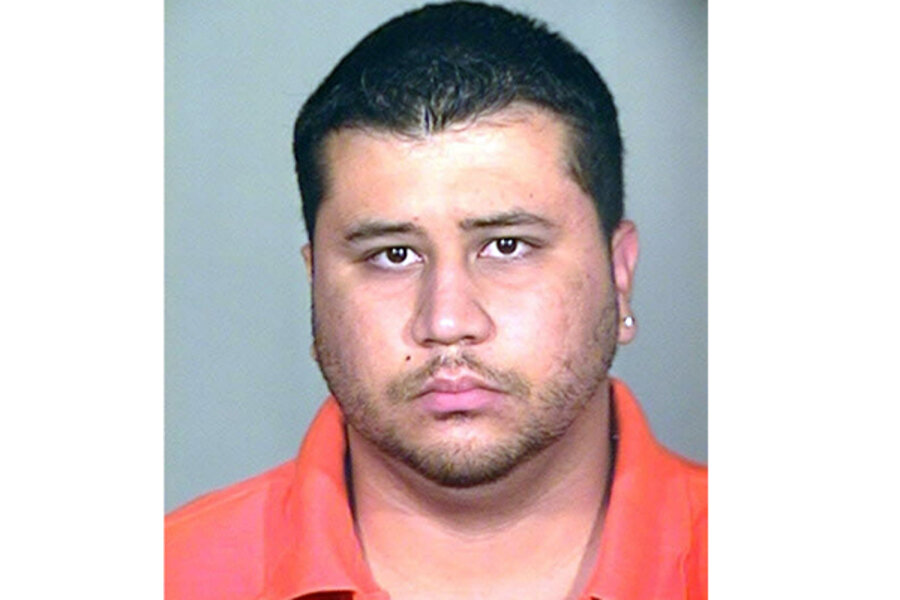

George Zimmerman 911 call: what the fallout is from botched editing

Loading...

| Los Angeles

The revelation that NBC News altered the recorded 911 call that George Zimmerman made to police before he fatally shot Trayvon Martin has brought down heavy criticism on NBC – and points up the dangers of a case being tried outside the legal system, say media and legal analysts.

“This guy looks like he’s up to no good.... He looks black,” is what the edited version of the tape presents Mr. Zimmerman as saying. It aired on the “Today” show last week. But it was edited in such a way that suggests Zimmerman was racially motivated. The actual conversation is: “This guy looks like he’s up to no good. Or he’s on drugs or something. It’s raining and he’s just walking around, looking about,” Zimmerman said.

The dispatcher asked, “OK, and this guy – is he black, white, or Hispanic?” Zimmerman replied, “He looks black.”

NBC has apologized for the editing and launched its own investigation into what happened. “During our investigation it became evident that there was an error made in the production process that we deeply regret,” says a statement released by NBC spokeswoman Lauren Kapp. “We will be taking the necessary steps to prevent this from happening in the future and apologize to our viewers.”

The full 911 recording doesn’t necessarily exonerate Zimmerman of any wrongdoing, media experts note. But they add that before conclusions can be reached, authorities need more time to carefully go through the details of the Trayvon Martin case.

“The NBC/‘Today’ show problem is just one example of the confusion and rush to judgment which has been at the forefront of this case,” says Richard Goedkoop, professor of communication at Philadelphia’s La Salle University, in an e-mail. “The larger problem here is that the news media as a whole and the punditry class, in large measure, feel that they need to analyze and ‘solve’ this case before the authorities have finished a full investigation.”

Professor Goedkoop adds, “It is time to give it time and to withhold our judgment, as difficult as that might be.”

Some media experts have taken direct aim at NBC.

“The incident serves as a reminder about some basics of journalism: check your facts, curb your preconceptions, and don't distort other people's words through selective editing,” says Jack Pitney, professor of government at Claremont McKenna College in California, in an e-mail. “The story undermines public confidence in the mainstream news media, which is already pretty low.”

In a recent Pew Research Center study, Professor Pitney notes, 77 percent of respondents perceived the press as lacking fairness. Seventy-two percent said the media were unwilling to admit mistakes, 66 percent cited inaccurate reporting, and 63 percent saw political bias.

Still, the potential legal case involving Zimmerman is not altered one whit, say legal analysts.

“Prosecution decisions are not made based on news clips; they’re made based on the evidence available to the prosecution, which undoubtedly included the original 911 recording,” says Caleb Mason, professor of law at Southwestern Law School in Los Angeles, in an e-mail. “If there’s a trial, it will be about what happened that night, as far as can be reconstructed from the recordings, eyewitnesses and forensics. Whether NBC got the story right or not means nothing for the trial.”

It isn’t unusual for a news organization to edit a tape, says Derede McAlpin, a vice president at Levick Strategic Communications.

“As quiet as it is kept, quite a few news organizations edit original content. It is a common practice,” she says by e-mail, adding, “It is also important to note that what you see in the media is not necessarily admitted in a court of law.”

Gordon Coonfield, professor of communication at Villanova University in Pennsylvania, sees parallels with the case of Rodney King, whose beating by Los Angeles police was videotaped. [Editor's note: The original version of this paragraph named the wrong professor.]

“The nation felt quite certain it saw the truth of what happened to Rodney King. The public is similarly sure about this case,” he writes in an e-mail. “The [district attorney] in King's case tried it as if the images spoke for themselves. Yet ... the defense won by offering a more convincing explanation of the images, focusing on what is by definition invisible – the officers' motives, reasoning, judgment, and feelings.”

He continues, “The [acquittal of the police officers resulted in] one of the worst riots in our nation's history. You have to wonder if we are doomed to repeat a history we refuse to learn from.”