How one poor Brooklyn preschool is competing with the best

Loading...

| BROOKLYN, N.Y.

This story was written by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

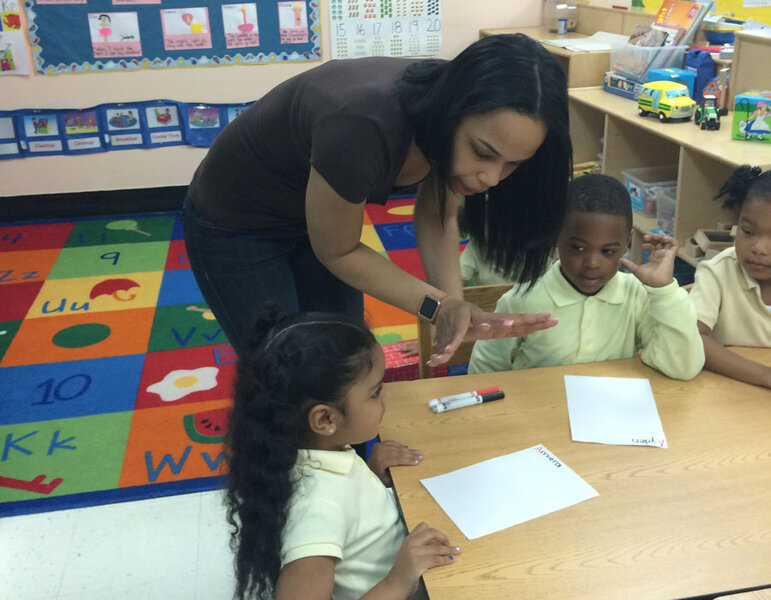

At the Audrey Johnson Day Care one sunny April morning, preschoolers were discussing how seeds grow into plants.

The teacher asked them, “Is the sun natural light or artificial light?” A few of the 4-year-olds answered, “Natural light.” “Good job. Kiss yourself,” the teacher instructed the class.

They all kissed their hands.

Student engagement and positive reinforcement like this, experts say, is a sign of a quality prekindergarten program. The Brooklyn school is one of hundreds of preschools across New York City to receive high marks, according to recent results of the Early Childhood Environmental Rating Scale (ECERS).

But what makes this center unusual is that it is serves Bushwick, a high-poverty community in which public elementary schools don’t do well on state and city tests. It’s one of the few schools in a high poverty neighborhood to do so – and it’s providing higher quality education than many of its pre-K counterparts in wealthier school districts.

“We are closing the gap,” said Alexandra Rick, an Audrey Johnson teacher. She has taught in private schools on the Upper West Side of Manhattan and in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, two of New York City’s most affluent areas. Students there, she said, enter with rich vocabularies, have lots of books at home, and are routinely enrolled in swim, soccer, and music classes.

Most of her Bushwick students come from homes in which little English is spoken and income levels are low, she said. She tries to build their vocabulary through conversation and by encouraging their parents to take them to the library and museums. “The pre-K age is crucial to their development,” she said. “They are sponges now.”

Audrey Johnson and schools like it point to one of the most promising ways to narrow the achievement gap between high poverty children and their middle class counterparts – by providing high quality education before children start kindergarten.

“Children in low-income houses start anywhere from a year to 18 months behind in language and mathematics and social and emotional development,” said Steve Barnett, director of the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER). “Half the achievement gap we talk about in the third grade and beyond starts before they even get in the door of kindergarten.”

In 2014-2015, state funding for pre-K shot up more than $553 million over the previous school year, according to NIEER’s 2015 State Preschool Yearbook, making it the third year in a row that state pre-K funding has increased nationally. Almost two-thirds of the current increase is accounted for by New York where Mayor Bill de Blasio has pledged to provide preschool for all eligible children, an estimated 73,000 youngsters.

