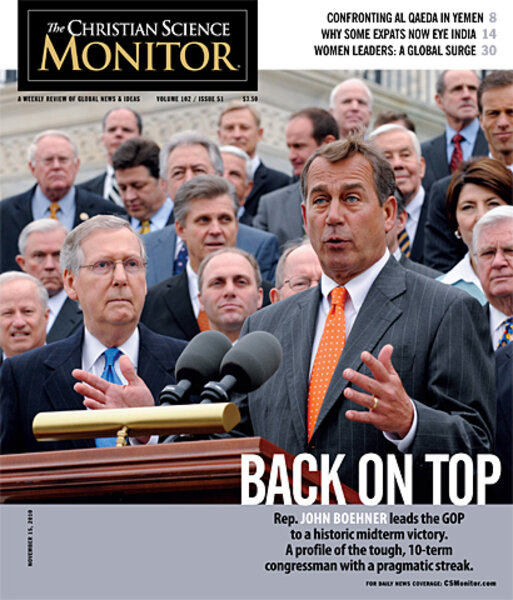

Speaker-to-be John Boehner: More confrontation or a hint of compromise?

Loading...

| Reading, Ohio

He grew up here in a small house with 11 brothers and sisters – a brood so big that when a young John Boehner first brought his girlfriend (and future wife) home for dinner, he told her that all the kids in the backyard were neighborhood friends. In fact, they were his siblings.

He worked at the family bar, the one with the moose head still hanging on the wall, to help pay his tuition to Roman Catholic high school by mopping floors and waiting on tables. Later he would take over a struggling plastics container business after the death of its owner, a baptism in small-town capitalism that shaped his views of the role of government in business.

As Republican House minority leader Boehner prepares to become the likely next speaker of the US House of Representatives in January, he will draw on his varied experiences growing up in this blue-collar town outside Cincinnati, as well as his two decades in the marbled halls of Congress, to guide him through what may be one of the toughest tenures as House leader in modern times. He will have to navigate a bumper crop of tea-party-infused GOP freshmen as well as battle-hardened Democrats at a time when the American electorate seems unusually impatient with its political leaders.

Boehner professes to be up to the task, in part because of what he learned in the sharp-elbowed world of saloons and siblings of his youth.

“You had to learn to deal with every character that came through the door,” he said in a recent interview in his House leadership office. “Growing my business, building my team, and serving in this institution for almost 20 years, I think I understand the diversity we have around here and how to manage it.”

Boehner will certainly bring fresh style and substance to the job. Though a committed conservative, he is not an ideologue or firebrand, despite the rhetoric he unleashed toward the White House on the campaign trail. Boehner is pragmatic, typically laid back, and habitually inclined to listen. He watched as House Republican leaders in his day, notably former House Speaker Newt Gingrich and majority leader Tom “the Hammer” DeLay, centralized power in their offices and made themselves the story – and, as a result, some say, fell before their time.

Behind the scenes, across the aisle

Boehner is inclined to work quietly behind the scenes. His instinct is to compromise, but he is not a bipartisan crusader and won’t get out in front of what the Republican caucus is prepared to accept. His public image is that of the consummate Capitol Hill pol – the sharply dressed, smooth-talking lawmaker who once played as many as 100 rounds of golf a year while hitting up lobbyists for big checks.

Former GOP majority leader Dick Armey sees him as Dean Martin without the piano – someone who makes everything look easy. “He is a man wholly without guile,” says Mr. Armey. “I don’t think John Boehner has ever spent a moment of his life in intrigue with respect to anyone else. He is a serious workman and, unlike some previous speakers, doesn’t require attention. He’ll get the job done with little fanfare. It’s not about him.”

Now in his second rise up House leadership ranks, Boehner has built a staff on and off Capitol Hill and a network of loyalists and donors so durable that it has a name: Boehner Land. He is often caricatured for the color of his skin – a famously deep tan – but he may be more notable for the thickness of his skin. He’s a survivor of fierce intraparty power struggles. If he holds grudges, it doesn’t show. He likes to quote Reagan: Disagree without being disagreeable.

Boehner has been willing to reach across the aisle. In the first year of the George W. Bush administration, he forged an unlikely alliance with Sen. Edward Kennedy (D) of Massachusetts and Rep. George Miller (D) of California to move President Bush’s top domestic priority: education reform. Notably, he did so over the strong opposition of powerful GOP colleagues.

