Jailed without conviction: Behind bars for lack of money

Loading...

| New Orleans

The teenager opened her neighbor's unlocked car, grabbed the iPhone off the armrest and ran home, a few doors away in her downtown neighborhood here.

Perchelle Richardson still isn't sure why she took the phone. Just five days earlier, for her 18th birthday, her mother had given her a standard, no-frills cellphone. But she loved the way iPhones looked, and her little brothers had seen this one through the car window as they played outside.

The high school student, with no previous criminal record, was arrested and, because her family couldn't raise the $200 to spring her, would spend 51 days in jail, missing school, before she got her day in court. Her public defenders unsuccessfully asked the judge to release her without court fee and after that could do little beyond bringing her school worksheets, which she craved, she says, because they helped to break her boredom.

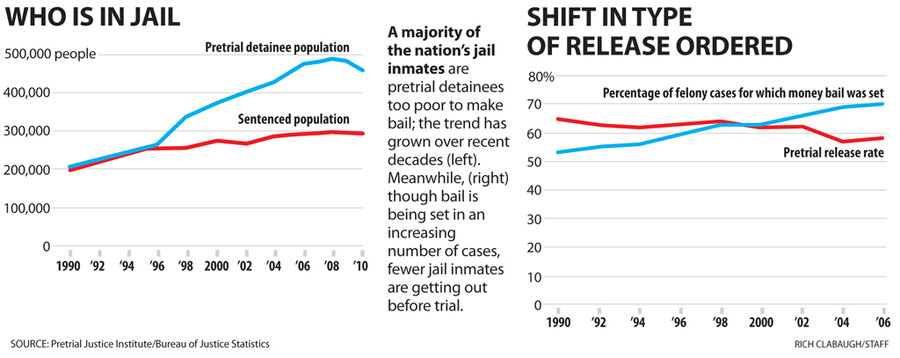

Ms. Richardson is symbolic of a little-known criminal-justice crisis that affects the millions of low-income Americans each year who languish behind bars in city and county jails. On any given day, three-quarters of a million people are jail inmates and two-thirds of them haven't been convicted of anything, according to US Department of Justice statistics. They are awaiting trial, and an estimated 80 percent of them cannot afford to pay bail.

Most won't go to prison: Overall, 95 percent of those booked into local jails in 2010-11 were not subsequently sent to prison, says Timothy Murray of the Pretrial Justice Institute (PJI). And 75 percent of felony defendants will be judged innocent, given probation, or sent to rehabilitation programs and never end up being sentenced to prison, says longtime correctional researcher James Austin.

Richardson's stay would have been longer, but an aunt helped the family put together the court fee. She was released two weeks before she was arraigned in court.

Many defendants, like Richardson, serve more time waiting for trial than the sentence they receive for their charges – particularly for petty or probation-worthy offenses. Yet in New Orleans, like other cities across the nation, there are countless stories about how the lives of poor people were set back while they sat in jail, all for the lack of a relatively small sum of money. There's the dishwasher stopped on a traffic-ticket warrant who lost his job while waiting for trial; the jailed fast-food worker who couldn't reach her landlord, was evicted, and lost her possessions, which were stacked on the curb.

"Every case of unnecessary pretrial incarceration is much more than simply an effective and unjustifiable waste of taxpayer money – it has direct and tragic human costs," says Judge Truman Morrison III, who has sat on the Washington, D.C., Superior Court bench for 30 years and is PJI's board chairman. Judge Morrison says that even though courts have in recent decades developed pretrial programs in which most defendants return to court without problem, the ways that the justice system sets bail haven't changed. "Most judges spend their days saying, '$200, $500, $1,000.' They have no idea if these people are getting out," he says.

And for the local jurisdictions who pay for those jail beds, needless pretrial incarceration costs billions each year, according to Justice Department estimates.

Bad food, insect bites, and missed school

As soon as Richardson held the new iPhone in her hands, she had mixed feelings, she recalls. She felt guilty about taking it from her neighbor, whom she saw every day. She remembered hearing that stolen iPhones are simple to track, so she feared being caught. As she stood in her house debating what to do next, two police officers came to her door. She handed them the phone. They handcuffed her and took her to central lockup.

Richardson was booked for felony burglary because the iPhone she'd taken was the newest version, with 32 gigabytes of memory, which put it over the $250 misdemeanor ceiling.

