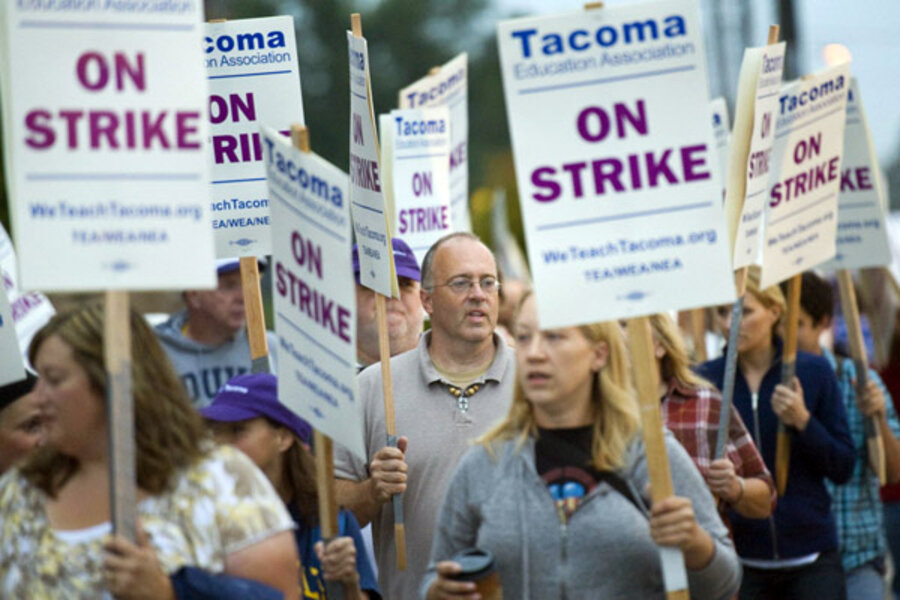

Will striking Tacoma teachers be ordered back to work?

In Tacoma, Wash., teachers could be ordered to go back to work as early as Thursday after two days of strikes have kept 28,000 public school students out of school. The details of a temporary restraining order against the nearly 1,900 striking teachers are to be worked out in court later on Wednesday.

Tensions between unions and school-system leaders around the country are running high as budget cutbacks put pressure on both sides. The teachers’ strikes also highlight some of the education reforms that that have prompted teacher resistance – such as the whittling away of the privileges traditionally bestowed on teachers with seniority.

States such as Ohio, Indiana, and Wisconsin have recently taken away teachers’ collective bargaining powers on most items other than salary.

At issue in Tacoma: class sizes, potential salary cuts, and – most important to some teachers – the school district’s desire to transfer teachers between schools based on criteria other than seniority.

The district wants to be able to move Tacoma teachers around to advance school leaders' goals. They have proposed starting this in the next school year, with a committee that includes teachers being set up to review disputes over transfers.

“The single most significant way to increase academic achievement for students is to match the needs of a class with the best, highest-quality teacher possible,” the district website says. “To do so requires considering a wider range of qualifications than the traditional method of seniority alone.”

Tacoma teachers say they are worried about arbitrary staffing shifts if the seniority policy changes. “A teacher can work five, 10, 15 years in a building, and a new principal can come in and develop their favorites,” second-grade teacher Suzanne Symonoski told the Associated Press.

Education reformers often say that giving school districts more power over school assignment would help decrease inequities in schools, since teachers with seniority often opt to transfer out of schools with the most disadvantaged students.

But there is limited research on the issue so far. In one study of a district that made the policy shift away from seniority, University of Washington researcher Dan Goldhaber concluded that “disadvantaged schools still displayed substantially higher rates of turnover and shares of inexperienced teachers than did more advantaged schools.”

Tacoma teachers also want class sizes reduced, and the district says it will cost $1.8 million a year to reduce each class by one student. They also oppose the district’s proposals to cut salaries or personal days and planning days – which the district says is necessary to meet a state mandate of a 1.9 percent cut in staffing expenses.

Eighty-seven percent of the Tacoma Education Association’s members had supported the strike after working since Sept. 1 without a contract.

Before Wednesday's court ruling, some teachers told local reporters they would defy a back-to-work order, but this may not be a popular decision.

Strikes during a recession with such a high unemployment rate probably don’t get a lot of sympathy, says Eric Hanushek, a senior fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution.

If Tacoma teachers are grumbling over slight increases in class size or decrease in salary, it suggests “they don’t think that the schools should participate in any fiscal retrenchment, says Mr. Hanushek, who supports education reforms that give districts more authority to manage their workforce. "Teachers and unions are a little bit out of touch with what’s going on in rest of society.”

He adds, “There are a lot of pressures on unions today for holding salaries down and changing some of the rules they’ve negotiated over time. Lots of places are reconsidering whether those rules should be in the contracts.”

Associated Press material was used in this report.