But Democrats insist that Boehner’s past record of bipartisanship has been more than eclipsed by his switch to relentless opposition in the Obama years. “Our work together on No Child Left Behind was one moment in time that has itself been left behind,” said Mr. Miller, now chair of the House Education and Labor Committee, in a statement. “Everything since has been partisan opposition to issues of great importance to America’s middle class.”

Under Boehner’s leadership, House Republicans counted it a victory to unanimously oppose the Obama administration’s $814 billion stimulus plan, health-care reform, financial regulation, and small business tax cuts. On the House floor, he turned “Hell, no…!” into a mantra during the health-care debate and, more recently, while campaigning for Republican candidates. President Obama, in turn, repeatedly labeled Boehner an obstructionist out of touch with the needs of the middle class.

Will it now be confrontation or compromise?

What he would do with the gavel

When former Rep. Dennis Hastert (R) of Illinois was speaker, he set as a principle that he would only bring legislation to the floor if it had the support of “a majority of the majority.” Boehner says he would not insist on that threshold, noting that he wants to open up the legislative process. That would make the chamber more democratic – with a decidedly small "d" – but it would also come with risks. Democrats could use amendments to maximize tough votes for the GOP majority – a standard tactic for the party out of power – and put vulnerable freshmen at risk in 2012.

“I said in 1991 and I’ll say it today: What do we have to fear in allowing the House to work its will?” Boehner said in the interview. “All 435 of us represent 650,000 to 700,000 Americans. Every member ought to have the chance to represent the views of his or her constituents.”

To do that, Boehner would have to direct the Rules Committee – which in recent years has grown more restrictive in offering opportunities to the minority – to change course. In a speech to the American Enterprise Institute last month, he called on Congress to rewrite the Budget Act of 1974 to make it easier to rein in deficits and pass spending cuts. He also called for a more open debate process and moving power out of the speaker’s office to committees. “In too many instances,” he said, “we no longer have legislators; we just have voters.”

He ended that speech by quoting Nicholas Longworth, a former House speaker from 1925-31, who, like Boehner, was from Cincinnati. Mr. Longworth aimed to make the House more effective – to become, he said, “the most dominant legislative assembly in the world.” Boehner called for empowering all members through committee work and possibly amending bills on the floor. “We should open things up and let the battle of ideas help break down the scar tissue between the two parties,” he said.

Boehner and Obama

Despite their considerable differences, Boehner insists he could work with Mr. Obama. He says he and the president are “not close, but we get along fine.”

“I’ve made it pretty clear that I came here to fight for a smaller, less costly, and more accountable government; that we need to focus on getting the economy moving again and creating jobs in America,” he said. “And to the extent that he’s willing to work with us on that agenda, I welcome the relationship.”

But Boehner’s rapport with Obama will be critically affected by the changing tenor of the House Republican caucus. When Boehner said on CBS’s "Face the Nation" on Sept. 12 that he is open to voting for an extension of the Bush tax cuts that excludes Americans making more than $250,000, if that’s the only option, House Republicans balked. GOP whip Eric Cantor (R) of Virginia fired off a statement the next day opposing that approach without mentioning Boehner. Boehner quickly dropped the point.

Boehner also embraced many tea party themes during the campaign, which he will now be expected to follow through on. On Sept. 23, House Republicans released a 45-page “Pledge to America” that called, among other things, for the repeal of “the government takeover of health care.” Many tea partyers have repeated their intent to do so in the wake of the election as well as to push for a huge reduction in government spending. Obama has said only that he will consider “improvements” in the health-care legislation and is willing to seek “common ground” on budget cuts.

Boehner maintains that he will be able to work with the new lawmakers in his caucus, in part because he shares many of their values and route to power. The tea party candidates, he said, included a “lot of businessmen and women – a lot of really, well-qualified, sincere people who’ve looked up just like I did 20 years ago and decided it was time to get involved.”

The accidental speaker

Boehner’s path to Washington was not obvious or even likely. In the neighborhood where he grew up, it’s a steep walk from Andy’s Café, the family bar where he worked as a teenager, to the two-bedroom home that was a mail order from Sears, Roebuck. A small, three-bedroom addition, built by Boehner’s father and twin uncles, helped ease the space crunch for the family, but the boys still often slept outdoors, weather permitting.