That evening, a magistrate judge set her bond, a $5,000 personal surety that allowed her to be released with the signature of a trusted person who pledged to pay the bond's value if she didn't return to court. Legally, that's the reason judges set bond: to ensure that defendants return to court to face their charges.

Richardson remembers the judge summarizing the surety concept, saying that her older sister could simply come "sign her out" in the morning. But in New Orleans, surety bonds carry a $200 administrative fee. And Richardson's family couldn't afford that. So her sister came in the morning, but left without her.

Days turned into weeks. This familiar wait is known to New Orleans inmates as "D.A. time," because state district attorneys have 60 days to decide whether to pursue a case.

"I thought they had forgot about me," Richardson says, noting that the empty days were more difficult because of constant stomach upset that she attributes to the jail food and because of insect bites that covered her body for part of the time. She regularly begged deputies to see whether a court date had been scheduled, but they could offer nothing. Her sense of isolation was compounded because her mother couldn't afford to purchase a prepaid phone card for her: "I didn't talk to my mama at all."

As the days mounted, Richardson – still a high school sophomore because she'd fallen behind after transferring schools nearly a dozen times in the wake of hurricane Katrina – missed crucial end-of-the-year school time. She would discover later that her family had moved while she was in jail. Without Richardson's help baby-sitting her three younger brothers and toddler niece, her sister (a waitress) and her mother (who cleans antiques in a French Quarter store) had scrambled to find someone to watch the kids when they went to work. So they moved closer to an aunt who could baby-sit.

In the end, Richardson was never convicted. Instead, she was assigned to a diversion program, which required her to periodically check in with court staff for a few months. Then the district attorney halted prosecution, leaving her without a conviction on her record.

Richardson's 51-day jail stay cost the city of New Orleans $1,142, part of the $10 million it pays each year to hold pretrial defendants, who occupy roughly half of the jail's beds.

Bail guarantees return, not safety

Certainly, there's reason to hold a suspected lawbreaker in jail – some inmates are held because they pose a danger to others. But, says Shima Baradaran, an associate professor at Brigham Young University Law School, that's the exception, not the rule: "The overwhelming majority of people in our nation's jails are not a threat to society. Most are detained for minor offenses and simply did not have the money to get out of jail."

Bail is the money needed to obtain release pretrial, as determined by a judge. The legal purpose for bail is to assure that a defendant will return to court.

Of those detained in jails in the United States, three-quarters face nonviolent charges, for drug, property, or petty offenses, says Ms. Baradaran, who chairs the American Bar Association's Pretrial Release Task Force. She and Rutgers Business School economist Frank McIntyre culled 15 years of felony data from the largest counties in the US. They found that only 1 to 2 percent of felons are rearrested for a violent crime before trial.

They concluded that there would be no increase in crime if courts released 25 percent more people without one bit of additional supervision, Baradaran says, noting that an even larger number could be released under expanded pretrial programs.

Mr. Austin, of the JFA Institute, a criminal-justice research organization in Washington, D.C., also questions the use of costly jail beds to hold large numbers of pretrial defendants because, in the 1980s, his research found that court supervision could improve outcomes of pretrial release programs.

The use of bonds has increased sharply in recent decades. Judges set money bonds in 53 percent of felony cases in 1990. By 2006, that figure had risen to 70 percent. The proportion of jailed pretrial defendants also rose during that time, presumably because release became unaffordable for many.

Bail-only release is not the only way

Last year, US Attorney General Eric Holder decried the proportion of jail inmates held pretrial on bonds beyond their means: "The reality is that it doesn't have to be this way.... Almost all of these individuals could be released and supervised in their communities ... without endangering their fellow citizens or fleeing from justice."

Mr. Holder and his colleagues have been proponents of "pretrial services programs." The appeal of the programs is that they can address both public safety and overdetention by moving away from the bail-only system.

Cliff Keenan, who runs the pretrial services program in Washington, D.C., states the position most succinctly: "Money should not control. Dangerous people get out of jail, and people who are not dangerous, but don't have the money, stay in jail."

Most large cities now have a pretrial services agency that interviews and screens defendants shortly after arrest, red-flagging anyone who poses a risk of fleeing or reoffending. But some pretrial services programs barely make a dent in pretrial detention, some because of ineffectiveness, others because of opposition by bail bondsmen coupled with reluctance of justice officials sensitive to looking weak on crime.

Typically, those who pose low or little risk are released on their own recognizance. Defendants who pose the most risk are held without bail or – often – given a very high bond, which judges hope defendants won't be able to pay.