Getting all those youngsters in a prekindergarten program is a critical first step, experts say, but improving the quality of those classes, including better training for teachers, will take time in New York and elsewhere.

“You can’t just say, ‘We’ll hire good teachers.’ They are rarely good their first year,” says Mr. Barnett, who estimates it will be closer to 10 years before there is a noticeable improvement in the New York City system as a result of the expansion. “You have to transform the adults in the classroom and that doesn’t happen by magic.”

Evaluating the program is important, said Barnett, so that schools can see where they need to improve and education officials can see if there are systemic problems. “They are really powerful tools for improving practice. I call them the GPS for improving practice,” he said. “It’s not for blame, as in who got us lost, but how do we find our way and achieve the goals we want to achieve.”

In New York City, educators rely on ECERS data, which examines three main areas: health and safety, opportunities for children to develop social-emotional skills, and educational opportunities (like teachers working on vocabulary development). In 2014-15, a team of evaluators inspected 650 city public prekindergarten programs, up from 200 programs typically evaluated during an academic year, said Debby Cryer, one of the designers of the ECERS scale, which is used nationally.

“What we are looking for is what is needed for their success,” Ms. Cryer says. “It doesn’t help to spend time teaching them to read the words if they don’t understand the words. Schools think they should be getting them to read and that’s foolish, but we see a lot of it today.”

There’s a misconception among some teachers and parents, said Cryer, that if children are taught reading and writing earlier, they’ll know it better. “You can’t push them ahead,” she warns.

Signs of improvement

In her last few years evaluating New York preschools, Cryer said she has noticed a dramatic improvement in programs, which she attributes to more professional development for teachers. “They weren’t meeting the needs of the children particularly well, but they are getting better and better,” she said. An ideal score is 5 (out of a possible 7), she said. A score of 5 indicates children “are well-protected, learning what they need to learn, and have a strong sense of themselves,” she said.

For the most part, the ECERS results echo achievement patterns in New York — low-performing districts have low-quality programs and high-performing districts have high-quality programs. The district with the highest average score (4.59) is District 26, an upper middle class area in Queens that includes Little Neck and Jamaica Estates, while the lowest average ECERS scores (3.38) belong to District 7 in the South Bronx, among the city’s poorest neighborhoods.

There are exceptions to this pattern — like Audrey Johnson. When it was last evaluated in 2014, the program averaged a score of 4.5 out of 7 in three areas: health/safety, opportunities for kids to develop social-emotional skills, and educational opportunities, putting it in the top third of all preschools.

Audrey Johnson Day Care is hardly a newcomer to early education. The facility has been offering free or low-cost child care to the community since 1971, getting funding from the New York City Administration for Children’s Services. The de Blasio prekindergarten expansion allowed the center to offer another two public pre-K classes, each with less than 18 students and two teachers, for 4-year-olds in 2015, bringing the school to four pre-K classes and about 60 students.

Audrey Johnson has partnered with Columbia University on a math program that sends coaches into the classroom and with New York University for a literacy initiative that allowed the school to create a lending library for families. The center recently received a grant from the Citizens Committee for New York City to put planters in each room, according to Julie Dent, the executive director of Audrey Johnson.

Each classroom has puppets, instruments, a block area, water table, instruments, a library, computer, and new crayons — all the equipment commonly found in pricey private preschools. If children are feeling blue or just need a break, they are encouraged to sit in the cozy area (a beanbag). Students are chatty and eager to ask questions.

“Our students are well prepared,” said Dent. “Some go to gifted programs. They can compete with anyone.”

The children feed into Public School/Intermediate School 384 (P.S./I.S. 384), located across the street, which enrolls students up to 8th grade. All the students qualify for free lunch, a benchmark of poverty. Less than 20 percent of the school’s students met state math or reading standards last year, according to test results for grades 3 to 8, listed on the state education department’s website.

