Does everyone need a college degree? Maybe not, says Harvard study.

Loading...

In discussions about “college and career readiness” – one of the education catchphrases these days – the focus is usually on college.

But increasingly, some educators are calling for more attention to the career part of the equation – and questioning whether a traditional four-year college degree is necessarily the best path for everyone.

A new report released by Harvard Wednesday states in some of the strongest terms yet that such a “college for all” emphasis may actually harm many American students – keeping them from having a smooth transition from adolescence to adulthood and a viable career.

“The American system for preparing young people to lead productive and prosperous lives as adults is clearly badly broken,” concludes the report, “Pathways to Prosperity” (pdf).

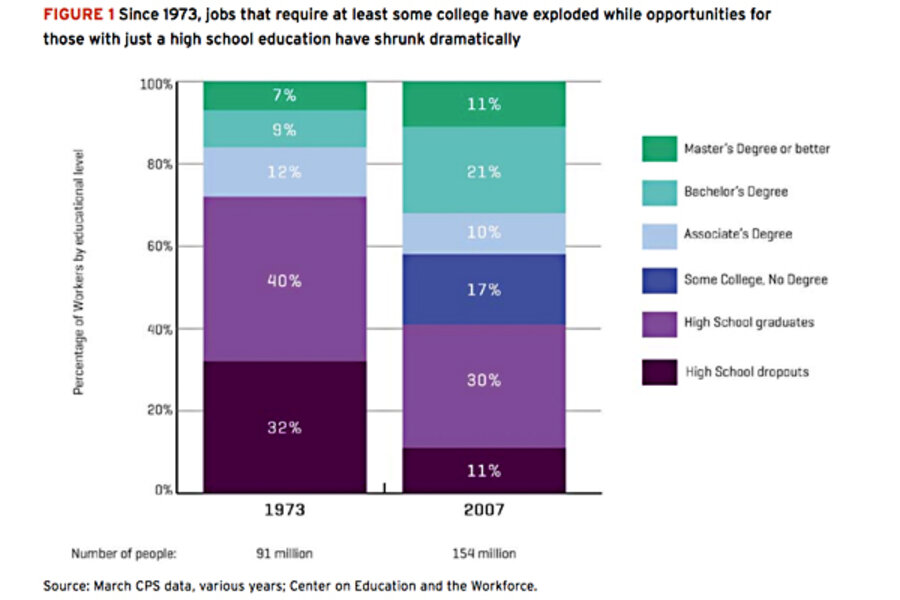

Despite a clear message that college is important – and a pervasive desire among young students to attend college – only about 30 percent of Americans complete a bachelor’s degree by their mid-20s, with another 10 percent completing an associate’s degree by then. A massive effort in recent decades to increase those numbers has improved them only slightly.

“It would be fine if we had an alternative system [for students who don’t get college degrees], but we’re virtually unique among industrialized countries in terms of not having another system and relying so heavily on higher education,” says Robert Schwartz, who heads the Pathways to Prosperity project at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education.

Emphasizing college as the only path may actually cause some students – who are bored in class but could enjoy learning that’s more entwined with the workplace – to drop out, he adds. “If the image [of college] is more years of just sitting in classrooms, that’s not very persuasive.”

Whether students opt for college or not, they need a range of skills to be employable in the long term, so “college and career-ready skills are really no longer two separate tracks,” Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said Wednesday in Washington at an event releasing the report, according to prepared remarks.

While not endorsing the particulars of the Harvard report, Secretary Duncan noted the importance of transforming career and technical programs, in which more than 15 million high school and postsecondary students are enrolled.

The United States can learn from other countries, particularly in northern Europe, Professor Schwartz says. In Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Switzerland, for instance, between 40 and 70 percent of high-schoolers opt for programs that combine classroom and workplace learning, many of them involving apprenticeships. These pathways result in a “qualification” that has real currency in the labor market.

In the US, vocational education has a bad rap, Schwartz acknowledges – and often for good reason, given the poor quality and its traditional role as a dumping ground for poorer students and students of color. And he’s not advocating the sort of tracked systems that Germany and Switzerland have, in which poorly performing students are often pushed into vocational tracks as early as middle school.

In Scandinavia, students follow a common curriculum until Grade 9 or 10 and then choose what sort of path they want to follow. In Finland, where income class is the least predictive of achievement among OECD countries, 43 percent of kids at age 16 opt for a three-year program that mixes work with learning and moves them to the labor market. But they still have the opportunity to go back to higher education later.

Much of the current education rhetoric emphasizes college over career training. President Obama has frequently stated his goal of having the US lead the world in college graduation rates by 2020. “To compete, higher education must be within the reach of every American,” he said in his recent State of the Union address.

But higher education doesn’t have to mean a traditional college degree, the report notes and the Obama administration acknowledges. Many of the growing career fields actually require credentials other than a bachelor’s or associate’s degree.

A Georgetown University study projected 14 million job openings between 2008 and 2018 in the “middle-skill occupations,” such as electricians and paralegals, in which workers need an associate’s degree or occupational certificate.

The college-for-all rhetoric should be broadened, the Harvard report concludes, to become “post-high-school credential for all.”

But the report also says that will take a massive overhaul to a system that, right now, doesn’t do a good job showing kids what the link is between their learning and the jobs to which they aspire.

Employers should be more active in the learning process – whether through internships, visits with students, or brief “try out” experiences – and students need more opportunities to master the kind of “soft skills” likely to help them in the workplace, perhaps through team projects, says Ronald Ferguson, another of the report’s authors and a co-chairman of Harvard’s Pathways to Prosperity Initiative.

The report points to several models in the US that could also be expanded to improve career and technical education. Career academies for high-school students are showing promise in places ranging from Pennsylvania to California. And Project Lead the Way, an engineering curriculum currently serving about 300,000 high-schoolers nationwide, culminates in team projects to solve an open-ended engineering problem.

“If we persist with the illusion that everyone is going to college, then we’re cheating those kids who aren’t going,” Professor Ferguson says. “A majority of the workforce does not have a college degree, and a majority of the things those people do are going to continue not requiring a college degree.”

Staff writer Stacy Teicher Khadaroo contributed to this report.