Those arraigned who pose a moderate risk are released but monitored by pretrial services staff, through ankle bracelets, regular check-ins, or drug screens. A court-reminder program also calls defendants as their court dates approach, a method shown to reduce no-shows.

The proportion of defendants released without bail before trial varies wildly between jurisdictions. Harris County, in the Houston area, releases only about 5 percent of defendants without bail. But across the state in the capital, Austin, judges typically release more than 60 percent of defendants without requiring them to post bail. Even within Kentucky, which established a statewide pretrial services agency more than 30 years ago, county release rates range from 20 to 97 percent.

Thanks to its longstanding pretrial services program, Washington, D.C., has one of the highest rates of pretrial release – 85 percent. That's a point of pride for Mr. Morrison of the District of Columbia Superior Court: "There is nobody in our jail tonight simply because they cannot pay their money bail."

Supervision at the 'grandmother level'

Bail bondsmen argue that they are the best time-tested way to ensure a defendant's return to court. Dennis Bartlett, the head of their industry association, the American Bail Coalition, says bail was the first-known risk-assessment tool and paraphrases the Old Testament book of Proverbs: "He who goes bail for a stranger will rue it."

The bail-bond industry – which dwarfs the pretrial community in terms of employees and reach – has historically taken on the risk of helping people receive their constitutional right to release, Mr. Bartlett says. Without any cost to taxpayers, bail bondsmen arrange for the release of nearly 4 million people out of the nearly 13 million arrests each year, he says. And, he adds, nearly everyone – 97 to 98 percent – returns to court to face charges. If the return rate didn't stay that high, bail bondsmen couldn't stay in business, he notes.

Bartlett says that he believes that pretrial services have a place in the justice system for helping those who are mentally ill or indigent.

But to limit services to that subset of inmates would still leave too many detained for too long, argues Mr. Murray, of PJI, which was founded by the US Department of Justice in 1976. Murray acknowledges that many commercial bondsmen have ties to families and a long history in most cities and their courthouses. "We have relied on a cash-based system for years," Murray says. "Practitioners have an underlying faith and belief that it works, and works effectively."

Still, Murray contends that the current bail system should be reformed. His perspective wins over officials, he says, because it's not "profit driven" and because his programs use refined, research-based tools for assessing risk rather than what he views as a more crude instrument, cash for freedom.

But bail bondsmen who have done this work for years bristle at the term "for-profit bail," often used by those who oppose the current system. "We're working hard every day," says New Orleans bail bondsman Blair Boutte, describing how he answers his phone 24 hours a day and how his three brothers track down anyone who doesn't show for court. "That's what a bail bondsman is supposed to do," he says, contrasting his work with that of pretrial services programs, which rely upon local law enforcement to find fugitives, he says.

Bartlett says that, in place of court-prescribed ankle bracelets or telephone monitors, his industry is able to maintain a "social control" over defendants from the very moment a family member posts bail for them, he says.

And when pretrial services programs add supervisory elements – typically calls and drug tests of pretrial defendants – Bartlett wonders whether that infringes on the rights of defendants who should be presumed innocent.

He says that his bail agents rely upon their community ties to fulfill the defendant's only true obligation: to appear in court at a certain time. To make that happen, he quips, "Supervision is done at the grandmother level."

Reform that can save public expense

Jail costs have increased more than 500 percent during the past 30 years, according to US Department of Justice data. And most jails are paid for by cities and counties, which are struggling to balance budgets and have – as a result – expressed increasing interest in pretrial service programs, says Murray.

Currently, about 300 pretrial service agencies exist, serving roughly 1,000 of this country's 3,000-plus counties. But that number will probably grow, because the National Association of Counties recently threw its support behind the idea of pretrial detention reform, joining a list of nearly a dozen national organizations representing police chiefs, probation and parole officers, jailers, sheriffs, prosecutors, criminal-defense attorneys, and legal aid lawyers.

Tara Klute, a national consultant on pretrial justice issues, says she also sees momentum as new agencies launch and others expand. She understands the motivations of county officials because she's spent 17 years heading the statewide Kentucky Department of Pretrial Services, which covers 120 counties. Often, Ms. Klute says, she hears from counties elsewhere hoping to trim jail budgets. "[O]nce they see the concept of pretrial, it's a pretty easy sell."