P.S./I.S. 384 Principal Phyllis Raulli says that students from Audrey Johnson are better prepared for school than those who come directly from home, but so are children from an in-house prekindergarten (it earned 4.3 on the ECERS ratings). In the past two years, she has noticed that the academic readiness of students who attended public preschools has increased — a sign, she said, that the quality of these programs is improving.

“They do have the vocabulary in subject areas, especially with numbers and shapes,” says Ms. Raulli. “They know what perpendicular means. They know what geometry means. It’s amazing. It’s not a textbook, it’s all hands on.”

Related: Notable research on pre-kindergarten education

Whether this preschool success will help these students perform better on New York state tests remains unknown. It’s impossible to determine if children who score poorly — or well — on state exams attended preschool without tracking individual students, who often move from one district to another, said education officials. Many students who attend preschool may move out of Bushwick. Because of continuing gentrification, the neighborhood has experienced high turnover in the past few years, says Assistant Principal Marilyn Cruz.

One thing that is clear, said both Raulli and Ms. Cruz, is that preschool improves kindergarten performance. “Our students that come with pre-K education definitely do better in kindergarten than those that come from home,” Cruz said. “It’s very visible in how they hold themselves.”

Changing expectations

Bushwick elementary schools have long struggled. Districtwide, only 21 percent of elementary and middle school students were proficient in math and 19 percent were proficient in reading, state test results for 2015 show. Yet the preschools do quite well. According to ECERS data, prekindergartens in the district have average score of 4.2, making them among the top programs in New York City.

The disconnect between pre-K and elementary/middle school performance is not uncommon, experts say, noting that in the past, the standards for vocabulary and social-emotional development in even good quality pre-K programs weren’t high enough. These preschools had been measured by an easier standard if they were measured at all, as many schools districts didn’t do evaluations.

“Our expectation isn’t you are doing fine for this neighborhood,” says Barnett. “The expectation is how you look against all the kids in New York State. That doesn’t mean pressuring kids, but there is a difference between talking about yellow flowers and forsythia.”

Pre-K provides other advantages, like parent involvement and small class sizes, that dissolve as children progress through elementary school.

Dent said parent involvement has been key to the Audrey Johnson Day Care’s success. Parents visit the classrooms at least once a month, she said, noting that the school also has an open-door policy that allows parents to enter the classroom unannounced at any time. Parents are encouraged to voice their opinions; the school provides a suggestion box for this purpose. And Audrey Johnson goes beyond day care by offering programs for parents. The school holds English classes for adults some evenings, and once a week parents and children are invited to join a 5 p.m. exercise class in the lobby.

“The parents play a vital role in decision-making here,” said Dent. “We do a lot. You have to.”

There is no marked distinction between the quality of preschool in private centers versus the ones in public elementary schools in New York, according to the data. Nationally there is also no pattern, said experts.

“You can have incredibly great early childhood programs in low-income areas and incredibly poor ones in high income areas,” said Cryer.

Dent recruits teachers from the community, even employing graduates of Audrey Johnson, like teacher Nicole Miller. “I feel like I’m helping my community succeed,” said Miller, who was a preschooler at Audrey Johnson about 20 years ago.

After the 4-year-olds kissed themselves, she asked them questions like, “Can I bake a plant?” The children giggled and said, “No, you need seeds.” They stretched up high, pretending to be plants, then sorted seeds before selecting individual activities, such as painting or building with blocks. Giving students choices like these and asking questions helps build reasoning skills, said experts.

Barnett suspects more city prekindergarten programs, including Audrey Johnson, will earn higher grades as New York’s universal pre-K program improves, which will help close the gap in education.

“We are hoping we can ratchet up the quality of pre-K to more effectively supplement what is happening in the home,” says Bruce Fuller, an education professor at the University of California, Berkeley. “Even with stellar levels of quality, it’s not going to overcome the disparities in the home and disparities across classes, but it’s a start.”

This story was written by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education and is affiliated with Teachers College, Columbia University.