How this Supreme Court case could change college affirmative action

Loading...

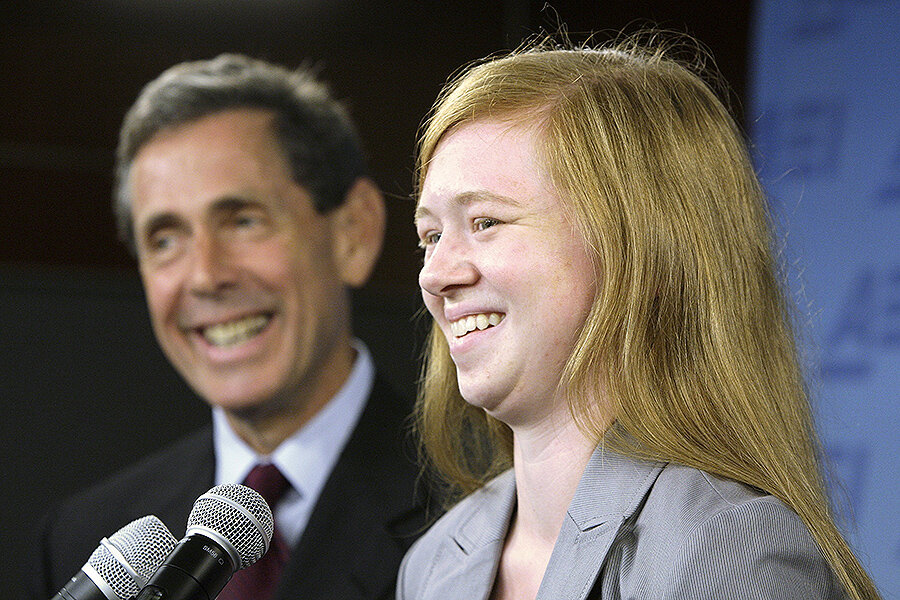

On December 9, the US Supreme Court will once again take up the case of Abigail Fisher, a former applicant rejected for admission to the University of Texas at Austin, whose allegations of unfair racial bias against white candidates stand to challenge affirmative action programs across the country at a time of heightened tension surrounding race and privilege at campuses from upstate New York to Southern California.

In 2013, the Court avoided ruling in the case, which was assembled with the help of anti-affirmative action activist Edward Blum, by vacating a ruling by the Fifth US Circuit Court of Appeals and sending the case back to a federal appeals court. That court's original ruling found Ms. Fisher's lawyers were unable to prove discrimination.

Although some anticipate that the case will be decided on details, such as why Fisher was rejected or how campus diversity would be impacted by a new admissions policy, the justices' willingness to reexamine the case may indicate their diverging views of how to understand equality and diversity in an era when understandings of "diversity" are in flux. Americans decrying "reverse racism" claim that diversity policies are not truly "colorblind," while affirmative action advocates claim the call to "colorblindness" misunderstands the purpose and history of policies meant to level the playing field.

In 2008, Abigail Fisher was a cello-playing, high-achieving suburban high school student who wanted to follow in her father and sister's footsteps to the University of Texas' (UT) flagship Austin campus.

Under Texas law, the UT system guarantees admission to in-state students in the top 10 percent of their class, a highly competitive system that advocates say helps guarantee a fair shot for students at under-resourced schools, many of them black and Hispanic, whose educational opportunities wouldn't let them compete with wealthy suburban students purely on the basis of test scores and easily-quantifiable factors.

Fisher's complaint is with UT's "holistic review" policies. In 2008 92 percent of freshmen were admitted to UT under the top-10 program. To fill the remaining eight percent of seats, admissions officers considered the total of two scores, one for a student's strictly academic accomplishments, and one for a "personal achievement index," which includes criteria such as admissions essays, extracurriculars, and socioeconomic factors like native language, race, and social class.

Fisher was not in the top 10 percent of her graduating class, and was rejected by UT. She alleges that the "holistic review" criteria favor minority students over their white peers in a way that is "neither narrowly tailored nor necessary to meet a compelling, otherwise unsatisfied, educational interest."