In the District of Columbia, Police Chief Cathy Lanier is considered one of the "staunchest supporters" of pretrial services. In speeches, she has emphasized that a strong pretrial services system helps the district strategically focus its law enforcement resources on the "roughly 5 to 6 percent" of violent, dangerous repeat offenders who create "80 percent" of the problems.

Morrison, the Washington judge, traces the growing interest in "pretrial justice" to increased attention from researchers. But he's cautiously optimistic. Washington courts have operated pretrial services since the 1960s, so his colleagues are used to the program, he says, while in other places, his judicial peers may view such a new agency as a challenge. After all, adds the judge, his "is the only line of work where I, inexorably, have the last word."

Bail is not supposed to be punishment

Klute presides over a pretrial system considered a success story. The state of Kentucky established statewide pretrial services in 1976 and is one of only four states without commercial bail. Today, Kentucky counties release an average of 76 percent of defendants on nonfinancial bonds, a rate that has risen recently because of a 2011 state law that requires judges to consider pretrial services' risk assessment when making release decisions.

As a result, in some Kentucky counties, only 3 percent of defendants must put up money for release. To an outsider, there is no rhyme or reason to the rates by county – some require up to 80 percent of defendants to put up money.

Some critics say that judges in Kentucky and beyond set bonds because they're corrupt or tied too closely to longtime bondsmen, who finance campaigns. Klute says it's more complicated, that release rates reflect "the culture in individual counties."

Morrison says that in some places, bail is seen as punishment. He cites an example of a judge who says, "It looks like the message hasn't gotten through to you, Ralph," and then sets a $50,000 bond, with hopes that Ralph will stop stealing from Wal-Mart.

Many in the general public believe that anyone arrested should pay bail as a sort of penance. But, says Morrison, that's "an absolutely impermissible use of bail," unsupported by law.

In some places, judges' caution can be explained.

For example, at first glance it may seem as though an adherence to tradition reigns in Harris County, Texas, where magistrates release only about 5 percent of people on the nonfinancial personal signature of a third party. But judicial observers say that there was a time when release rates were higher in the Houston area. They trace the start of a decline in release rates to an ad campaign financed a decade ago by a conservative lobbyist group. Full-page newspaper ads showed photos of defendants who'd been given bail, with headlines such as "Your Tax Dollars Released This Person."

Carol Oeller, who has headed Harris County Pretrial Services for 13 years and worked in the field for 33 years, still believes that she's providing a crucial service. Judges trust her agency's supervision and rely on the information her agency provides to make their bonding decisions, even though they follow it only 30 percent of the time, she says.

Most people see common sense on both sides of the issue, Ms. Oeller says, recalling how she had heard a bail bondsman say that if someone is willing to pay him to release an inmate, it's an indicator of lower risk. "It makes intuitive sense," she says. And she has overheard others talk about public safety and how dangerous inmates shouldn't be able to buy their way out of jail. "And people will say, 'Yeah, you're right.' "

Pretrial services help judges assess risk

In New Orleans, where a pretrial services program began last spring, the operative posture seems to be one of caution.

The biggest worry for any judge is that he or she will release someone out on the street who will reoffend or turn violent. Those cases can haunt a judge: the armed robber who's released and shoots his next victim, the mentally ill defendant who goes home and kills his mother.

To date, no one has held a press conference decrying a judge because he did not release a defendant who posed no risk to the public.

Chief Magistrate Judge Gerard Hansen, who's presided on the Orleans Parish Court for 38 years, says that he's grateful for the additional information he gets from the Vera Institute of Justice, the justice policy nonprofit that runs the new pretrial services program for his court.

The district attorney has for years provided the magistrate with criminal records of defendants, he says. "But unless I asked the defendant directly, I didn't have any information about employment, stability, and mental health or whether he was living with family or children," Judge Hansen says. He wasn't able – as Vera staff is – to get reliable, independently confirmed employment and family situation information before the magistrate hearing, he says.

Recently, Vera began screening defendants for diversion programs right away. If that had been in place earlier this year, Richardson might have been released immediately, with orders to check in the next day at the district attorney's office.

Still, there are times, Hansen says, when Vera's staff will tell him that someone ranks, say, a 7 as a risk for release, but he believes that they pose a higher risk, maybe closer to an 11. At that point, he defers to himself.

"I'll follow my instincts," Hansen says. "I've been doing it longer. And I've been living here longer."

• The editor of this article received a fellowship – involving paid travel to New Orleans and a two-day course on the topic of pretrial reform – sponsored by the Center on Media,Crime & Justice at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice.