinton's post-Gingrich recovery had more to do with the fact that he never gave up trying to make deals on the Hill. Panetta suggests that both Obama and Boehner "put everything on the table" and allow a give-and-take that will lead to getting things done.

Some say Obama has basically given up, a view that Panetta shares. Professor Wayne of Georgetown posits that Obama uses GOP pushback and antipathy toward his policies, as well as his lack of personal relations on the Hill, "as an excuse not to get his hands dirty." Even some in his own party find him aloof and arrogant.

Obama wants to be more of a visionary president, Wayne explains, and assumes that everything he is in favor of will automatically be opposed. Maybe that's true, Wayne continues, "but he has not really tried."

Democrats emphatically disagree with that. In 2011, in the midst of the argument over raising the debt ceiling, Obama worked with Boehner on a long-term deal to address the debt – but had the rug pulled out from under him when Boehner wasn't able to deliver. Last year, he submitted a budget with a definite "ouch" factor for the progressive wing of his party – changing the way Social Security cost-of-living adjustments are calculated, for instance. It was declared dead on arrival by the Republicans. (And Obama's 2015 budget doesn't include this measure.)

It wasn't easy for Clinton, either, when the GOP took over the House. The first few months of Gingrich's being in charge were "horrible" for the White House, says Patrick Griffin, who was Clinton's congressional liaison. Democrats attacked the president for losing control of Congress.

But then the White House got its opening: a Republican budget that proposed to cut Medicare, Medicaid, the environment, and education. "We went for the jugular" on all those cuts, Mr. Griffin says, helped along by Gingrich gaffes.

The next election also meant Republicans needed to put some successes on the board. Clinton distanced himself from leftist Democrats to meet Gingrich on a balanced budget, welfare reform, and smaller issues.

While Gingrich faced restless troops who didn't trust him to deal alone with Clinton, the GOP division was not nearly as stark as it is with the tea party and Boehner.

Today, Republican distrust of Obama is not the heart of the issue, Griffin contends.

"If these guys wanted to do business, they would find a way to do business," he says. Congress is headed for midterm elections, and the president is facing lame-duck years. The prospects for big deals are slim. A president usually turns to smaller items and foreign policy – his phone and pen, as Obama puts it, to pursue his agenda.

On some less prominent issues in which mutual interests coincide, the GOP and the White House are finding they agree – for instance, on changing mandatory minimum-sentencing laws and replacing housing finance giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Griffin argues that Obama is still trying. The president recently hired an experienced Hill staffer, Katie Fallon, as his congressional liaison, to improve outreach to lawmakers.

Obama should bring in more outsiders who have good relations with both parties, says David Abshire, who came in as "special counselor" to help rescue President Reagan after the Iran-contra scandal. Boehner, too, could use a "wise man," a former member of Congress, as a counselor, Mr. Abshire says.

But short of midterm elections that rebuke the Republicans, it will probably be a slow grind to the end. Obama will have his own party to contend with if he wants to push through big trade deals with Europe and the Asia-Pacific.

Still, some in Washington believe the window, at least on immigration reform, has not yet shut. They encourage Obama to work on the "trust gap" by:

•Continuing deportations, even in the face of tremendous pressure from Democrats to ease up. There may be no better way to show that he's enforcing the law than by reminding Congress that he's doing that now, says Lanae Erickson Hatalsky, director of social policy and politics at Third Way, a moderate Democratic think tank.

•Tasking others with the message that immigration laws are being enforced. The Obama administration has continued a 20-year trend of increased spending and action on enforcement of immigration laws, says Doris Meissner of the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank that studies global migration. The president would do well to have mayors, police chiefs, and even foreign leaders vouch for the effectiveness of enforcement, she says. They would be better-received messengers.

•Continuing to work on the personal. Trust gets built through personal relationships.

Even if the president takes this advice, in the end, it may be self-interest – as it usually is in politics – that pushes the GOP over the immigration finish line. If Republicans want to field a presidential candidate in 2016 who can appeal to Hispanic and Asian voters, they will need to move on this issue sometime before then.

As Griffin would say, if they decide to do that, then Obama will have someone with whom he can do business.