America's new isolationism

Loading...

| Washington

As President Obama pressed earlier this month for congressional authorization to use force against Syria over a gruesome chemical weapons attack, one reader's comment on a Politico story assessing the president's prospects captured the mood of a fatigued and inward-looking America.

"Losing the vote is the best thing that could happen," the reader said. "Then we can sail away from the Middle East and mind our own business."

After a decade of wars in the Middle East and Muslim world, and after a "great recession" that sapped the United States economically and psychologically, Americans appear ready to board a sloop and forget about the rest of the world.

In one survey after another, the percentage of Americans preferring the US to "stay out" of world affairs climbs to record levels – in one it's at a seven-decade high. Polls taken during Mr. Obama's 10-day campaign in September for public backing of his plan for punitive military strikes against Syria's Bashar al-Assad revealed deeper resistance to action in Syria than to other unpopular presidential initiatives for intervention in recent decades.

Moreover, surveys find that Millennials in particular eschew global engagement – suggesting the trend could have an effect on America's role in the world for some time to come. Yet while some experts and pundits trumpet the advent of a new isolationism, others say not so fast. Libertarians and progressive internationalists alike say that, after the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, which cost the US tremendous blood and treasure even as they cost those countries even more, Americans have turned resolutely noninterventionist.

But that doesn't necessarily mean Americans want to disengage from the world. What they do want is for America to work with other countries, not to go it alone. It's America as Mr. Fix-it – especially when the solution involves military intervention – that Americans have soured on.

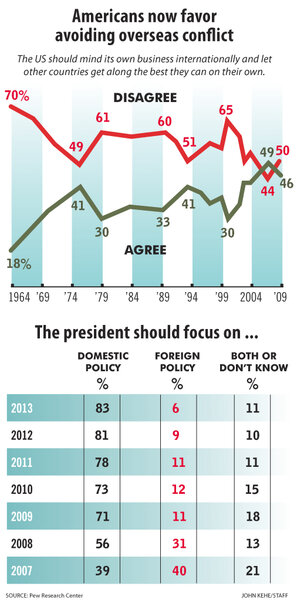

"Americans are very gun-shy these days. They want to tend their own gardens," says Andrew Kohut, a national pollster whose Pew Research Center found in July that nearly half of Americans – 46 percent – prefer to see the US "mind its own business" while letting other countries "get along as best they can on their own."

Those disagreeing with the temptation to stay out of the world's affairs still come out on top – barely – at 50 percent. But that marks a 15-point drop from a post-9/11 surge in support for international engagement that Pew and other polls registered.

What happened after the rise in interventionist sentiment in the early 2000s was a decade of war – the Afghanistan conflict becoming the longest in American history – that left people disillusioned and doubtful that military ventures are a solution to the world's problems.

One reason this prevailing American mood is associated with isolationism is that today's context in many ways parallels the post-World War I era, when isolationism was at its zenith. In the 1920s and '30s, Americans' revulsion at the violence of the Great War and their bewilderment over the unsettled power struggles of Europe fed a desire to stay home and avoid conflicts on the Continent.

Substitute the Middle East today for the Europe of about a century ago, some historians say: It plays the same role of catalyst for a turning inward that Europe played for Americans after World War I.

"Americans in the 1920s and '30s were experiencing a deep war weariness, and the murky, hard-to-understand and seemingly intractable problems of Europe reinforced the feeling that there was no good reason to get involved there again," says Christopher Nichols, an expert on US foreign interventions and isolationism at Oregon State University in Corvallis.

"There are parallels with how Americans today feel about the Middle East, especially after the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan," he adds. "It seems murky, it's hard to understand, and experience has reinforced the thinking that we can't solve their problems by intervening."

In both cases, there was a strong impulse "not to go abroad when there are things we need to take care of at home," adds Dr. Nichols, whose book "Promise and Peril: America at the Dawn of a Global Age" explores the American tension between activism abroad and tending to matters at home.