In 2013, the Supreme Court upheld the public university's right to hold diversity as a "compelling" interest, meaning the case is largely about how exactly UT evaluates its white and non-white applicants in the "holistic" pool.

In 2003, the Court struck down the University of Michigan's practice of assigning 20 points, on a 100 point scale, to minority applicants. But, according to Forbes, UT's "opaqueness," not giving specific information on how applicants' race is factored into their decisions, may prove the policy's undoing.

"They’ve designed this program quite deliberately to be unaccountable and non-transparent," Cato Institute fellow Andrew Grossman told Forbes. "The hallmark of strict scrutiny is the court has to satisfy itself the program is narrowly tailored and achieves the government’s objectives."

The case could have a far-reaching impact. As a state school, UT is bound to the Constitution's equal-protection clause, which Fisher's team argues that race-conscious admissions policies violate. Other public universities are watching the case closely, as are private schools who receive federal funding, many of which insist on the necessity of their race-conscious policies and hope that Fisher v. University of Texas will be decided on narrow ground less likely to impact them.

But for such a significant case, Fisher's complaint may be on shaky ground. With a modest SAT score of 1180 out of 1600, Fisher's credentials were most likely not up to snuff for Texas' flagship school, regardless of her race, as ProPublica reported in 2013.

Provisional admission was offered to roughly 50 students whose admissions scores, a combination of their academic index and personal achievement index, were lower than hers; the vast majority were white. The personal achievement index considers race among several other factors. 168 minority students with equal or better admissions scores were also rejected.

Fisher was offered admission as a sophomore, if she could maintain a 3.2 grade point average at another Texas university her freshman year, but turned it down in favor of Louisiana State University. She now works in finance in Austin.

But the ideas behind the case are anything but trivial. At stake is the interpretation of the 14th Amendment, which guarantees "equal protection."

'Equal treatment' helped desegregate American schools in the mid-twentieth century. But today, the concept that laws must be "colorblind" is often used to argue against programs meant to help minorities, with anti-affirmative action voices arguing that considering race at all amounts to racism.

"The way to stop discriminating on the basis of race, is to stop discriminating on the basis of race," Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in 2007.

William Leiter, professor emeritus at California State University, Long Beach, also says that equal opportunity may have given way to unequal preference.

"The diversity theory emphasizes that groups are different and they bring different capacities to the academic arena," he told the Wall Street Journal. "That’s a major departure from traditional civil rights law; the 1964 Civil Rights Act said there were not supposed to be any differences between the treatment of blacks, whites, and anybody else."

Critics say that ignores the historical context of the amendment, and the original need for "colorblindness" itself, which was intended to help groups who experienced present or past discrimination overcome those disadvantages. The amendment recognizes "an enormous difference between a white majority disadvantaging minorities and a white majority acting to remedy past discrimination," former University of California, Irvine, School of Law dean Erwin Chemerinsky told ProPublica.

According to researchers from Tufts University and the Harvard Business School, white Americans now feel that they face more discrimination they believe black Americans do. "Whites See Racism as a Zero-sum Game that They Are Now Losing," the authors titled their paper.

As Georgia State University law professor Eric J. Segall notes in an op-ed for the Los Angeles Times, conservatives' opposition to affirmative action puts them at odds with traditionally conservative principles: to force UT to change its system by Supreme Court ruling would, for example, overlook a historical preference for states' rights, and ignore the historical context of the 14th Amendment. Conservative judges often claim original intent as a value, in opposition to allegedly "activist" judges who interpret the Constitution through a modern-day lens.

Editor's Note: In 2003, the Supreme Court upheld the University of Michigan's law school admissions policies. However, it ruled against the undergraduate admissions practice of assigning 'points' based on diversity. An earlier version of this article misstated the credentials of students evaluated for the University's provisional acceptance program. Students were accepted or rejected on the basis of admissions scores: a combination of academic and personal factors.