School discipline: New US guidelines shift away from zero-tolerance policies

Tough school discipline codes like zero-tolerance policies and mandatory suspensions for even minor infractions may have significant costs and glaring inequities.

That was a major message behind new guidelines issued Wednesday by the Obama administration, calling on schools to seek alternatives to harsh penalties like expulsions and suspensions that rob students of classroom time and may be racially biased.

The guidelines emphasize the need for a positive school climate and supports, clear and appropriate expectations and consequences, and equity in discipline policies. They're a response to a growing body of statistics showing both the costs of harsh disciplinary policies and the frequent inequities in how they’re applied, particularly to black and special-education students.

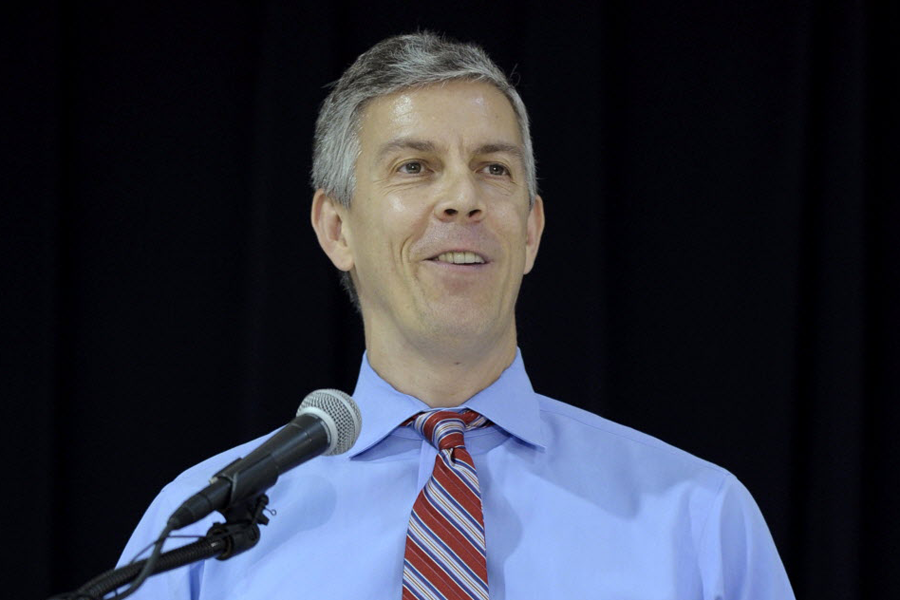

“When carried out in connection with zero-tolerance policies, such practices can erode trust between students and school staff, and undermine efforts to create the positive school climates needed to engage students in a well-rounded and rigorous curriculum,” wrote Education Secretary Arne Duncan in a “dear colleague” letter to school officials. “In fact, research indicates an association between higher suspension rates and lower schoolwide academic achievement and standardized test scores.”

Secretary Duncan emphasized the harsh costs of the overuse of suspensions and expulsions, including students left unsupervised and the loss of needed interventions, mentorship, and classroom time.

In his letter, Duncan cited statistics showing both wide use of suspensions and expulsions and inequity in how such punishments are meted out. African-American students without disabilities are over three times more likely than their white peers to receive suspensions or expulsions, for instance. And special-education students, who make up 12 percent of the student population, make up 25 percent of the students receiving multiple out-of-school suspensions, 19 percent of students expelled, and 23 percent of students receiving a school-related arrest.

Another study found that 95 percent of out-of-school suspensions were for nonviolent, minor problems like tardiness or disrespect, Duncan said.

"A routine school disciplinary infraction should land a student in the principal’s office, not in a police precinct," Attorney General Eric Holder said in a statement.

Civil rights groups, which have long cited similar statistics, lauded the new guidelines for calling attention to such inequities as well as to the academic and social costs of draconian punishment policies. They also commended the practical steps offered to schools to help them put fairer, more effective policies in place.

“This is an incredible moment for folks who have been working on discipline reform for decades now,” says Thena Robinson-Mock, project director of the Ending the Schoolhouse to Jailhouse Track Campaign at the Advancement Project, a national civil rights group in Washington. “For the Department of Education and the Department of Justice to issue this joint guidance and make a strong statement about racial disparities of school discipline – that’s huge.”

Many tough zero-tolerance policies – and increased involvement of law enforcement in schools – began 15 years ago in the wake of the Columbine school shooting. They've increasingly been under attack by education experts and sociologists who see them as ineffective and potentially damaging to students.

In recent years, some districts have started rolling back such policies and allowing for increased discretion by officials and more positive alternatives to suspensions or expulsions.

In November, Florida’s Broward County school district reached an agreement with law enforcement to create an alternative to zero-tolerance policies and entrust principals, rather than school resource officers, with being the primary decisionmakers in student discipline – all in an effort to cut down on the “school to prison pipeline.”

Denver and Buffalo, N.Y., have also been notable for their efforts to implement more common-sense discipline policies, Ms. Robinson-Mock says. “We’ve seen a cultural shift in this,” she says, noting that data have increasingly borne out the academic and social costs of disproportionate disciplinary measures.

In the new guidelines, the Obama administration gives concrete options for districts attempting to reform their policies and build positive school environments, including evidence-based practices like peer mediation, restorative justice programs, collaboration with local mental-health and juvenile-justice agencies, and increased social and emotional learning.

The American Association of School Administrators welcomed the new guidelines, but also pointed out that such big changes will be neither quick nor cheap.

“Superintendents recognize that out-of-school suspension is outdated and not in line with 21st-century education,” said Daniel Domenech, executive director of AASA, in a statement. “They also know the shift toward alternatives can be slow-going. Resistance can make implementing alternatives a difficult course to chart for school leaders. Meanwhile, funds to improve school climate and train school personnel in alternative school discipline can be scarce in today’s economic climate. Unfortunately, federal funding, once available to districts to address school discipline and school climate issues, was zeroed out in 2011.”

The American Federation of Teachers also welcomed the new guidelines, but emphasized the need for resources and support for low-income children in addition to a change in disciplinary policy.

Coincidentally, on Wednesday, the AFT held a symposium looking at school climate and the school-to-prison pipeline. It issued recommendations including training grounded in evidence-based positive school discipline and conflict resolution, more funding for mental-health and intervention services for children, time to analyze and review school discipline data and codes, and increased investments in social-emotional learning and student-support teams.

"The federal government made many positive suggestions, but policies in a vacuum without actual resources and support will not succeed,” said AFT president Randi Weingarten. “Instead of fixating on testing, we should be fixating on making schools safe, welcoming and respectful with meaningful professional development, community schools, real alternatives to suspension and restorative justice programs to empower students to resolve conflicts, and restored budget cuts that have left schools without resources to support students and families.”