Nichols sees another similarity between the post-World War I era of isolationism and today: In both cases the political extremes of the noninterventionist spectrum, from conservative foreign-policy "traditionalists" to the peace lobby, form a surprising alliance against US "entanglement" in foreign conflicts.

Today, libertarian Sen. Rand Paul (R) of Kentucky and tea party favorite Sen. Ted Cruz (R) of Texas argue against Syria intervention with rhetoric that sounds much like that of leftist Sen. Bernie Sanders (Ind.) of Vermont, the antiwar group Code Pink, or former US Rep. Dennis Kucinich, who railed against the 2011 US intervention in Libya.

"There is evil on both sides and ... I see no clear-cut American interest" at stake in Syria's civil war, says Senator Paul.

"It's not the job of US troops to police international norms" pertaining to chemical weapons, says Senator Cruz.

"The American people share the president's concerns about chemical weapons in Syria and the brutal Assad dictatorship," says Senator Sanders. "But, in overwhelming numbers ... they want those issues addressed diplomatically ... not by unilateral military action."

All three senators were poised to vote "no" on Obama's request for authorization to use force in Syria.

"We see the outer edges of the American left and right coming together today in opposition to intervening in Syria, just as we saw the pacifists and isolationists of the 1930s come together to oppose all intervention in foreign conflicts and even in favor of global disarmament," says Nichols.

The cooperation of disparate groups was exemplified 80 years ago by the anti-interventionist union forged by Idaho's Sen. William Borah, an icon of the "no foreign entanglements" camp, and the antimilitarist Women's International League for Peace and Freedom.

In the late 1940s, right after World War II, the US engaged in a fierce debate over how much to participate in the postwar world. One of the leaders of the non-involvement movement was Robert Taft, a powerful senator from Ohio with rimless glasses and wispy hair who was known as "Mr. Republican."

Taft virulently fought US participation in groups such as the newly formed North Atlantic Treaty Organization, which he believed would inevitably lead to the US being forced to police the world and create a "profession of militarists." He instead called for the US to retreat to a "Fortress America." Taft lost his bid to be the GOP presidential nominee in 1948 to Thomas Dewey, from the internationalist wing of the party, and later to Dwight Eisenhower in 1952.

Taft's worldview is a reminder that historical comparisons are enlightening in how they underscore the cycles of isolationist impulses over the course of American history. But the parallels only go so far, especially since virtually everyone recognizes that his vision of an America hidden behind a stockade, disengaged from the world, would no longer be possible today.

Yet all that doesn't rule out the possibility that America might be witnessing the rise of a new isolationism: one rooted in the perceived failures of two Middle East wars and dubious of the moral argument for American foreign intervention, yet which recognizes the necessity of global interaction, particularly to foster international trade.

"What we're seeing today is something like isolationism, but not to the extent of the 1920s and '30s," says James Meernik, an expert in the political use of military force in US foreign policy at the University of North Texas in Denton. "That's just not really possible for the US anymore."

A globalized economy, America's trade relations, and recognition of the international dimension of a growing number of issues – from terrorism to climate change – mean "people recognize we can no longer just close up shop and forget the world," he says.

But the experiences of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan – as well as the intervention in Libya, which seemed like a success until Islamist militants in Libya's post-intervention chaos launched the Benghazi terrorist attack that killed four Americans – embittered Americans on military involvement, especially in civil wars in the Middle East.

The deadly September 2012 strike on the US diplomatic mission in Benghazi that claimed the life of the US ambassador to Libya, Christopher Stevens, was all the more bewildering because of Mr. Stevens's status as a hero of the Libyan opposition. The attack "brought a focus to the confusion Americans feel in general about our interventions in the Middle East," says Dr. Meernik, accentuating longstanding doubts about whom the US is trying to help in the region's civil wars, who the "good guys" are, and whether by its presence the US is actually defeating Al Qaeda or empowering it.

"What we have now is a deep reluctance to get involved in complicated conflicts, particularly in a region that has given us so much trouble," Meernik says. "I don't think it's surprising that we're now seeing a retrenchment, a turning back to US domestic issues, and a preference for staying out of others' problems."