High school was a pivotal time for Boehner, exposing him to new worlds and social classes. A photo of a class field trip to Washington, D.C., shows a young Boehner standing out in a flashy madras jacket.

“I’d still wear that jacket, if I had it today,” he said. “High school was one of those important points, mostly because I had grown up in a very blue-collar town. I went to high school and met a bunch of guys from other parts of town, who were clearly a lot more affluent than what I grew up in, and it just opened my eyes that there was just more out there.”

He was, by his own account, not a great student, but found a niche in team sports like football, where he was best known as a center, or long snapper, for punts and extra points. Football coach Gerry Faust recalls Boehner’s willingness to take the field, injured, when needed in big games. “He is a team player. He wanted us to be successful,” he says.

“He understands what it means to be poor,” adds Mr. Faust, who established Archbishop Moeller High School as a state football power before moving to coach at the University of Notre Dame. “Nothing came easy. He had to work for what he got.”

Boehner's wife, Debbie, recalls her first dinner at the Boehner house as a highly regimented affair, with a whirl of new faces, sacks of potatoes, jumbo cans of green beans, and an assigned task for every family member.

“It was tough to go home and tell your dad: ‘I think I might marry a Catholic, he’s one of a family of 12, and he’s a janitor,’ ” she said on a tour of Boehner sites in Reading.

Over time, Boehner put himself through night school at Xavier University, working a variety of odd jobs, including as a janitor, and later got involved in a plastic container business that he built up after the owner’s death. Public office was nowhere in sight.

Businessman turns 'reluctant' politician

Then, in 1977, he got involved in his local homeowners’ association. He ran for township trustee and, later, at the urging of a lobbyist for Armco, now AK Steel, Boehner ran and served two terms in the state legislature. “When he ran the first time, I thought he was crazy,” Debbie says.

Boehner describes himself as a “reluctant warrior” in politics. “It was not really what I wanted to do,” he said in the interview. “But I was frustrated with government, thought it was too big, spent too much, and was out of control, and as someone who was succeeding in the free enterprise system, I believed that the government was choking the goose that was laying the golden egg. And it still is, even worse.”

When the local congressman got into trouble, Boehner sought and won his seat. As a freshman in 1991, he was one of the brash newcomers who attacked congressional perks and abuses. He also pledged not to carve out earmarks or pork projects for his district – a position that the GOP caucus only adopted, tentatively, this year. Minority whip Newt Gingrich drew him in to help draft the 1994 "Contract with America." When Gingrich became speaker, Republicans selected Boehner to chair the GOP conference. He was ousted in 1998, the year Gingrich resigned his post after Republicans unexpectedly lost five seats in the midterm voting.

The election of George W. Bush in 2000 gave Boehner another key shot at leadership, this time as chair of the committee responsible for the president’s high-profile attempt to reform education. The only trouble was, many House Republican leaders were lining up against the bipartisan plan emerging from Boehner’s panel. “It was a comeback for Boehner to get chairmanship of that committee, and suddenly there was this issue of his going right back into Siberia, probably forever,” recalls Sandy Kress, Bush’s education adviser.

A wink from George W. Bush

At one point, Boehner was playing golf with David Hobbs, the Bush administration’s chief legislative lobbyist, who told him the blunt reality. “You’re in big trouble; leadership is in revolt, you should expect a call from Dick [Cheney],” Boehner recounts.

The White House summoned House GOP leaders to a meeting three days later. Boehner’s plane was late, and the meeting was well under way when he arrived. “[House Republican whip] DeLay was just dumping all over where I was going with this bill, and then [majority leader Dick] Armey chimed in and then [Speaker] Hastert, who had been an even-handed player through the whole thing, chimed in with DeLay and Armey,” Boehner says. About this time, he adds, the president gave him a wink, then another. Boehner presented his case for reform, and at the end, Bush said: “I’m with Boehner; this meeting is over.”

According to Mr. Kress, who was in the meeting, No Child Left Behind would have never made it through Congress if Boehner had bailed on the plan. He says one of the arguments Boehner made was the importance of not reneging on his agreement with Miller, the Democrat. “He said: ‘I made a commitment and I’m going to honor it,’ ” Kress recalls.

The question now is how much cross-aisle dealing Boehner will be doing when the atmospherics in Washington are so different. To get anything done, one thing seems certain: He will have to be as supple in the halls of Congress as he is on the golf course, where he swings right-handed and putts left-handed.