'Piracy' at sea: Has definition changed? Supreme Court declines to enter fray.

The US Supreme Court on Tuesday let stand a series of lower-court opinions endorsing a broad view of what constitutes the crime of piracy – a move that will make it significantly easier for the government to prosecute and convict suspected Somali pirates in federal court.

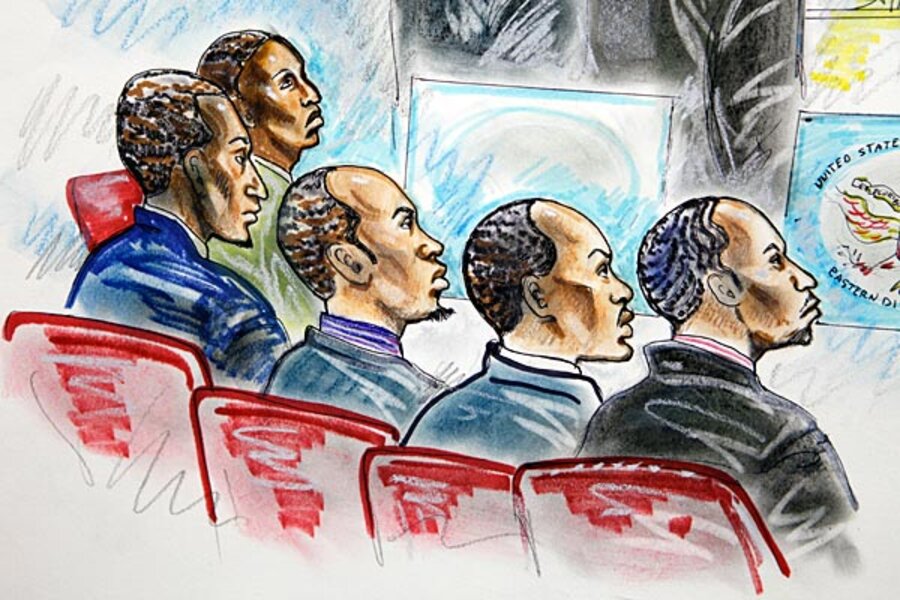

The high court turned aside an appeal by five Somali nationals convicted of firing shots from a small skiff at a US Navy frigate on patrol 600 miles off the coast of Somalia on April 1, 2010.

The warship, the USS Nicholas, returned fire and sank the boat. Three men were taken prisoner. Two others were captured on another small boat nearby.

The action was part of an international response to widespread violence against cargo ships off the coast of Somalia. The alleged pirates would fire upon and board civilian ships and then hold the ship, cargo, and crew hostage until hefty ransoms were paid.

The Somalis are said to have mistaken the warship for a commercial vessel.

All five prisoners were brought to the United States and charged with piracy. They were subsequently convicted and sentenced to mandatory terms of life in prison on the piracy charge, plus 80 years for firearms and other violations.

On appeal, defense lawyers argued that their clients’ encounter with the US warship did not amount to piracy. The historic definition of piracy was robbery at sea, they said. Since their clients never forcibly boarded the warship or removed anything of value from it, they could not be prosecuted for robbery at sea.

Federal prosecutors countered that the definition of piracy had broadened since Congress passed the piracy statute in 1819. Under international law, they said, piracy includes a wider range of hostile acts.

A federal judge agreed, and that ruling was upheld by the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond, Va.

A second group of five Somali nationals raised the same issue before their federal trial on piracy charges.

The second group allegedly fired a shot from a skiff at the USS Ashland on April 10, 2010, while the warship was on patrol in the Gulf of Aden.

The US warship returned fire, sank the skiff, and took all five Somali nationals into custody. Like the others, they were taken to the US to stand trial on piracy charges.

The federal judge presiding over that case ruled in the Somalis’ favor, dismissing the piracy charge against the men.

On appeal, the Fourth Circuit overturned the federal judge, citing its ruling in the USS Nicholas case.

Lawyers for both groups of Somalis urged the Supreme Court to consider whether the Fourth Circuit was correct in permitting judges to embrace a broad definition of “piracy” that exceeds Congress’s 1819 definition of “robbery at sea.”

The justices rejected both appeals without comment.

“Mere firing of a weapon at a ship does not constitute piracy for purposes of the Piracy Statute,” lawyers for the Somalis argued in their brief to the court.

Government prosecutors countered that the piracy statute was not limited to robbery at sea, but embraced a wide range of modern developments in international law.

Geremy Kamens, assistant federal public defender, said his clients face a draconian punishment of mandatory life in prison if convicted of piracy. But, he added, the case raised a more fundamental issue: whether US judges have the power to define elements of a federal crime based on their view of the state of modern international law.

“Under the Constitution’s separation of powers, federal courts lack authority to make laws,” Mr. Kamens wrote.

If the justices allowed the Fourth Circuit opinion to stand, he warned, it would “pave the way for judges to legislate based on evolving standards – even if those standards did not exist at the time the criminal offense was enacted.”

James Theuer, a Norfolk, Va., lawyer representing the group of Somalis already convicted, wrote in his brief that the Fourth Circuit decision undercuts nearly 200 years of jurisprudence supporting a narrow reading of the piracy statute.

The cases are Dire v. US (12-6529) and Said v. US (12-6576).