On a rainy fall day in Boston, Dinorah Rosario is standing in front of the Berklee College of Music, where she goes to school. Ms. Rosario, a viola player who is studying music education and performance at the jazz and contemporary music college, doesn't think the US should be the world's plumber or policeman – someone always trying to fix things.

"We have more than enough problems for ourselves," says Rosario, a second-year student from Springfield, Mass. "I'm not saying it's bad to step out and help another country, but we need to focus on our own problems here."

She singles out unemployment, college financial aid, and health insurance as the issues that are uppermost in her mind. But Rosario, who has a cousin who served in Iraq, also harbors a more visceral objection to military intervention: Americans shouldn't have to see their "loved ones taken away because of someone else's problem in another country."

Rosario represents a generation that, perhaps surprisingly, wants to avoid the world's affairs more than most Americans. Even though Millennials – those ages 18 to 29 – grew up in a globalized world, many of them are interested in taking a "breather" from international affairs, especially when it comes to entering conflicts.

"For many decades there's been something around a two-thirds majority of Americans who said the US should maintain an active role in world affairs, although it has been moving downward," says Steven Kull, director of the University of Maryland's program on international-policy attitudes. "But more recently we're seeing concerns that America has too big a footprint in the world, particularly in the Middle East, that our presence [in the region] has been ineffective and if anything has created a backlash. And we have some indication that Millennials have these attitudes more than the rest of the population."

Last year, a survey by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs found that more than half of the 18-to-29 age group – 52 percent – said they preferred to see America "stay out" of world affairs. That was considerably higher than the 38 percent of all Americans who chose "stay out" over "play an active role," although Dr. Kull points out that even the 38 percent marks a seven-decade high.

In the end, Millennials' apparent reluctance to get entangled in other countries' affairs may be understandable. Experts note that they grew up seeing America attacked by terrorists and then respond by going to war almost perpetually ever since. They've also been shaped by the Great Recession, which produced years of political bickering over budget deficits and rising debt, exacerbated by expenditures on foreign military ventures.

Nor was the global financial meltdown just an abstraction to young adults. It became real in the form of a weak job market and, for many, falling living standards. These factors, along with a strong belief in the futility of using military muscle, help explain a turning inward after a burst of interventionism after 9/11.

"We might be able to make a small impact, but it won't last," says Daniela Oliveras, a college student in Boston who's from Southbridge, Mass. "Look at the past: We've seen what happened other times when we have gone into countries and tried to tell them to do things like we do. It doesn't work."

Such pragmatic perceptions as to the ineffectiveness of American intervention – in particular in the Middle East – are a long way from the sentiments of American exceptionalism and moral obligation found in Obama's reasoning with the American people for airstrikes in Syria. Obama evoked presidents before him – Ronald Reagan's vision of America as "the shining city upon a hill," for instance – when he reminded viewers that America's willingness to "act," indeed, that "we should act," to confront the world's evils is "what makes us exceptional."

Obama's words drew a rebuke from Russian President Vladimir Putin, who took to the editorial pages of The New York Times to respond to his US counterpart: "It is extremely dangerous to encourage people to see themselves as exceptional, whatever the motivation."

Others say such ringing references to America's special role in the world increasingly alienate Americans who reject anything that sounds remotely like unilateralism. "If exceptionalism is the rationale for intervention, it runs aground on the shoals of multilateralism," says Oregon State's Nichols. "Calls to action based on America's uniqueness sound inconsistent with working with the international community, and that's confusing to Americans."

But the president's words – and calls to action – still stir some Americans. "We're America. That's what we do," says Tre'Maine Rather, an employee at Boston's Hynes Convention Center, explaining his support for Obama's call for airstrikes on Syria. "We have to take some action to help them."

A sense of moral obligation and a conviction that America should intervene because, as the world's sole global military power, it can, lie at the foundation of Anthony Chima's support for US action in Syria. Mr. Chima, who moved to the US as a young adult in 1981 with memories of the Nigerian-Biafran war of the late 1960s still vivid, points to humanitarian disasters in which the US failed to intervene, like the Rwandan genocide of 1994.

