Guantánamo trial boycott? Judge says defendants don't have to attend

Loading...

| Forte Meade, Md.

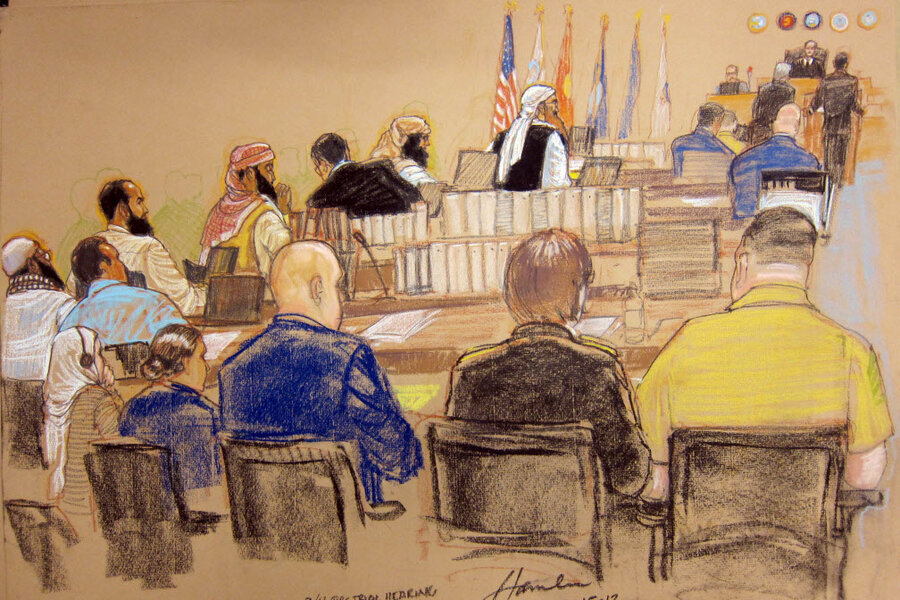

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and his four co-defendants in the 9/11 terror conspiracy trial are not required to attend future sessions of the special military commission at Guantánamo, a military judge ruled Monday, opening the door to a potential boycott of the proceedings.

The judge, US Army Col. James Pohl, said he would allow the accused 9/11 conspirators to choose not to attend future legal proceedings in the case.

But the judge stressed that the alleged Al Qaeda members must sign daily written waivers of their right to attend the commission sessions indicating that they fully understand the potential negative consequences of their absence from a terror trial that carries a potential death sentence.

“The accused can … choose to voluntarily not attend a session of the commission as long as he understands his right to be present and what his actions may or may not mean,” Pohl said.

When asked if he understood the negative consequences of any decision to avoid his trial and any resulting failure to consult closely with his defense counsel, Mr. Mohammed said he understood the risks.

“But I don’t think there is any justice in this court,” he added.

The directive takes effect Tuesday morning when each of the five defendants will be asked whether he wishes to attend the day’s legal proceeding.

The action came on the first of five days of hearings to examine 25 pretrial motions that must be resolved before the five defendants may be put on trial before a special military commission at the US Naval Base at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

Among pending issues is how classified information is to be protected during the trial, whether the defendants will be allowed to testify about their alleged torture while in CIA custody, to what extent the trial will comport with constitutional protections, and whether repeated and prominent public statements by Presidents Bush and Obama have made it impossible for the defendants to receive a fair trial.

In addition to the reporters covering the hearings in the courtroom at Guantánamo, other members of the media (including this correspondent) will monitor the proceedings by video at Fort Meade, Md.

Mohammed is accused of conceiving, planning, and directing the Sept. 11 attacks that killed nearly 3,000 people in 2001. The four others are accused of carrying out supporting roles that helped accomplish the alleged plot.

All five defendants face possible death sentences, if convicted.

In addition to Mohammed, the accused are Walid bin Attash, Ramzi bin Al-Shibh, Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, and Mustafa Al-Hawsawi.

A trial date has not yet been set.

At Monday’s hearing, Pohl questioned each of the five defendants about whether they understood their right not to attend the proceeding and whether they understood the potential detrimental consequences.

The judge provoked a confused response from several of the defendants when he sought to illustrate the full scope of their waiver to attend the trial. He asked if they understood that even if they were no longer in custody at Guantánamo, their trial would continue without their presence, including a possible conviction and sentence.

When asked this, Mr. Hawsawi paused and told the judge he did not understand.

The judge offered a hypothetical: “If for some reason you were able to escape and get out of military control – I’m not saying that will happen – but if you were to escape, do you understand that this trial would continue?”

Hawsawi mouthed the words: “Escaping from custody?”

“I’m not saying it is going to happen,” Pohl hastily replied. “But do you understand that the trial would continue?”

“Yes I do,” he answered.

When the judge asked the same question of Mr. Ali, he had a ready answer. “I’ll be sure to leave a note when I go,” he said.

The chief prosecutor in the case, US Army Brig. Gen. Mark Martins, had argued earlier in the hearing that the law establishing the Guantánamo commission, the Military Commission Act, and the underlying rules for the commission require that the defendants attend their military commission trial and pretrial hearings.

The rules would permit a defendant to miss a trial day for illness or other reasonable excuse, he noted, or if the judge determined that his behavior was disruptive. Other than that, Martins said, attendance is required.

Defense lawyers disagreed, noting that the underlying issue relates to the defendant’s right to be present during the trial. If that right belongs to the defendant, it is not up to the government to enforce it, they said.

“In this case our clients may believe, I don’t want to go to court, I don’t want to have anything to do with the court,” said James Harrington, defense counsel for Mr. bin al-Shibh.

Prior to his arraignment in May, co-defendant Mr. bin Attash refused to attend the proceeding. Guards strapped him to a special restraint chair and carried him, against his will, into the courtroom.

A defendant in a terror trial in New York, Ahmed Ghailani, boycotted a portion of his trial because he objected to having to undergo repeated strip and body cavity searches on his way to and from court.

On Saturday, Ali’s lawyer, James Connell, filed an emergency motion to allow his client to avoid appearing in court Monday. Mr. Connell said Ali had recently learned that his father had died in Kuwait and he is in mourning.

The motion was apparently denied. Ali was present in court on Monday. But now there is a process in place that would allow him, if he chooses, to remain in his cell rather than attend the Tuesday’s hearing.

Pretrial hearings are expected to continue Tuesday morning.