"We cannot stand still and watch," says the Nigerian native, who now lives in Mobile, Ala.

Yet such sentiments are in the minority – as Obama discovered as he and his proposal for even a "modest effort" in Syria ran into a wall of skepticism from the American people.

For a historian like Boston University's Andrew Bacevich, that wall was built over the course of more than three decades of US intervention in the Middle East – from Reagan's dispatching of the Marines to Beirut to Obama's mini-surge of troops into Afghanistan – that he says accomplished none of America's envisioned objectives.

Professor Bacevich, author of "The Limits of Power: The End of American Exceptionalism," echoes average Americans' conclusion that Middle East interventions "haven't worked" when he says America's "military enterprises" in the Middle East have neither made the region more stable or more democratic, nor enhanced America's standing in the eyes of the Muslim world.

Thirty years after Reagan withdrew the Marines from Beirut after their barracks were bombed, and with memories of Iraq and Afghanistan (where 60,000 US troops remain) still fresh, Americans want a break – especially from military interventions in confounding civil wars.

But even Americans who have decided they no longer want the US to be the world's policeman aren't necessarily saying they want America to disengage from the world. The University of Maryland's Kull, coauthor of "Misreading the Public: The Myth of a New Isolationism," says one reason America's mood is labeled "isolationism" is that opinion polls generally offer the options of isolationism or interventionism, when in fact he says Americans want something else – a third way.

"There's a tendency to think about public opinion as moving along a linear scale, between yes or no, positive or negative, or in this case, isolationism or interventionism," Kull says. "But if you turn that line into a triangle, you get a different result."

Offer a trio of options – unilateral engagement, disengagement, and cooperative engagement with the world – and the allure of turning inward appears to be less strong.

A 2011 Gallup poll even offered Americans four options for what role America should play in the world – no role, a modest one, a major but not leading role, and a leading role – and half chose the "major but not leading role" option. Only 16 percent chose a leading role, while a scant 7 percent preferred no American role in world affairs.

"We're seeing people moving away from the dominant form of foreign engagement that they've experienced over the past decade or so because they see it as too unilateral," Kull says. "But they overwhelmingly choose a more cooperative form of engagement if given that option."

It may be a while before a president is able to summon a majority of Americans to support a military intervention in the Middle East, especially absent a strike at America's heart like the 9/11 attacks. But if the president can make the case that the world stands with him (or her) and that the action will be a cooperative international effort, then an intervention-shy America that's turned to tending its own garden may indeed rally to the cause.

More broadly, the public debate Obama said he wanted America to have on intervening in Syria may have told us something bigger about the direction of America's role in the world.

A turning inward so vividly revealed by the Syrian chemical weapons crisis and a president's call for intervention may yet prove to be a relatively short lived reaction to a decade of Middle East wars.

But if the American public's clear preference for "minding our own business" turns out to be part of a larger and more firmly rooted trend – like the crouch the country went into after the Vietnam War – it could have deep implications not just for foreign policy and America's projection of power, but also for domestic issues as varied as federal spending and immigration reform.

Over the course of the past month's debate, numerous members of Congress who trumpeted their opposition to intervention in Syria also made a point of cautioning other "rogue states" that they should not interpret congressional opposition as an American retreat. Iran and North Korea were put on notice. Still, the widespread recoiling from intervention suggests that projects to change regimes, spread democracy, stop genocide – even "modest" steps (as Obama said) to punish grave global wrongs – may be off America's agenda.

It was John Quincy Adams who said just shy of two centuries ago that, while America "is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all" in the world, "she goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy."

With the "American century" that followed America's lead role in destroying Europe's Nazi "monster," Adams's thinking might seem passé – even more so with the advent of globalization. It may be, however, that Americans are signaling a desire for a more modest role in the world.

• Contributing to this report were correspondents Carmen K. Sisson in Mobile, Ala., and Noelle Swan in Boston.